One of the common misconceptions in finance is that companies from the Information Technology (Tech) sector do not pay dividends. While this may have been the trend a long time ago, this has certainly not been the trend over the past 10 years. Over the past 10 years, within the Tech sector of the S&P 500®, 26 companies initiated dividend payments and 59 companies increased their dividends at various points throughout those years, for a total of 376 dividend increases in the sector.

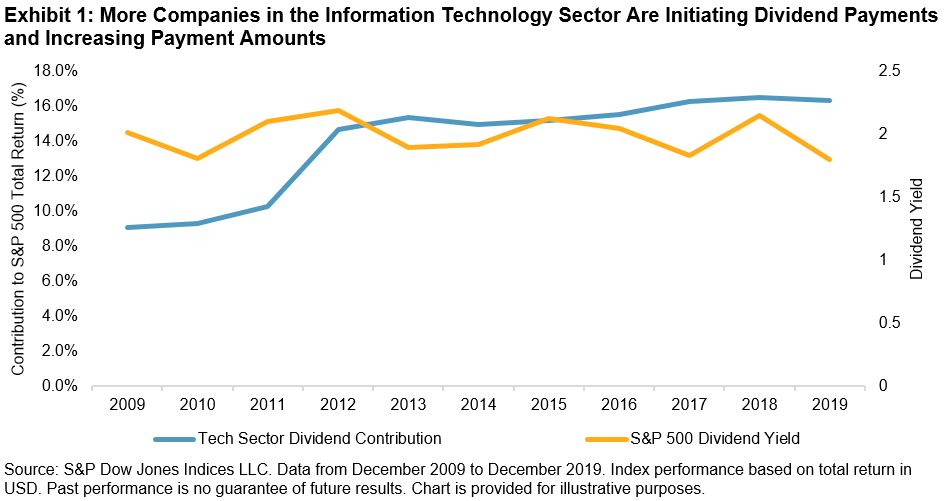

During the same period, with an increasing number of Tech companies paying dividends, the contribution to S&P 500 total return by these companies rose from 9.07% in 2009 to 16.33% in 2019 (see Exhibit 1).

With the changing characteristics of the Tech sector, there is a need to measure the performance of dividend growers in this sector. Responding to market needs, S&P Dow Jones Indices recently launched the S&P Technology Dividend Aristocrats® Index, which seeks to track the performance of Tech companies that have a history of consistently increasing dividends.

Exhibit 2 shows the potential benefit of focusing on these companies: the S&P Technology Dividend Aristocrats Index provided similar risk-adjusted returns to the companies from the S&P TMI that are classified in the Tech sector over three- and five-year horizons, with lower volatility and higher dividend yield. The risk/return profile also compared favorably to the widely followed S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats Index.

Given the results in Exhibit 2, it is perhaps unsurprising that the S&P Technology Dividend Aristocrats Index experienced lower volatility and lower drawdowns during a recent period of market turbulence. For example, the maximum drawdown for the S&P Technology Dividend Aristocrats Index (-19.5%) during Q4 2018 was less than that for the S&P TMI Information Technology (-23.6%). Exhibit 3 provides us with a more detailed view of the daily drawdown for this period.

The S&P Technology Dividend Aristocrats Index can be complementary to the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats, as the latter tends to be underweight in the Tech sector relative to the S&P 500—as of Dec. 31, 2019, the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats was 20% underweight in Tech. Given the growing importance of Tech companies in driving S&P 500 returns, the S&P Technology Dividend Aristocrats Index ensures relevant allocation to the sector.

Incorporating the S&P Technology Dividend Aristocrats Index in a portfolio with an existing allocation to the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats could provide greater diversification benefits. Exhibit 3 shows the back-tested returns of a hypothetical portfolio that allocates 80% to the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats and 20% to the S&P Technology Dividend Aristocrats Index. These weights were chosen to ensure a 20% weight in the Tech sector for the portfolio. We can see that combining the two Dividend Aristocrats indices in a single index resulted in a better risk/return profile than either individual index in the long-term.

The S&P Technology Dividend Aristocrats Index is designed to measure the performance of Tech companies with a history of raising dividends. The performance of the index has shown that it has a similar risk/return profile to the broader sector, with lower volatility and higher dividend yield. Ultimately, the index enables dividend-focused market participants to gain exposure to the Tech sector while maintaining growth and value characteristics.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.