If there were dreams to sell, a poet asked, what would you buy? Much more prosaically, if you could design your dream investment process, what would it look like?

A simple way to think about the question is to separate success into two dimensions: frequency and magnitude. Frequency means how often we “win” (i.e., how often our strategy outperforms its benchmark); magnitude measures the size of the winnings (i.e., the average value added when we win, and the average value lost when we lose). In the best of all possible worlds, we’d win most of the time, and the average outperformance in our winning months would be much higher than the average underperformance in our losing months.

Since we don’t live in the best of all possible worlds, compromise is necessary. Suppose we could only outperform half the time. Our investment process would still be a net winner if its wins were bigger than its losses — in other words, if its average outperformance (during winning months) were bigger than its average underperformance (during losing months).

Dispersion gives us a way to gauge the likely differences between the returns of a particular strategy and those of a market benchmark. This is true whether the strategy in question is active or is a factor or “smart beta” index. When dispersion is high, the strategy is likely to deviate from its benchmark by a relatively large amount; when dispersion is low, deviations are likely to be smaller. So: if our wins occur when dispersion is relatively high, and our losses when dispersion is relatively low — our investment process might still accumulate considerable value, even it wins only half the time.

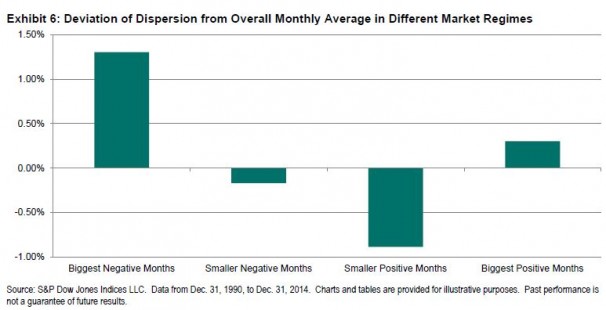

There’s a strong historical tendency for high dispersion and negative returns to go hand-in-hand, as shown here for the S&P 500:

When the S&P 500’s returns are at their most negative, dispersion tends to be well above average. When returns are positive, dispersion tends to be slightly below average. This means, other things equal, that a strategy that tends to win when the market is down and to lose when the market is up will have a natural performance advantage, since its hits will occur in times of high dispersion.

This is exactly the pattern of returns exhibited by low volatility indices, as well as by other defensive strategies such as the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats. We expect such strategies to do relatively well when the market declines. The remarkable thing about them is that they also tend to outperform over the long run, despite the market’s secular upward bias. Arguably, this is because they tend to win when dispersion is relatively high, and to lose when dispersion is relatively low. They are therefore more likely to outperform when the reward for outperformance is high.

Differential returns can often be a consequence of index dispersion. The distribution of dispersion favors strategies that outperform in down markets.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.