Over the years, we frequently hear from our SPIVA® and Persistence Scorecard readers that they have found their star manager or their own Warren Buffet—someone who can successfully beat the benchmark repeatedly. Based on our 15 years of publishing the SPIVA U.S. Scorecard, we know that, on average, around 20% to 30% of domestic equity managers successfully outperform the benchmark in any given year. We do not know, however, whether the same groups of managers outperform the benchmark over time. At the same time, the Persistence Scorecard informs us that the likelihood of a top-quartile manager maintaining the same success over three consecutive years is less than a random coin toss.

In order to identify the likely persistence of a manager’s ability to generate positive alpha (whether due to luck or skill), we studied whether a group of funds that outperformed their benchmarks in one period could persist in delivering alpha in consecutive periods. We measured this by tracking a group of funds that outperformed the benchmark on a rolling quarterly basis, based on three-year annualized returns. We then examined whether these outperforming funds (the “winners”) continued to outperform during each of the three subsequent one-year periods.

The University of Chicago’s Center for Research and Security Prices (CRSP) Survivorship-Bias-Free US Mutual Fund Database served as the underlying data source for our study. To avoid double counting multiple share classes, only the share class with the highest return in the previous period of each fund was used. At each measurement period, the universe, on average, consisted of over 2,300 active equity funds.

The study period was from March 31, 2000, through Sept. 30, 2016, based on the earliest availability of Lipper style classifications. On a quarterly basis, using three-year annualized returns for each of the funds in our universe as well as their corresponding benchmarks, we identified funds that beat their benchmarks. We then tracked their relative performance for each of the following three years.

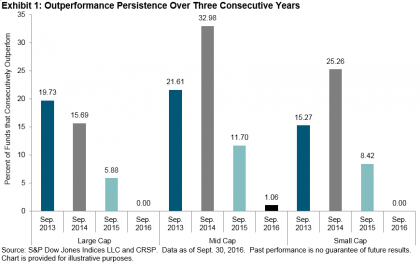

The results showed that, with the exception of large-cap value managers, there was negligible performance persistence across most domestic equity categories beyond a one-year horizon. For example, out of 1,034 large-cap funds that existed in the universe as of Sept. 30, 2013, only 19.73%, or 204 funds, outperformed the S&P 500®. In the following year, 15.69% of those 204 funds outperformed the benchmark. By the end of the third year, none of those original 204 funds were able to outperform the S&P 500 on a consecutive basis (see Exhibit 1).

A point-in-time snapshot of the performance persistence figure can be unduly influenced by cyclical market conditions. Therefore, we also computed the rolling quarterly average performance persistence figures from March 31, 2003, through Sept. 30, 2016. For more detailed results, please see the research paper, Fleeting Alpha: Evidence From the SPIVA and Persistence Scorecard.

Taken together, the data indicate the difficulty that market participants face in finding a skillful manager that can offer consistent alpha on a near- to medium-term basis. Therefore, market participants may not be best served by chasing hot hands or picking managers based solely on past performance.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.