Socially responsible investing (SRI) has deep roots in the South African market. Indeed, some of the earliest records of this type of investing date back to the boycotts against South African companies during the era of Apartheid. The movement paved the way for a generation of socially conscious investors seeking to affect social change, giving renewed meaning to the adage of “putting one’s money where one’s mouth is.”

As an investment strategy, SRI removes “sin” stocks such as tobacco, alcohol, and weapons from portfolios with negative screens. Values aside, this is potentially risky due to a lack of portfolio diversification. SRI therefore got somewhat of a bad rep for being “values-based investing” in mainstream finance circles. But contrary to what mainstream investors might think, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing, on the other hand, is not some virtuous strategy relegated to those investors who are willing to put their beliefs before their returns. ESG can simply be a prudent approach to encompassing a broader information set that focuses on material issues with the potential to affect the long-term viability of company business models.

For example, the value of a company like Aspen Pharmacare is not only driven by its physical assets, but also by its innovation and access to patients. With rising healthcare costs and diminishing patient trust in providers, a holistic valuation might also consider its intangible assets like innovation management and business ethics. These are, to a large extent, informed by metrics such as R&D productivity, product recalls, and customer satisfaction—precisely the types of issues that would get captured by a diligent ESG research process. Though there are many sustainability topics to consider, they are not all relevant. ESG can, and often does, simply focus on the most financially material factors for a given industry.

The Myth of an ESG versus Performance Tradeoff

Since the early days of SRI, sustainability data has greatly improved. Companies increasingly disclose to qualify for exchanges like the JSE SRI Index that was launched in 2004. While initiatives such as the King Code on Corporate Governance (with various iterations from 1994-2017) have played a role. Investor demand for greater transparency has also risen with growing awareness of the materiality of ESG issues.[1] Revised Regulation 28 of the Pension Funds Act in 2011 calls for trustees to assess the materiality of ESG factors in their investments, on which FSCA released additional guidance in June 2019. Furthermore, the 2011 Code for Responsible Investing in South Africa encourages institutional investors to integrate ESG into their investment process as well. Investors are thus pushing for more information on the sustainability performance of the companies they own.

The data that has emerged offers the possibility of nuanced approaches to responsible investing—amplified by the launch of S&P DJI ESG Scores.[2] The scores unleash decades of sustainable investing insights and variation in sustainability characteristics among companies within even the same sector. With such datasets, inclusive approaches to tilt, reweight, or optimize a strategy rather than simply exclude sectors are now possible. Thus, with industry-neutral approaches, ESG investing need not imply a tradeoff with returns. For example, the S&P South Africa Domestic Shareholder Weighted (DSW) Capped ESG Index outperformed the benchmark over the past three-year period (see Exhibit 2). By targeting 75% of market cap by ESG rankings within industry groups, whose weights remain unchanged, the index offers a compelling rebuttal to the myth of an ESG versus performance tradeoff.

A Real (Economy) Problem

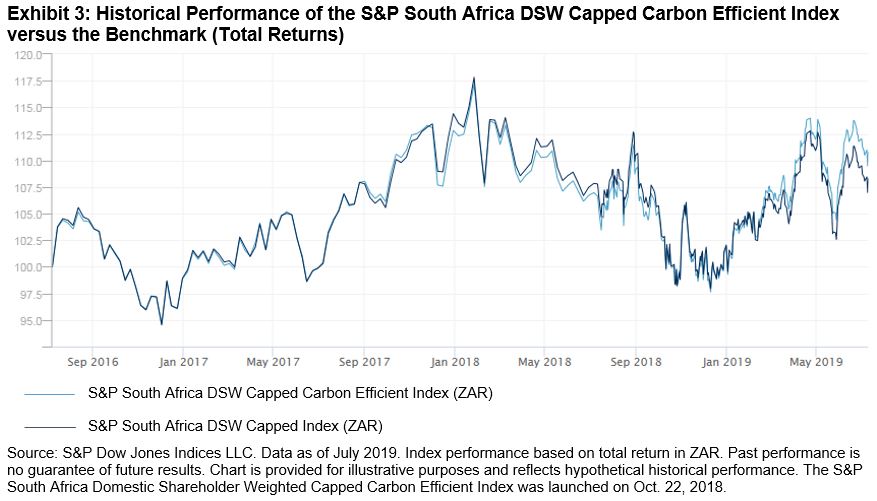

ESG can also help to address unprecedented trends unfolding in the global economy. Some of which, like global warming, invite policy responses that translate these real economy impacts into material concerns for investors. For instance, measures like the South African Carbon Tax Act No. 15 are, by design, transforming the underlying economics to favor carbon-efficient technologies across all industries. Investors looking to safeguard against the rising costs of a carbon-intensive portfolio might thus opt for low-carbon solutions, like the S&P South Africa DSW Capped Carbon Efficient Index (see Exhibit 3). The index closely tracked the benchmark over the past three years and achieved a 58% carbon reduction as of July 2019,[3] demonstrating that investors can make good on their values without compromising their returns.

A Primarily Pragmatic Approach

Not to be confused with SRI, which is deliberately principled, ESG offers a pragmatic approach to addressing financially material issues through a broader information set. ESG index solutions can facilitate similar—if not better—risk/return profiles to broad market benchmarks, upending the view that this type of investing necessarily implies a trade-off with returns. The added possibility of achieving some positive social impact might just be a bonus.

[1] A 2007 report led by UNEPFI found that 70% of South African investment professionals surveyed claimed that most ESG issues were at least somewhat material in “evaluating the likely performance of investments.”

[2] For more information about S&P DJI ESG Scores see here: https://spdji.com/documents/education/education-discover-material-insights-with-sp-dji-esg-data

[3] Calculated using Trucost carbon emissions data based on the aggregation of operational and first-tier supply chain carbon of index constituents per USD 1 million in revenue (tCO2e / USD million). For more information, visit www.spdji.com/esg-metrics.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.