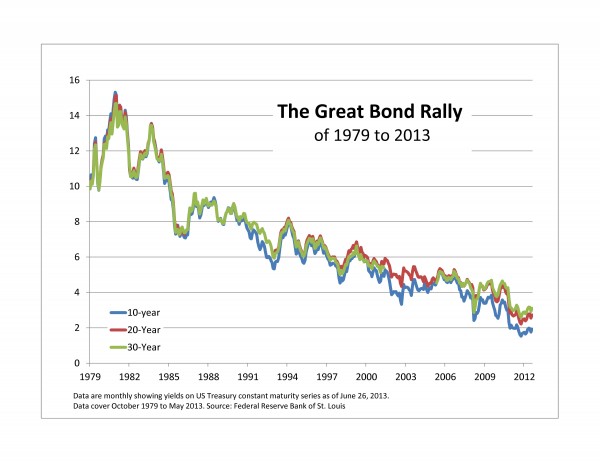

The markets and the pundits are calling for an upturn in interest rates and announcing the end of the Great Bond Rally. Rather than lamenting the end of low interest artes, it is worth looking back at how we got here to consider the prospects going forward. The bond rally goes back decades to inflation rates and yields that sound impossible today. In the late 1970s inflation was well into double digits at 12% to 15%. Though interest rates were rising, they were not quite keeping up with inflation so the real (inflation adjusted) cost of money was low and investors rushed to buy houses and hard assets. Despite repeated government efforts, inflation — and the damage it wrought on the economy — seemed unstoppable. Paul Volcker, the newly appointed Fed chairman, led a sharp shift in Fed policy in October, 1979 which drove interest rates sky high, sent the economy into two back-to-back recessions and knocked inflation out. Inflation dropped from 14.8% in March, 1980 to 2.6% in June, 1983. The bank prime rate — the analogy to Libor today — peaked at 21% and in November of 1981 the Treasury sold 30 year bonds with a 14% coupon which out-performed the S&P 500 the next year as bond yields collapsed So much for ancient history.

The turmoil in 1979-81 whipped inflation and sparked the bond rally that either ended last week or, hopefully, is still with us. The chart shows how long it has run and how far yields have dropped — from 14% to 2%. The legacy the rally is more than last week’s low yields; it is the almost complete absence of inflation. Unlike the 1970s and early 1980s, investors don’t have to constantly worry about inflation eating into their wealth or pushing bonds yields up and bond prices down. The result is a fixed income market that responds to monetary policy and credit conditions, allowing investors to both gauge the attractiveness and hopefully profit from different fixed income assest classes. Who would look at municipal bonds were inflation at 8%, 10% or 12%. There is no guarantee that inflation will remain low into the future, but if investors recognize the benefits of keeping price increases in control, the odds are that the Fed and others will hold inflation in check.

The Great Bond rally may, or may not, be fading, but its legacy of low inflation is with us to the benefit of fixed income investing.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.