With the growing appetite for emerging market debt and in the hunt for better yields, Indonesian sovereign bonds have been popular this year. The strong rally has continued since the first quarter (see a previous piece here). The S&P Indonesia Sovereign Bond Index, which seeks to track the local currency denominated sovereign bonds, jumped 15.24% YTD as of Dec. 7, 2017.

There were three new issuances added to the S&P Indonesia Sovereign Bond Index this year, with a total of INR 39 trillion. The total local currency new issuances in the index was only around one-third of last year’s rate, as Indonesian sovereigns continued to tap into different foreign currency markets; for example, they raised USD 4 billion from its global bond issuance in the first week of December. Meanwhile, the new issuances also extended Indonesia’s yield curve to 30 years.

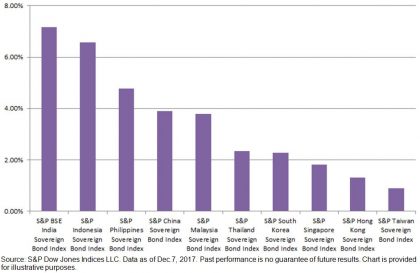

The yield-to-maturity of Indonesian sovereign bonds continued to trend lower. Throughout the year, it has tightened 131 bps to 6.57% (see Exhibit 1). It also represented a 312 bps plunge from the recent high, which was 9.69% on Sept. 30, 2015. Nevertheless, the yield is still competitive with its investment-grade rating of ‘BBB-’/‘Baa3’ and particularly compared to other Asian countries like India (at 7.17%, as represented by the S&P BSE India Bond Index with a rating of ‘BBB-’/‘Baa2’; see Exhibit 2).

The overall local currency bond market in Indonesia, as represented by the S&P Indonesia Bond Index, rose 14.05% YTD, and it was the best-performing country within Pan Asian bond universe.

Exhibit 1: Yield-to-Maturity of the S&P Indonesia Sovereign Bond Index

Exhibit 2: Yield-to-Maturity Comparison of the S&P Pan Asia Sovereign Bond Subindices