In the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2007-2008, one noticeable trend in fixed income investment is the growth and popularity of unconstrained bond funds. They have generated strong interest in the investment industry due to the flexibility they offer in duration management and the broader investment universe. Because they are not managed against a specific benchmark, unconstrained bond funds may also pose challenges for investors in understanding and measuring their performance.

The global financial crisis of 2007-2008 and the economic recession that followed prompted unprecedented quantitative easing monetary policies across many countries. Not only were short-term interest rates lowered to either zero or close to zero, but quantitative easing was also adopted in places such as the U.S., the U.K., the eurozone, and Japan to flatten the yield curve and keep long-term interest rates low. As the U.S. economy continues to recover and the Fed starts to increase interest rates, many investors have concerns about holding core fixed income products with high interest-rate risk in a rising-rate environment. It is this widespread market sentiment that has driven the surging popularity of unconstrained bond funds, which offer wide latitude to fund managers on duration management and investment selection.

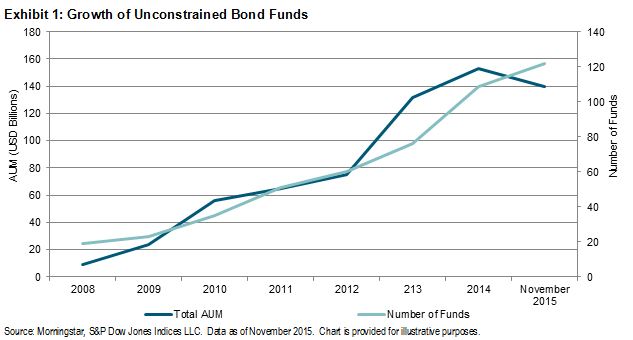

We use fund data from Morningstar to gauge the size and growth of unconstrained bond funds. In particular, we screen for funds categorized as “U.S. OE Nontraditional Bonds” by Morningstar, while excluding those with mandates in specific sectors or with duration constraints.

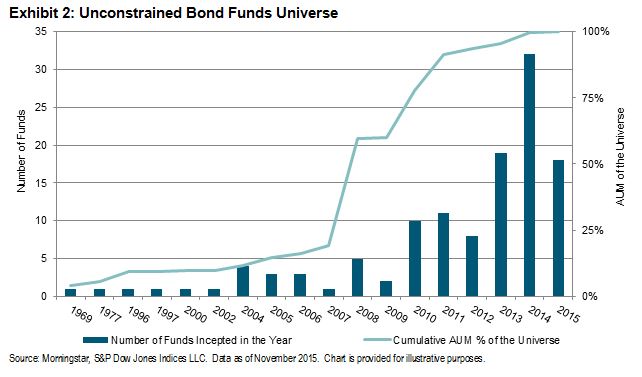

As of November 2015, there were 122 open-ended mutual funds with total assets under management (AUM) of USD 140 billion in our data set, in comparison with 19 funds with AUM of USD 9 billion at the end of 2008 (see Exhibit 1). Even though the first fund started in 1969, it wasn’t until after the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 that unconstrained bond funds started gaining traction among investors. Exhibits 1 and 2 show the rapid growth of unconstrained bond funds since 2008 in terms of both AUM and number of funds.