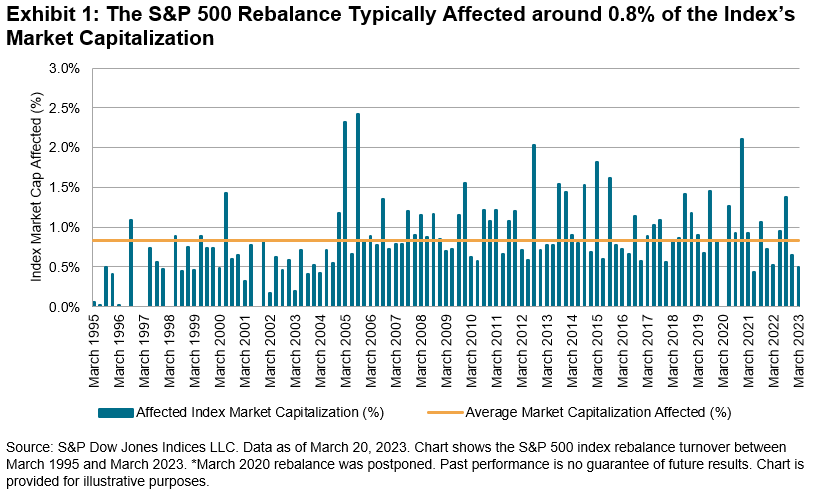

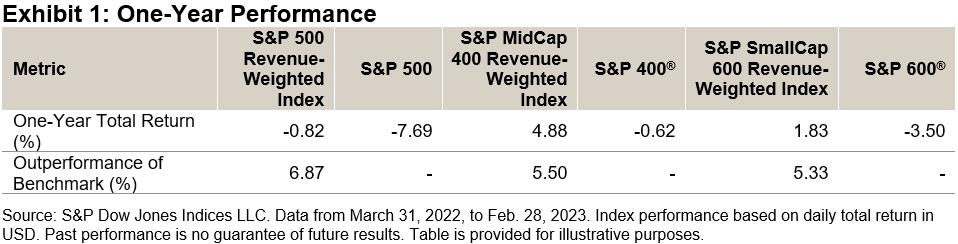

As persistently high inflation, high interest rates and geopolitical risks continue to dominate the macro environment, the S&P 500® Revenue-Weighted Index, S&P MidCap 400® Revenue-Weighted Index and S&P SmallCap® 600 Revenue-Weighted Index have outperformed their corresponding float-adjusted market-capitalization (FMC) weighted indices by more than 5% during the past one-year period (see Exhibit 1). In this blog, we will analyze the revenue-weighted index methodology, the short- and long- term performance, style tilts and sector composition.

Methodology Overview

As alternatives to the FMC-weighted indices, the S&P 500, S&P MidCap 400 and S&P SmallCap 600 Revenue-Weighted Indices are weighted by constituents’ revenues from the past four quarters. In order to provide broader coverage and reduce concentration risk, individual constituents’ weights are capped at 5%. Lastly, these indices are rebalanced quarterly in March, June, September and December.

The revenue-based index may be a better reflection of the broader economy, as revenue is directly tied to economic activity. Moreover, revenue is a direct indicator of a company’s ability to generate income and is less susceptible to accounting manipulations.

Short- and Long-Term Outperformance

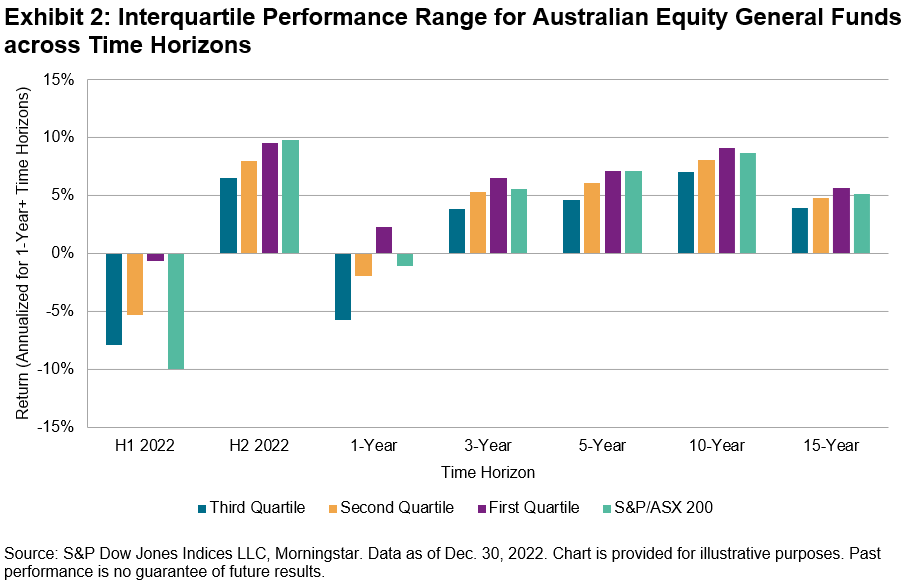

Historically, the revenue-weighted indices outperformed their corresponding FMC-weighted indices for all periods studied, in the short and long term, in terms of both total returns and risk-adjusted returns (see Exhibit 2).

Factor Exposure

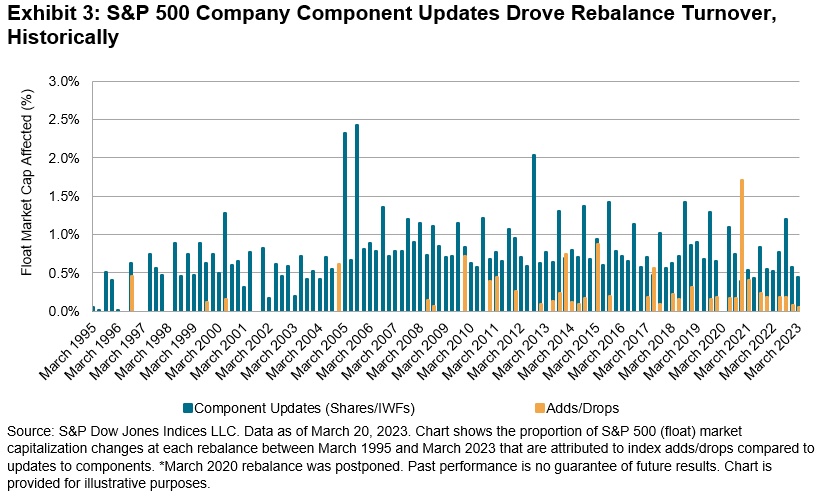

In Exhibit 3, the revenue-weighted indices demonstrated a value tilt versus their respective benchmarks. In terms of Axioma Risk Model Factor Z-scores, the revenue-weighted indices had higher exposure to the book-to-price ratio, comparable exposure to earnings yield and lower exposure to growth factors. The value tilt has proved beneficial in the recent rising interest rate environment. Holding all else equal, value stocks offered relatively more protection in a rising interest rate environment compared with growth stocks, due to their lower durations.

Furthermore, all three revenue-weighted indices showed comparable or slightly higher profitability, lower momentum and smaller size tilt than their corresponding FMC-weighted indices.

Sector Composition

Exhibit 4 shows the historic sector exposure difference between the revenue-weighted indices versus their benchmarks. The revenue-weighted indices overweighted Consumer Discretionary, Consumer Staples and Industrials, while having an underweight in Financials, Information Technology and Health Care.

Conclusion

Weighted by constituents’ revenues over the previous four quarters, the S&P 500 Revenue-Weighted Index, S&P MidCap 400 Revenue-Weighted Index and S&P SmallCap 600 Revenue-Weighted Index have historically provided consistent total returns and risk-adjusted outperformance over both short- and long-term periods. The revenue-weighted indices also showed value tilt in comparison with their corresponding benchmarks.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.