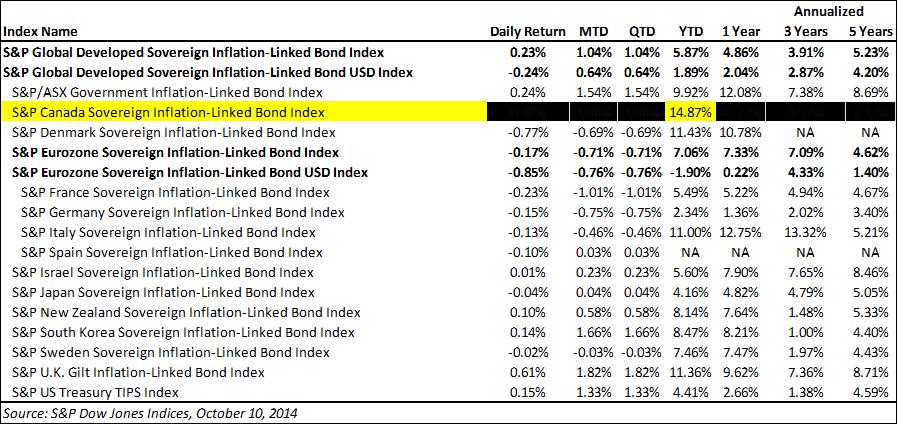

The S&P Canada Sovereign Inflation-Linked Bond Index has returned 1.8% month-to-date and an outstanding 14.87% year-to-date. Investors of inflation-linked bonds are interested in the real yield which measures a bond’s yield adjusted for inflation. Canadian inflation (2.1%) has recovered in recent months from the low end of the Bank of Canada’s 1% to 3% target range.

Inflation-linked bonds are not just a hold-to-maturity strategy. Inflation expectations vary with economic conditions and so by varying the weightings of nominal and inflation-linked bonds in a portfolio, investors can take views on movements in those expectations.

Currently in Europe, the ECB has been fighting deflationary pressure and looking to revive growth. U.S. style asset purchases supported by ECB President Mario Draghi are the latest action to stimulating the feeble economy. Though, strong demand for a new Spanish inflation-linked bond to settle Oct. 14th suggests the belief that the ECB policies will stave off deflation and increase consumer prices. A modest recovery in inflation might be expected by some as the weak euro versus the dollar could lead to increased price pressures. Year-to-date the S&P Eurozone Sovereign Inflation-Linked Bond Index has returned 7.06%.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.