In our last piece, we discussed the Bank of Japan’s (BoJ) monetary policy and how the yields of Japanese sovereign bonds have responded since 2016. The latest BoJ minutes released on June 26, 2017, reiterated that it “should continue with the current monetary policy,” while it also stated that it is “necessary to reduce the pace of purchases… in order to secure the stability and sustainability of JGB purchases.”[1]

Now that we understanding that the BoJ currently controls the yield curve by keeping the short-term policy rate at -0.1% and targets the long-term rate at around 0.0%, let’s take a closer look at how it has affected sovereign bonds and the yield curve.

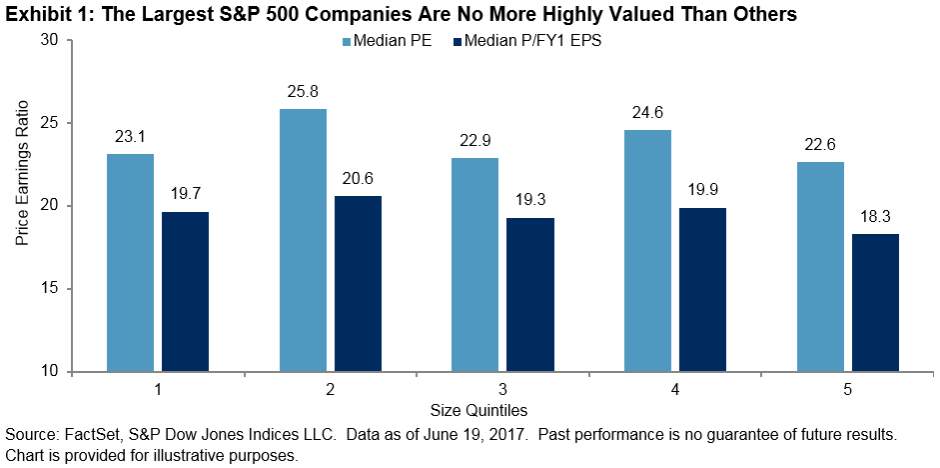

As of June 21, 2017, the S&P Japan Sovereign Bond Index tracks 302 bonds with a total market value of JPY 922 trillion, while the S&P Japan Government Bill Index measures the performance of 24 treasury bills with a market value of JPY 83 trillion. Among these bonds, JPY 607 trillion, or 60% of the overall exposure, have yield-to-maturity in the negative territory. These sovereign bills and bonds have maturities ranging from 2017 to 2025, with one-half maturing in the next three years (see Exhibit 1).

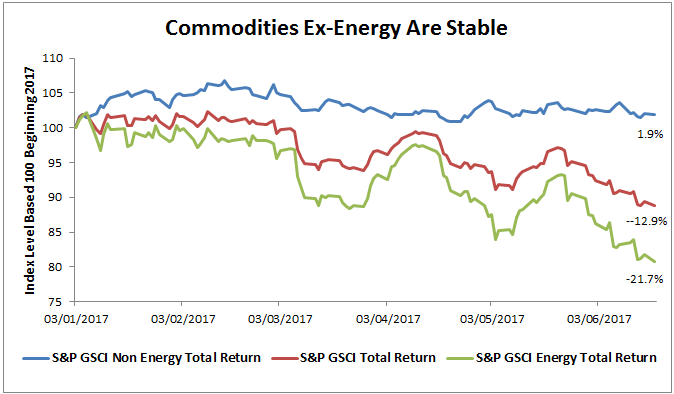

The yield curve is demonstrated in Exhibit 2. The 10-year period is the breakeven point where yield hovered around 0.06%, in-line with the BoJ’s target. The 15-year period had active issuances and the yield was about 0.28%, compared with the 20-year period at approximately 0.50%. The yield curve became flatter toward longer maturities, i.e. the 30- and 40-year period yields, which were around 0.80% and 1.0%, respectively.

Exhibit 1: Total Market Value in Negative Yields Versus Maturity Year

Exhibit 2: Yield-to-Maturity Versus Maturity

[1] Source: Bank of Japan. Data as of June 26, 2017. https://www.boj.or.jp/en/mopo/mpmsche_minu/minu_2016/index.htm/

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.