A few weeks ago, Dennis Badlyans wrote about Mexico’s Fixed Income Markets and made a performance comparison of the different currencies of emerging markets, which illustrated how the Mexican peso has been the worst performer among its peers in 2016. The question is, what is driving the depreciation of the currency?

The answer in the short term, or on a daily basis, could vary from announcements of monetary policy in the U.S. and in Mexico, announcements of relevant economic data in the U.S., such as non-farm payroll, GDP estimates, or any emerging market news that could make the U.S. dollar stronger against other currencies.

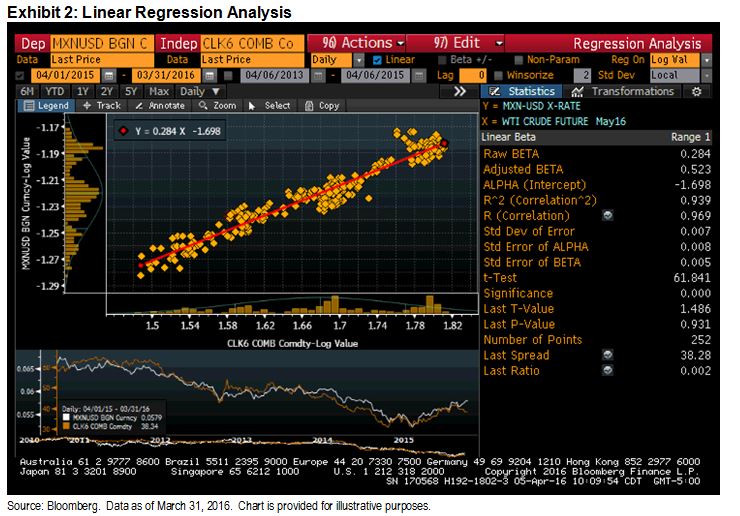

We could list a lot of examples trying to explain why the currency has fallen 14.1% over the past 12-month period ending March 31, 2016, or 32.1% in the previous two-year period, but Exhibit 1 shows how the price of oil has been one reason for this depreciation. The graph shows the price of the next oil future to mature, WTI May 2016, and on the left axis shows the inverse of the U.S. dollar to Mexican peso currency (pesos per dollar).

Doing a linear regression analysis of the log value using 252 of these two variables, where the variable “y” is the currency, we can see how dependent the currency is on movements in oil prices, with a correlation of 0.939 and an equation of y=0.284x – 1.698 (see Exhibit 2).

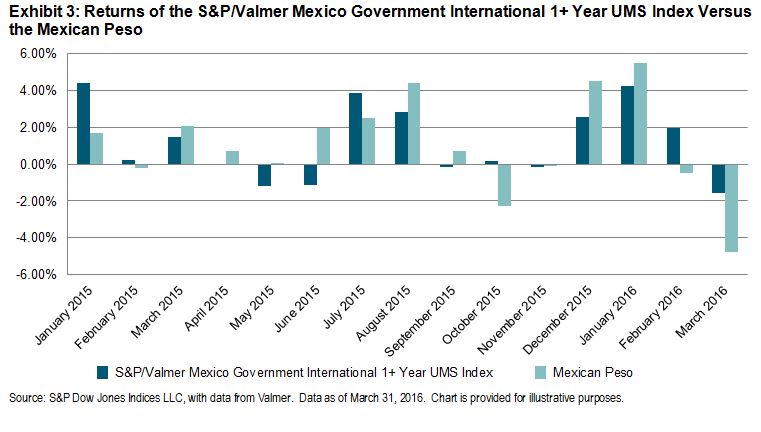

Given that the currency is a component of the performance of the S&P/Valmer Mexico Government International 1+ Year UMS index, Exhibit 3 shows the monthly returns of the index, with the performance of the Mexican peso making a considerable contribution to its performance.