Despite the fact that many single-factor strategies have empirically delivered positive excess returns in the long run, they have suffered periods of substantial underperformance under certain market conditions due to their cyclicality. Blending a number of desired factors with low correlations is a potential way to attain more balanced and diversified portfolios. The obvious questions that arise are: Are they likely to achieve better performance? How do they behave in different financial environments?

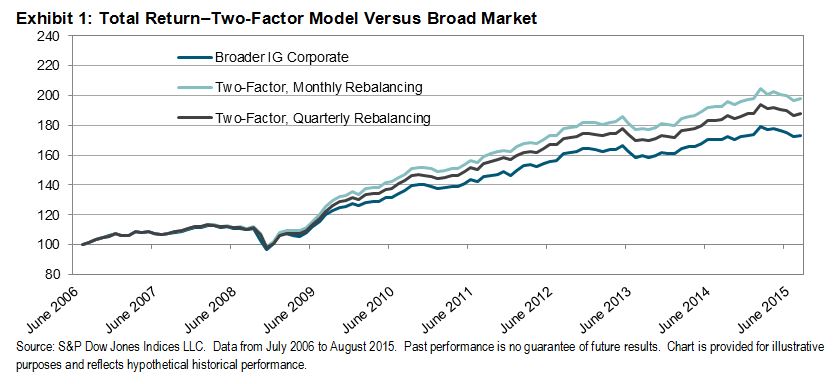

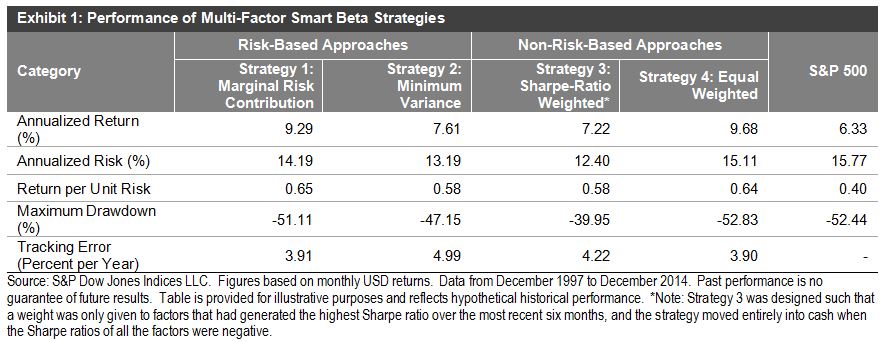

Our stylized portfolios that blend six factors (volatility, value, quality, size, momentum, and dividend yield) with four different strategies (marginal risk contribution, minimum variance, Sharpe-ratio weighted, and equity weighted) demonstrated higher risk-adjusted returns than the S&P 500®, with a lower tracking error than most single-factor strategies (see Exhibit 1).

Over the entire period, marginal risk contribution and equal-weighted strategies exhibited less cyclicality than other multi-factor and most single-factor strategies. They achieved more consistent and higher excess return than other strategies across various market cycle phases. On average, they produced higher information ratios and a higher incidence of outperformance during recovery and bearish periods.

The minimum-variance strategy had a significantly lower information ratio and a lower incidence of outperformance in bullish and recovery markets, similar to, but less defensive than, the single low-volatility strategy. The Sharpe-ratio-weighted strategy performed well in bear markets, but it significantly lagged the S&P 500 in recovery periods. This suggests that using recent momentum to tilt factor exposures did not improve the risk-adjusted return of the multi-factor portfolio, even though it had a lower drawdown as a result of the strategy moving into cash during the global financial crisis.

For more information on our research on multi-factor smart beta strategies, please click here, where you will also find details about:

- What is driving risk/return of various smart beta strategies, and

- How each of the smart beta strategies have performed in different macroeconomic and market environments.