The South African economy, Africa’s second-largest economy after Nigeria, may be helped by reforms put in place by President Cyril Ramaphosa. Earlier this year, South Africa suffered a setback, as data showed the economy dipping into a recession, but Ramophosa has since unveiled a stimulus and recovery plan to try and get it back on track. The stimulus package encouraged investors by giving more certainty on mining and visa rules and by emphasizing skill development and education.

As the debate continues, the IMF has publicly stated, “Some of the initial optimism has dissipated as growth remains stuck in low gear and reform implementation has faced constraints.”[1]

Concerns over the economy tend to push local investors to the most secure investments and entice international investors to attractive yields. The performance of the South African sovereign market can be quickly reviewed with the S&P South Africa Sovereign Bond 1+ Year Index, which seeks to track the performance of local currency-denominated sovereign debt publicly issued by the government of South Africa in its domestic market, with maturities of one year or more.

Year-to-date, the index returned 5.55% as of Nov. 16, 2018. As mentioned above, the index history shows that, as the South African economy suffered a setback, risk-off trading led to an increased demand for sovereign bonds, and the yield to worst of the index reached a low of 8.29% on March 27, 2018. Since March, yields have increased and are currently ranging between 9.4% and 9.8% (see Exhibit 1).

Looking at the structure of the index, the universe of bonds currently includes 14 securities, with a market value of ZAR 1.4 trillion. The duration of the index is 7.2 years, with 9 of the 14 securities having a duration greater than the aggregate level.

The 2-year sovereign South African bond (7.25% on Jan. 15, 2020) began the year with a weight of 4.4% in the index but currently only holds 2%, as longer issues have increased in weight. As seen in Exhibit 2, the yield of the 2-year sovereign bond has tightened, while the 5-, 10-, and 30-year sovereign bonds have moved laterally. Since the beginning of September 2018, the 2-year sovereign bond bid yield has gone from a YTD high of 7.88% to 6.35%.

Some investors are skittish, as Africa’s most industrialized economy struggles with rising debt, though the government is working hard to improve the investment climate for both domestic and international investors, according to the minister of trade and industry.

For more information on the S&P South Africa Sovereign Bond Index and the S&P South Africa Inflation-Linked Bond Index, please go to www.spdji.com or follow these links.

S&P South Africa Sovereign Bond Index

S&P South Africa Sovereign Bond 1+ Year Index

S&P South Africa Sovereign Inflation-Linked Bond Index

S&P South Africa Sovereign Inflation-Linked Bond 1+ Year Index

[1] Toyana, Mfuneko. “IMF says optimism in South Africa’s economic recovery fading.” Reuters. Nov. 19, 2018.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

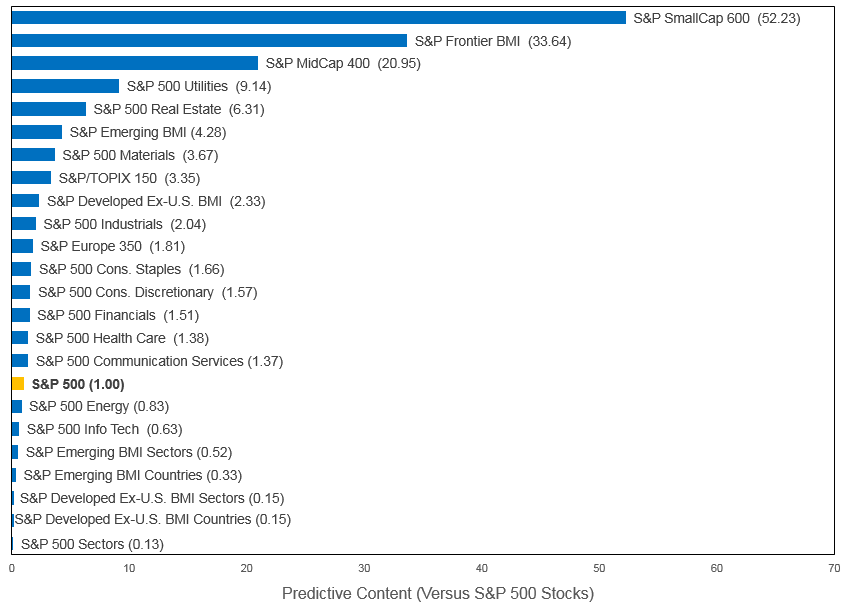

Low volatility’s success was not unique to the U.S. Exhibits 3 and 4 show that similar trends occurred globally, particularly in the emerging markets and Asia, regions that have experienced turmoil for most of this year. The

Low volatility’s success was not unique to the U.S. Exhibits 3 and 4 show that similar trends occurred globally, particularly in the emerging markets and Asia, regions that have experienced turmoil for most of this year. The

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source: