Active management is difficult; most of its practitioners underperform passive indices most of the time; and 2014 was a particularly tough year. Not surprisingly, active managers are not touting last year’s performance. Instead, the pitch for active management increasingly cites its putative social benefits — arguing, e.g. that “Markets are efficient only because active managers buy underpriced assets and sell overpriced ones.” Too much indexing, the argument goes, will produce inefficient capital markets and insufficient price discovery, as “not enough” investors trade in response to perceived misvaluation, and “too many” investors simply accept whatever price the market gives them.

At the limit, this is a logical argument; one academic observer compares misvaluation to street crime and active managers to police officers on the beat. More police, less crime; more active managers, less misvaluation. But:

- A completely passive investor buys the market portfolio and then, for all practical purposes, never trades again. In a world with some active investors and some completely passive investors, 100% of the trading is done by active investors motivated by perceived misvaluations. With lower trading volume, there may be wider fluctuations around fair value than there are now, but there’s no reason to suppose that fair value won’t continue to be the central tendency of prices.

- If the fluctuations away from fair value become “too wide,” the process is self-correcting. Wider departures from fair value mean bigger opportunities for the surviving active managers; bigger opportunities mean higher alpha for the successful; higher alpha means that assets flow back to active management. Just remember that, weighted by assets, no more than 50% of the active managers can be successful — otherwise said, that while bigger opportunities mean higher alpha for the winners, they also imply lower alpha for the losers.

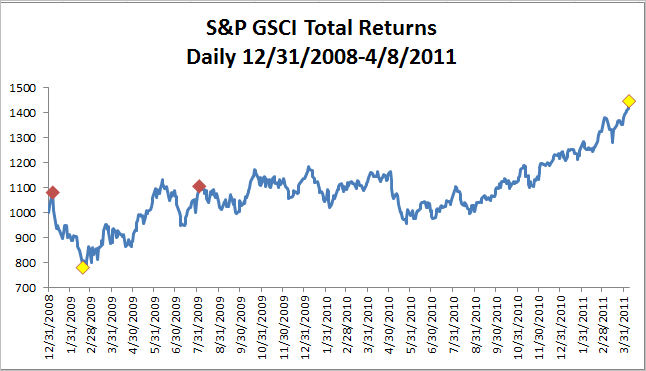

- Passive assets can rise dramatically without significantly diminishing the share of trading done by active investors.

The reason that passive assets can rise so dramatically is that active turnover is much higher than passive turnover. In the chart above, we assume that the average active fund turns over 100% annually versus only 10% for the average passive fund (a very generous estimate on the passive side). On those assumptions, if half of the market’s assets are indexed, active managers will still do 91% of the trading. Indeed, if 90% of the assets are indexed, active managers will do 53% of the trading.

It is trading, not asset ownership per se, that sets prices and putatively corrects misvaluations. If active trading makes for an efficient market, indexing has a long way to go before market efficiency is impaired.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.