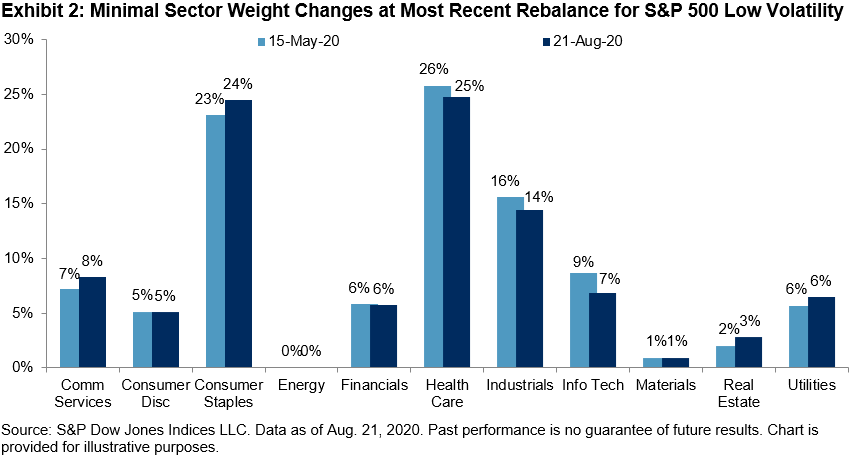

In recent days the S&P 500 reached multiple new highs, despite the still-uncertain nature of the economy’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Year to date through Aug. 20, 2020, the S&P 500 is up 6% while the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index is down 6%.

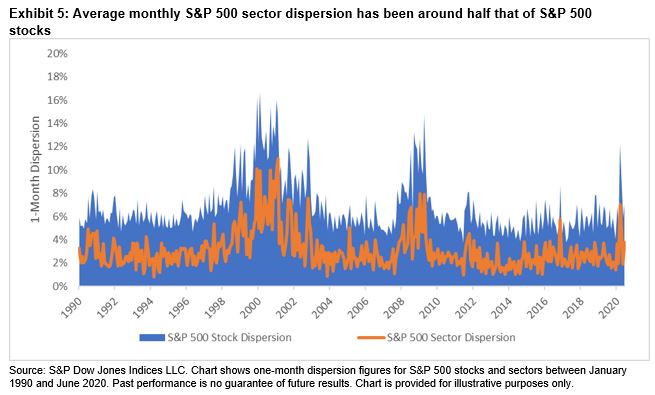

Market volatility remains high, as evidenced by the charts in Exhibit 1. In all sectors of the S&P 500, volatility spiked in March and, though it has leveled off, remains above average. Similar to three months ago, Energy and Financials were among the sectors with the greatest volatility increase.

It’s not surprising to see that there were only minute shifts in sector allocations for the latest rebalance in the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index (effective after market close Aug. 21). With just 11 names cycling through the index, turnover was well below average. Weights in Energy and Financials continue to be depressed relative to the S&P 500. Notably, since the rebalance in May, Technology has had a higher weighting than Utilities, an occurrence that has only happened once, very briefly, since 1991. It seems the new regime that caused big sector shifts in the previous rebalance is, at the moment, here to stay.

As a brief review, index modifications to the

As a brief review, index modifications to the