For decades, sophisticated institutional investors have been using combinations of options to achieve desired investment outcomes or specific payoff structures. With innovations in indexing, it is now possible to gain passive exposure to those predefined outcome goals. Before we begin to explore how those index strategies are constructed and how such access may be possible, it may be worthwhile to take a refresher on basic options.

The basic building blocks of option strategies are puts and calls. Since a call option gives an investor the right, but not the obligation, to buy an underlying security at a specified price (strike) within a specific time period, a call buyer may exercise the call and benefit when the underlying security goes above the option strike before the call expires. Conversely, a put option gives an investor the right, but not the obligation, to sell an underlying security at a specified price (strike) within a specific time period, therefore a buyer of a put may exercise the put and benefit when the underlying security goes below the option strike. In exchange of the potential benefit, an option buyer pays a premium upfront to the seller. On the other side of the trade, an option seller collects the premium as a compensation for potential loss by option expiration.

Exhibit 1 shows the payoff diagrams of the buyer and seller of an option contract.

Using the simple building blocks illustrated above, we will demonstrate how a hypothetical, complicated defined payoff may be achieved.

For example, a call spread can be constructed with a long call (at strike K1) that offers upside growth and a short call at a higher strike (K2). This structure is widely used in a range-bound or moderate bull market as a cost-efficient alternative to a long position in the underlying security. By the option expiration day, if the underlying security falls below K1, the call spread should have no loss other than the upfront net premium paid; if the underlying security rises above K1 and below K2, the call spread should offer 1:1 upside growth; when the underlying security rises above K2, the call spread return is capped. Exhibit 2 shows the payoff of a typical call spread with K1 = 100 and K2 = 120.

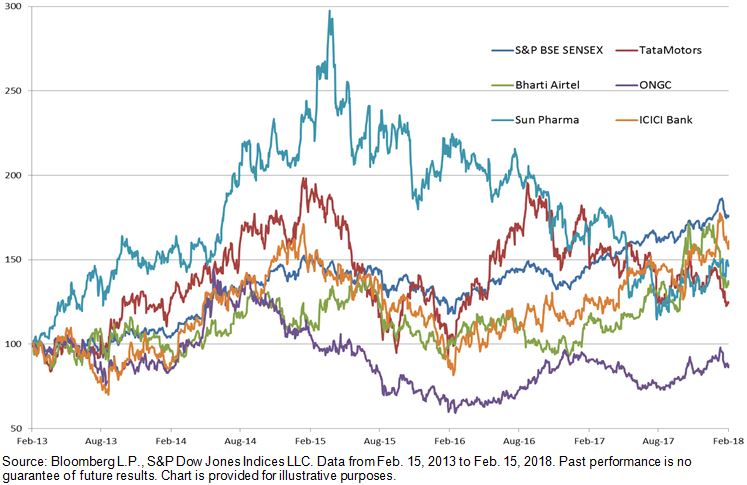

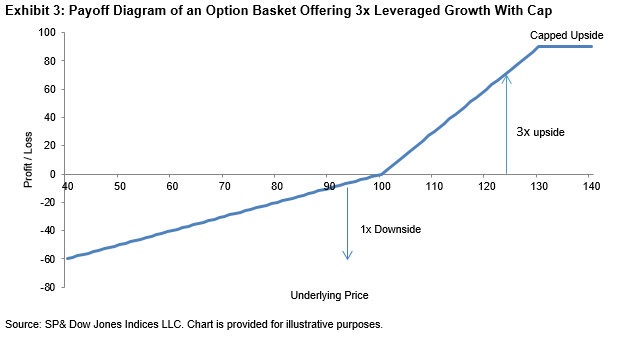

Using multiple option positions, we can further demonstrate a complex strategy to target specific outcomes, such as a strategy wishing to participate up to 3x of upside (with a cap) while limiting downside losses to only 1x (assuming the underlying security price is 100).

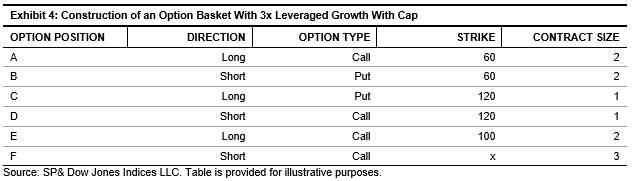

Now, the question is how does an investor achieve this payoff? A basket of options is used to construct this hypothetical portfolio.

Put-Call Parity theorizes that A and B are equivalent to a 2x leveraged, long-forward contract at strike 60 while C and D are equivalent to a short-forward contract at strike 120. The net effect of these four options is a net long-forward contract and a 1:1 exposure to the upside and downside. E offers another 2x exposure to the upside. Therefore, the basket offers 3x upside and 1x downside to the underlying security. The strategy also writes three call options F at a higher strike (x), which brings the cost of the option basket equal to a direct investment in the underlying security and the upside should be capped at x, consequently.

This example shows that using options to help achieve desired payoff can be a complicated tool. This is the main reason why these strategies have long been limited to OTC trading as bespoke solutions. Now, CBOE and S&P Dow Jones Indices have introduced a suite of benchmark indices that are designed to track the performance of some widely used target outcome strategies. One example is the CBOE S&P 500 3x Up, 1x Down Enhanced Growth Index Series, which seeks to offer the payoff as seen in Exhibit 3.

With these index-based defined outcome solutions, market participants can target precise payoff as they wish.