Diversification is undoubtedly a central tenet of investing. Many studies[1] [2] [3] have shown that over the long-term investment horizon, maintaining a diversified portfolio can potentially reduce overall risk without compromising expected returns. As such, most market participants strive to form diversified portfolios in order to achieve their desired investment outcomes.

There are many ways to achieve diversification within a goal-based portfolio. For example, in a multi-asset portfolio, allocating across various asset classes helps to ensure that returns are uncorrelated and risk is spread across the underlying asset classes. Within the same asset class, diversification can be achieved by investing in various investment styles, investing in international markets, or through cross-sector allocation.

Income-focused strategies can be diversified across multiple fronts—their sources of income (i.e., asset classes and sub-asset classes) as well as sectors from which underlying securities are drawn from. In this series of blogs, we focus on the latter and will demonstrate that incorporating sector diversification in an equity-only, dividend-focused portfolio can help improve the overall risk-adjusted returns of the portfolio.

Using the S&P 500® stocks as the underlying universe, we constructed three hypothetical yield-focused, large-cap strategies with quarterly rebalancing.

- Strategy 1 consisted of dividend-paying stocks;

- Strategy 2 consisted of stocks generating positive free cash flows[4]; and

- Strategy 3 consisted of stocks that exhibited both positive dividend yield and free cash flow yield characteristics.

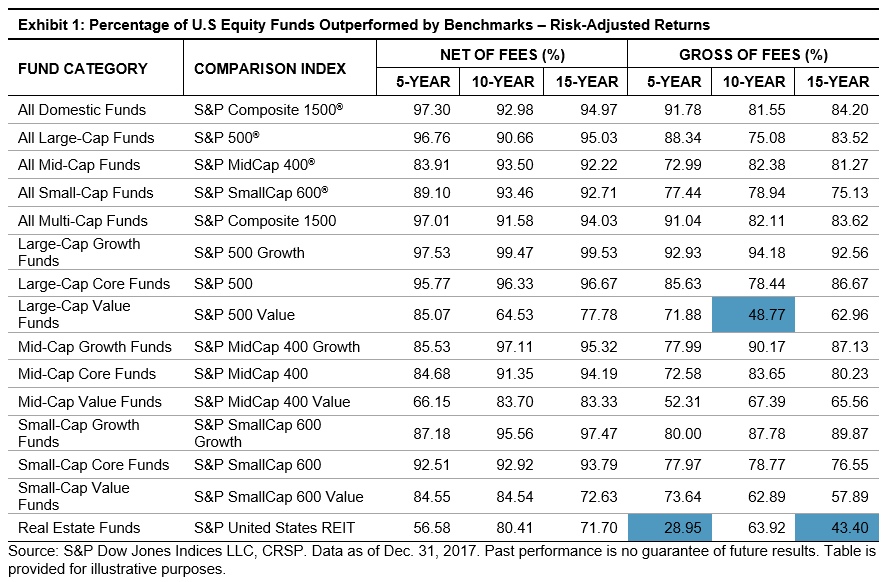

For each strategy, we ranked securities by their respective characteristics, with the higher values ranking better, and divided them further into five quintiled portfolios. Therefore, the top quintiles of Strategies 1, 2, and 3 were composed of stocks with the highest value of each category. As shown in Exhibit 1, for any given strategy, the top quintile had higher excess returns than the bottom quintile based on quarterly rebalanced data.

We see a clear linear relationship among all of the quintiles for the Free Cash Flow Yield and Dividend Yield + Free Cash Flow Yield strategies; that is, the first quintile portfolio (Q1) had higher excess returns than the second quintile (Q2), Q2 had better returns than the third quintile (Q3), and so on.

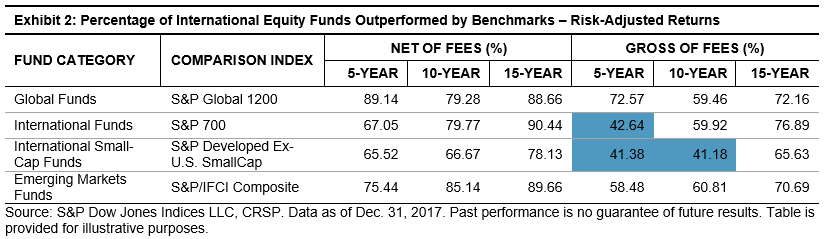

However, we did not observe the same pattern of returns for the Dividend Yield strategy. Here, the Q2 portfolio fared better than Q1. Suspecting that sector bias could be the driving factor, we compared the sector allocation of these two quintiles versus the underlying universe (see Exhibit 2).

Historically, companies in the utilities sector typically pay out high dividends. Therefore, it is not surprising to see that the Q1 Dividend Yield portfolio had a 25% average overweight in the utilities sector relative to the S&P 500. However, this overweight brought a negative effect to the portfolio. Similarly, its average underweight in information technology and financials also detracted from the performance. We observed the opposite for the Q2 portfolio, where those sectors contributed positively.

The attribution analysis shows that sector bias could negatively affect active and overall returns. In part 2 of this blog, we will discuss potential approaches to resolve the undesired sector concentration.

[1] A. Tabova, “Portfolio Diversification and the Cross-Sectional Distribution of Foreign Investment,” November 2013.

[2] K. Phylaktis and L. Xia, “The Changing Roles of Industry and Country Effects in the Global Equity Markets,” February 2007.

[3] S. Cavaglia, C. Brightman, and M. Aked, “On the Increasing Importance of Industry Factors: Implications for Global Portfolio Management,” March 2000.

[4] Free cash flow is the excess cash that a business has after paying all of the operations and capital expenditures.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.