Uncertainty has been a common theme throughout 2019, and the third quarter proved no different. The quarter was dominated by uncertainties surrounding the U.S.-China trade talks as well as falling global growth forecasts. Demand for high-quality fixed income assets increased, pushing the yield on the 10-Year U.S. Treasury Bond down 34 bps. In spite of the mixed economic data and trade tensions, equities finished the quarter in positive territory, with the S&P 500® returning 1.7%.

As Exhibit 1 shows, the S&P Risk Parity Indices built upon the new highs set in Q2 2019 to post modest gains in Q3 2019.

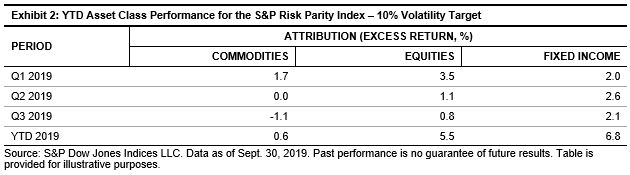

Exhibit 2 shows the performance attribution for the S&P Risk Parity Index – 10% Volatility Target, where we can observe that the majority of the YTD performance came from equities and fixed income in the midst of contrasting sentiments across these two core asset classes.

Looking to the future, with many unpredictable variables at play—such as interest rates, bond yields, equity volatility, inflation, and more—what does the S&P Risk Parity Index Series have to offer?

The short answer is: a lot. These indices aim to generate stable returns across a range of economic environments, specifically growth and inflation. By allocating across three core asset classes—equities, fixed income (nominal bonds), and commodities—the indices strive to perform well or outperform traditional investments across rising and falling growth and inflation.

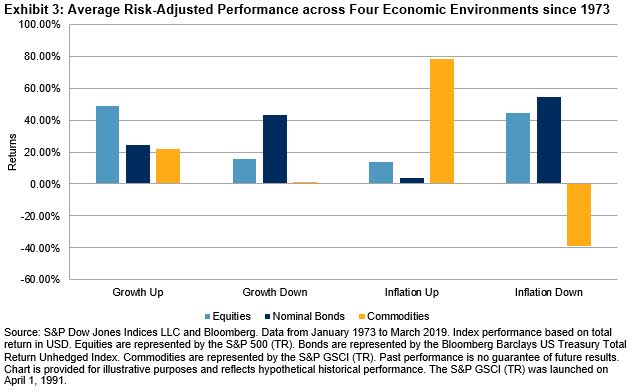

Across the growth dimension, equities and bonds are complementary. As growth rises or is better than expected, stocks tend to rise due to better earnings, whereas nominal bonds tend to perform less well. The opposite is true when growth falls or is weaker than expected.

Across the inflation dimension, equities and bonds are less complementary, as both are expected to perform well during periods of low or falling inflation, and less well during periods of rising inflation. Hence, commodities play an important role by offering inflation protection.

Exhibit 3 shows the average monthly risk-adjusted returns across asset classes during the four economic environments since 1973. The growth indicator uses the Chicago Fed National Activity Index (CFNAI), a monthly index designed to gauge overall economic activity (growth up if greater than 0; growth down if less than 0). The inflation indicator uses the US CPI Urban Consumers YoY NSA series (inflation up if higher than prior month; inflation down if lower than prior month).

Unsurprisingly, equities performed strongly during a growth up environment, and nominal bonds performed well during a growth down environment. With respect to inflation, commodities provided a natural hedge to equities and nominal bonds during rising inflation and vice versa. Thus, within each environment, one or more asset class historically served to offset any underperformance.

The foregoing begs the question: are the S&P Risk Parity Indices expected to outperform in every environment? The answer is no. The S&P Risk Parity Indices tend to underperform during strong bull markets. This could be expected given the higher equity allocation that traditional portfolios often have. Additionally, the indices tend to underperform during a rapidly rising rate environment. However, it is important to note that when rates rose gradually over time, risk parity historically performed fairly well.

It is hard to predict what the future has in store, but the S&P Risk Parity Indices appear to be well-positioned for whatever lies ahead in this uncertain landscape.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.