After China reported year-over-year first-quarter growth that showed signs of improvement, it overpowered negative news of the Doha oil production meeting failure and sent commodities rallying. Investors’ attention quickly shifted from oil to the other economically sensitive sector, industrial metals.

Many believe the uses for metals in construction and automobile manufacturing are the driving force behind the sector. Copper even earned its nickname “Dr. Copper” for its supposed ability to indicate the economic health of China. However, data shows Dr. Copper is not so smart and that this rally is from the weak dollar and supply shocks rather than Chinese GDP (gross domestic product) growth.

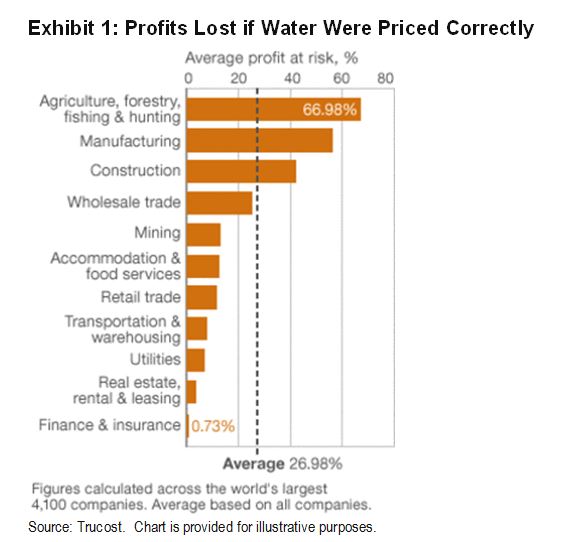

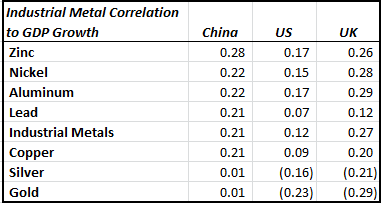

The first myth is that copper and industrial metals are correlated to economic growth, especially China’s. Using year-over-year data since 1978, the correlation of copper to Chinese GDP growth is only 0.21, and is actually the lowest of all the industrial metals. The most correlated metal is zinc but the relationship is still weak at only 0.28.

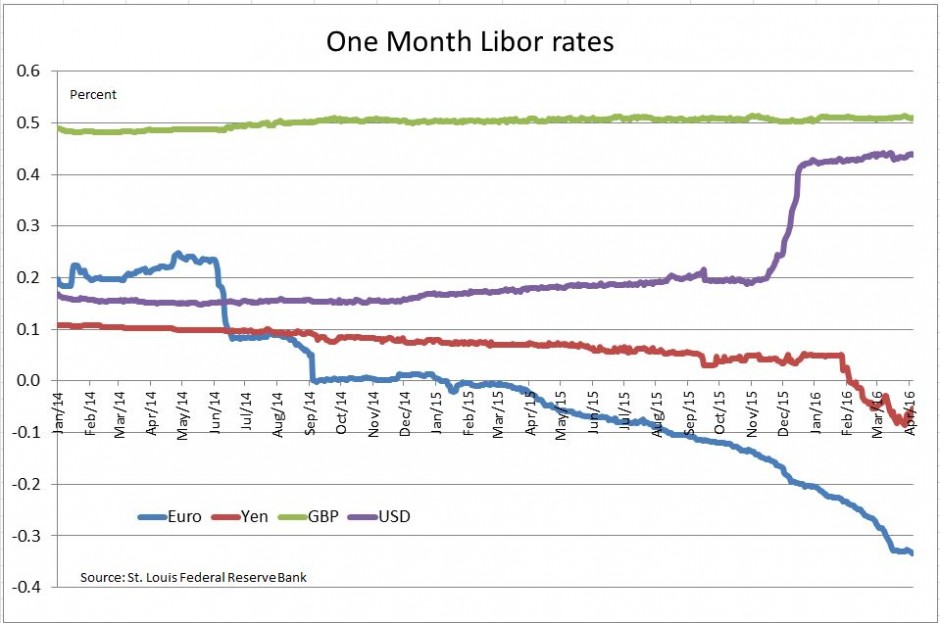

Even if Chinese demand might not be enough to boost the metals, there is still hope for the sector. The correlation of metals to the US dollar has a higher (and inverse) relationship than to GDP growth, but the correlation is still only moderate.

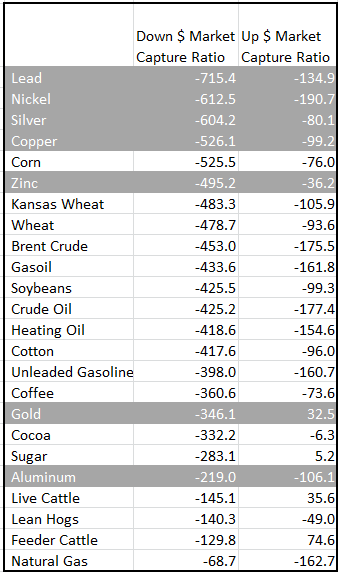

However, the weakening dollar helps metals more than any other commodity sector. In the past 10 years, for every 1% move down in the US dollar, gains in lead, nickel, copper, zinc and aluminum have been 7.2%, 6.1%, 5.3%, 4.6% and 2.2%, respectively. Also, silver has gained 6.0% and gold has gained 3.5% for every 1% slip in the dollar. The weak dollar helps far more than a strong one hurts.

Besides the tailwind of a weakening dollar, there are noticeable shortages that have appeared. March was the first month the industrial metals sector was in backwardation since September 2015 and marked the third time in 18 months – that hasn’t happened since 2007, before the financial crisis.

Within the sector, there have been recent shortages in industrial metals from lead, copper and aluminum. While copper has more shortages than excess inventories throughout history, its roll yield has grown (measuring a shortage) 60% in the first quarter. Also, lead showed a shortage in Feb for the first time since Nov. 2012, but now is a seasonally weak time for lead as the winter demand for replacement automobile batteries slows. However, the support for aluminum could be more persistent from stockpiling and tax policies. It is very rare to see shortages in aluminum. There have only been 10 months in 10 years with a positive roll and it seems to be driving the whole sector.

Notice the dramatic decline over the year in warehouse stock levels too.

Zinc has gained more than gold this year and is the best performer in the sector, up 20.5% in 2016. Its excess is half of what it was in October. Supply cuts and mine closures have boosted returns. “Zinc inventories dropped for a 28th straight session to 413,250 metric tons, the lowest since August 2009, as supply cuts and the closing last year of China’s MMG Ltd. Century mine and Vedanta Resources Plc’s Lisheen mine boosted the need for supplies on exchanges. Chinese new-home prices rose last month in 62 of 70 cities tracked, compared with 47 cities in February, helping boost the demand outlook for the metal.” – According to Bloomberg, stockpiles are the lowest in more than six years.

Nickel hasn’t seen a shortage since 2011, despite its huge price spike in 2014 of more than 50%. The suppliers are producing relentlessly to try to squeeze out marginal producers for market share – much like what is happening in the oil market. Except the role of China is flipped. Nickel producers want to squeeze China out, yet China is the oil customer everyone wants.

So, the story isn’t as simple as “Chinese demand growth boosts copper (or industrial metals).” While the demand growth may help, the dollar and supply side are the more important factors for the sector. If the demand grows at the same time the supply is disrupted and the dollar is weak, it may be a best case scenario for the industrial metals.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.