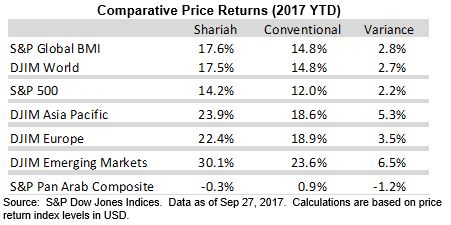

Most S&P and Dow Jones Shariah-compliant benchmarks outperformed their conventional counterparts year-to-date through September 27, 2017 as Information Technology and Health Care – which tend to be overweight in Islamic Indices – have been sector leaders, and Financials – which are underrepresented in Islamic indices – have experienced some weakness. One notable exception has been in the Middle-East where equity markets have very little exposure to Information Technology and Health Care, so Shariah-compliant indices have not benefited from the strength in these sectors.

Global Equities Power Higher in Q3 Led by Emerging Markets

Global equity markets powered higher in the third quarter adding to strong first half gains. As of September 27, 2017, the Dow Jones Islamic Market World and S&P Global BMI Shariah Indices each gained more than 17%, respectively, for the year, outperforming the conventional S&P Global BMI by nearly 300 basis points. Outside of the Middle-east, where the S&P Pan Arab Composite Shariah has underperformed the conventional S&P Pan Arab Composite, all other major regional Shariah-compliant indices remain well ahead of their conventional counterparts through late September.

The S&P 500 notched several new all-time highs in Q3. However, non-U.S. equity markets have posted the strongest year-to-date returns. Emerging markets sustained momentum in Q3 as improved economic sentiment and weakness in the dollar boosted interest in the asset class. The Dow Jones Islamic Market Emerging Markets Index has jumped over 30% for the year through September 27.

MENA Equity Markets Continue to Lag

Despite a rebound in oil prices during Q3, MENA equities continue to lag broader global equity markets as sustained geopolitical concerns have weighed on sentiment and the regional equity market has seen little benefit from the soft dollar and boom in technology stocks that has powered emerging markets more broadly. The S&P Pan Arab Composite Shariah declined 1.3% in the 3rd quarter through September 27, bringing the year-to-date return slightly into negative territory. The S&P Qatar BMI has experienced the steepest losses, falling 17.7% year-to-date, while Kuwait has been one of the few bright spots as the S&P Kuwait BMI has gained more than 20% on the year.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.