100 days…is it a milestone? Is it a key number? I’m not sure, but everybody looks like they love to write about it, so I will too. What I know is in Mexico we have a saying that goes, “If the U.S. sneezes, Mexico gets a cold.” Following Dennis Badlyans’s post “Does the Outperformance of UDIbonos to MBonos Have Legs?” from January, let’s see how Mexico’s fixed income indices have performed after 100 days with Donald Trump as President of the U.S., as well as how they had performed 100 days before the election when the polls were in the other direction. Furthermore, how had they performed in the days from the election until he began his presidency? Eight years ago we were living in different times but, how did the indices perform when Barack Obama began his administration?

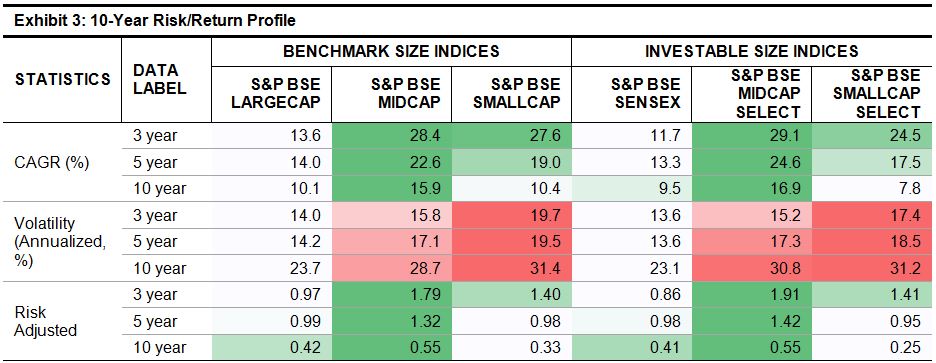

First, let’s start by taking a look at Exhibit 1, which shows the overnight reference rate, published by Mexico’s Central Bank (Banxico) and year-over-year inflation over the past 10 years.

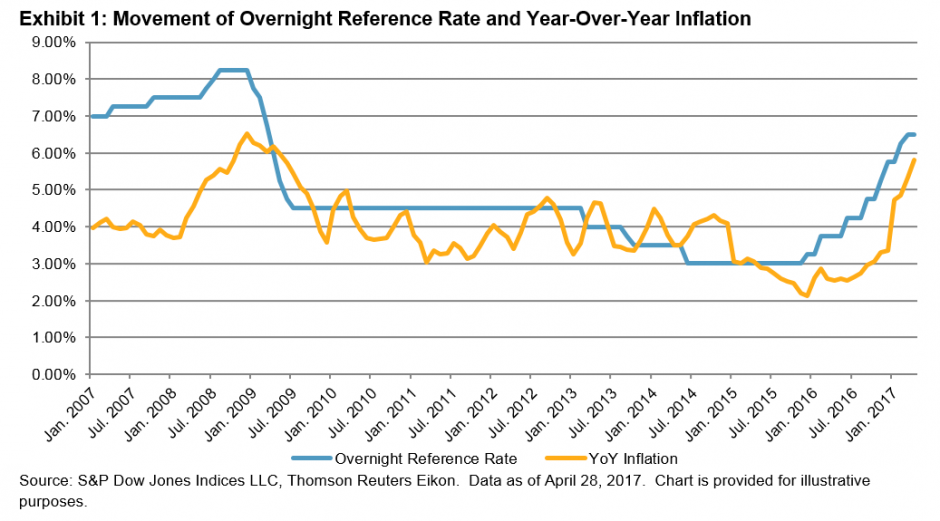

We can see for the overnight reference rate that recent rates are at the same levels as eight years ago, but the trend is the other way around from December 2015 until now, as interest rates have risen 350 bps, following or anticipating U.S. Fed movements. As for inflation, Mexico is hitting the same numbers as it was eight or nine years ago, after closing December 2015 with a historical minimum of 2.13% and closing April 2017 with 5.82%, far from Banxico’s objective of 3%. One key component to this movement has been the country’s currency—from December 2015 until now, the Mexican peso has depreciated more than 20% (see Exhibit 2).

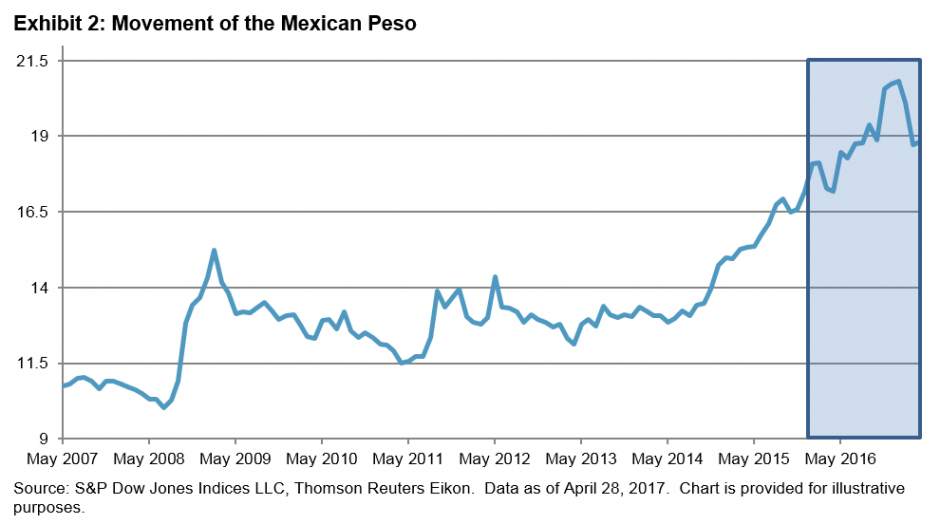

Exhibit 3 shows that 100 days before the election day in 2016, the Mexican peso gained 3% against the U.S. dollar, which could be attributed to the polls at the time. On the other hand, 100 days after Trump started his administration, the currency appreciated more than 14%. However, if we look at the period between Nov. 8, 2016 and Jan., 18, 2017, we can see a depreciation of 10.5%, with a historical EOD close for the Mexican peso on Jan. 10, 2017 of MXN 21.95 per dollar. For Obama’s administration, in the same three windows, we can see a depreciation of 24% 100 days prior election, almost 9% between election day and the start of his administration, and only a 2% appreciation in his first 100 days. The most relevant part of inflation for both is in the term of 100 days after, where during the Obama period, inflation came down 7.5% and during Trump’s period, it went up 73%.

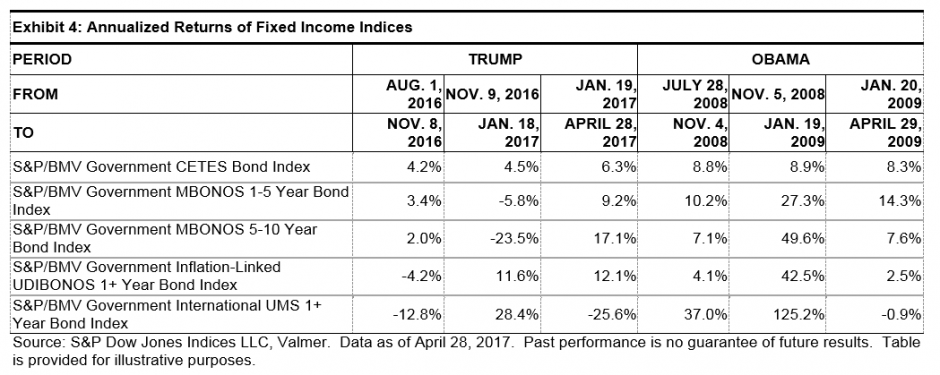

With all these movements, Exhibit 4 shows the annualized returns of five of Mexico’s fixed income indices.[1] It is interesting that for Obama almost every index, in every window, had positive returns except for the S&P/BMV Government International UMS 1+ Year Bond Index 100 days after, where it was down almost 1%, due to an appreciation of the currency. For Trump, most of the indices have been outperforming except for the 100 days after period, even with the hikes in the interest rates from Banxico. Exhibit 3 shows the yield for 5- and 10-year nominal bonds went down 30 bps and 54 bps, respectively, but we can see positive returns in the local indices. Also with Obama, due to the appreciation of the Mexican peso, the UMS index delivered negative returns.

See you at the next milestone.

[1] More information about these indices can be found here: S&P/BMV Government CETES Bond Index, S&P/BMV Government MBONOS 1-5 Year Bond Index, S&P/BMV Government MBONOS 5-10 Year Bond Index, S&P/BMV Government Inflation-Linked UDIBONOS 1+ Year Bond Index, S&P/BMV Government International UMS 1+ Year Bond Index.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.