Outstanding household debt reached a new high in the 2017 first quarter, surpassing the level set in the 2008 third quarter when Lehman Brothers failed and the financial crisis arose.

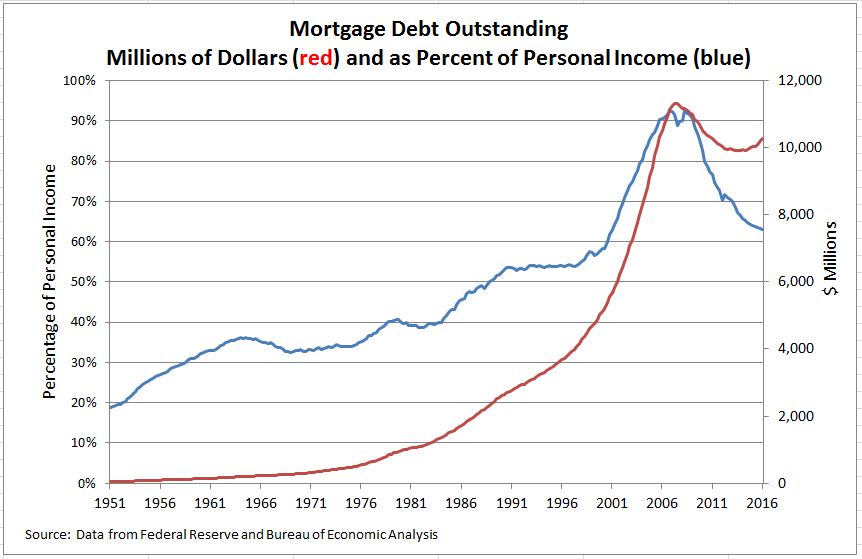

Despite worrisome comments in the press, there is no cause for concern. First, default rates on mortgages, auto loans and revolving credit are as low or lower than before the financial crisis. Second, the debt service ratio – the proportion of disposable income needed for the average household to service its debts — is 9.98%, close to its all-time low of 9.92%. Third, increases in consumer credit were responsible for setting a new high but mortgage debt is 10% below its 2008 peak. Add to this the growth in employment and there are no economic reasons for consumer spending to falter. The charts below provide further insight into household debt.

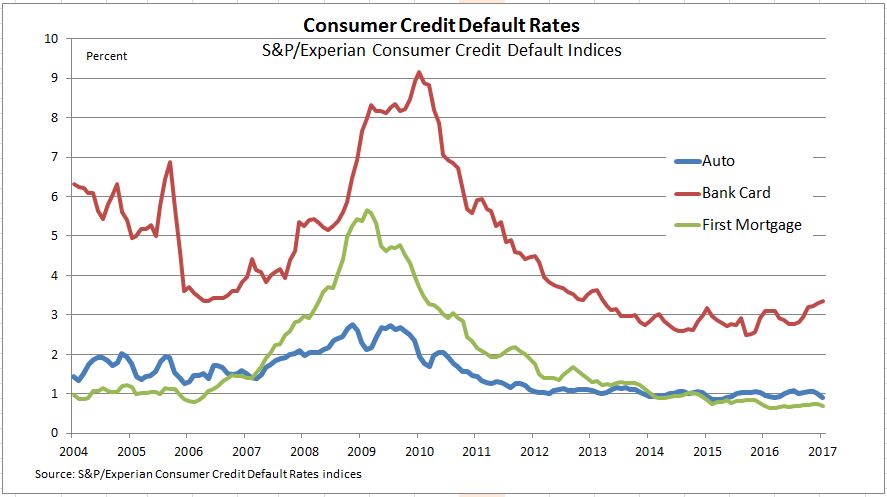

Default rates for mortgages and autos are both low and stable. “Bank cards” are credit cards like VISA, Mastercard or private label credit cards. These are revolving credit where an outstanding balance can be paid off at any time instead of a fixed payment schedule. The bank card default pattern is less stable and might be creeping up. The Federal Reserve’s recent survey of Senior Bank Lending Officers revealed that a small portion of banks were tightening credit standards for consumer borrowing.

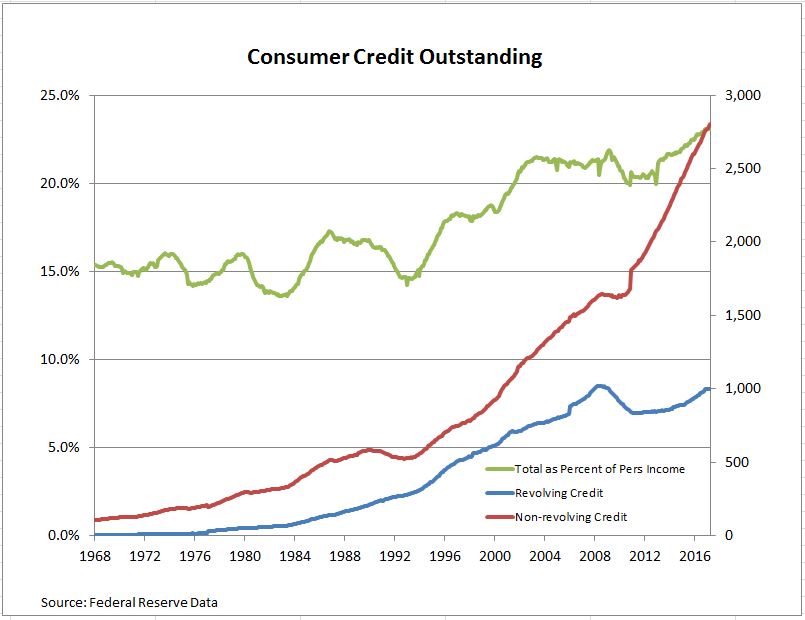

The second chart shows consumer credit outstanding for both revolving and non-revolving loans. Non-revolving loans include auto loans and are larger than revolving credit. They were less affected by the financial crisis. The green line is total consumer credit (revolving and non-revolving) as a percentage of personal income. This shows that the use of consumer credit expanded substantially after about 1996, leveled off between 2004 and 2008 and then recovered and continued to rise after the financial crisis. Whether attitudes about using credit shifted or wage gains had difficulty keeping up with spending isn’t clear from these data.

Student loan growth is significantly higher than other segments of consumer credit. In the last ten years, student loan debt grew at a 10% annual rate compared auto loan growth of 4.4% annually and little net gain in revolving credit.

Total mortgage debt for one to four-family homes is rising again and housing is recovering as shown by the red line. More interesting is the blue line which shows that household mortgage debt as a proportion of personal income peaked at over 90% then fell sharply as mortgages were paid off or written off as the economy expanded after the 2007-9 recession ended. Since mortgage debt was one of the problems leading the economy into the financial crisis, this suggests that there may be a cushion should another downturn loom up in the near future.

Debt tends to have a bad reputation in both history and literature. In economics it is worth noting that without debt and borrowing we wouldn’t have a capitalist economy or financial markets.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.