In a previous blog,[1] we explored historical dividend payers in the Colombian equity market, focusing on the S&P Colombia BMI as the underlying universe, highlighting the number of dividend payers, market capitalization, and GICS® sector distribution. Building on that, we now examine if the Colombian market has rewarded dividend payers over non-payers.

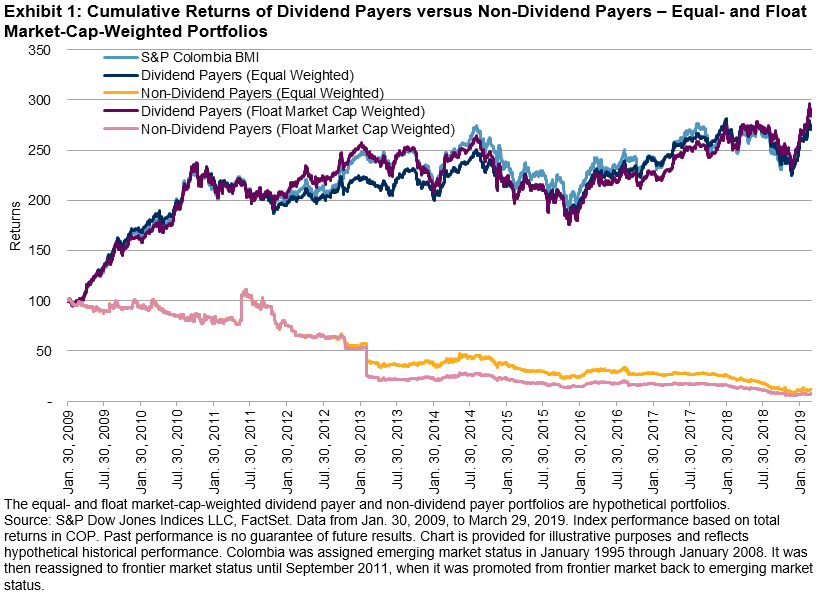

As a starting point, we formed hypothetical portfolios by grouping the underlying universe into dividend payers and non-dividend payers. Portfolios are float market cap weighted as well as equal weighted to remove any size bias. Each portfolio rebalances semiannually in March and September. The 10-year back-tested performance shows that both equal-weighted and float market-cap-weighted dividend payer portfolios outperformed non-dividend payers on a cumulative basis (see Exhibit 1).

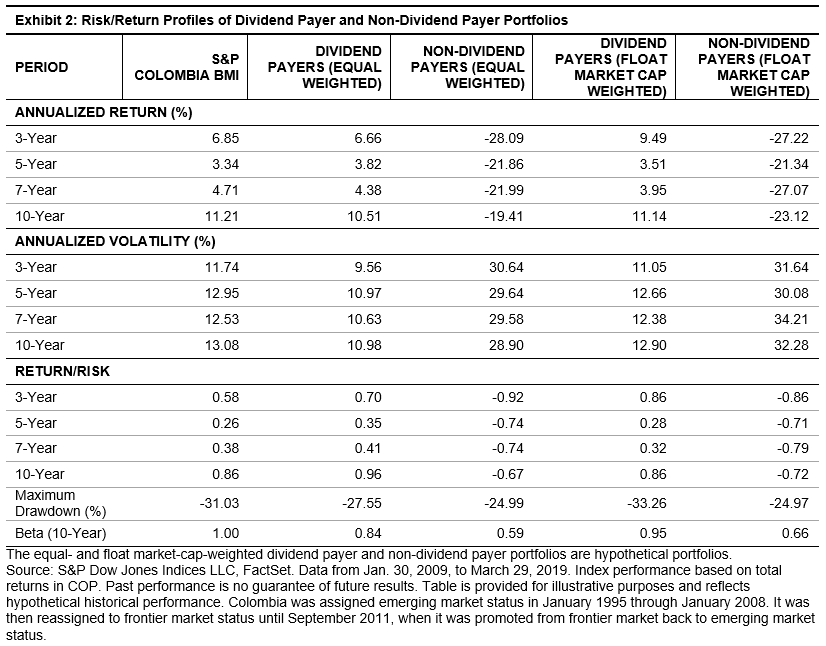

The risk/return profiles of the hypothetical portfolios (see Exhibit 2) reveal that the dividend payer portfolios outperformed the non-dividend payer portfolios on a risk-adjusted basis. It is worth noting that the realized volatilities of the dividend payer portfolios were lower than the broad market as well as the non-dividend payer portfolios, for equal-weighted and float market-cap-weighted versions. The betas of the dividend payer portfolios were higher than those of non-dividend payers, coming in close to one. Therefore, the dividend payer portfolios were more sensitive to the market.

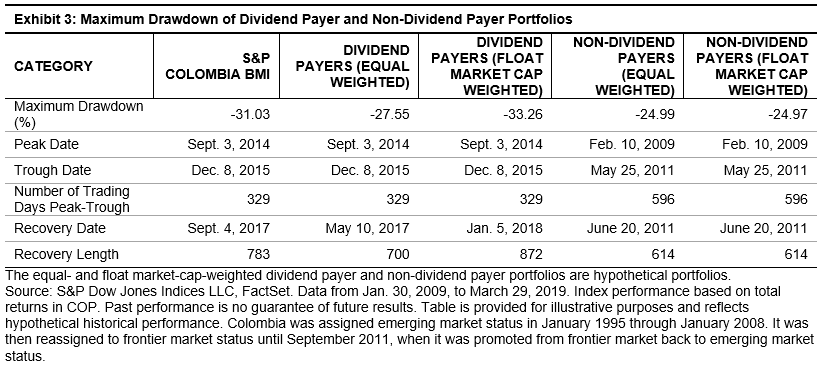

Similarly, dividend payer portfolios had higher maximum drawdowns than non-dividend payer portfolios. Exhibit 3 shows that the largest drawdowns for non-dividend payer portfolios were similar for both weighting methods. Although the dividend payer portfolios’ peak and trough dates were in line with the market, maximum drawdowns and recovery lengths were larger for capitalization-weighted portfolios.

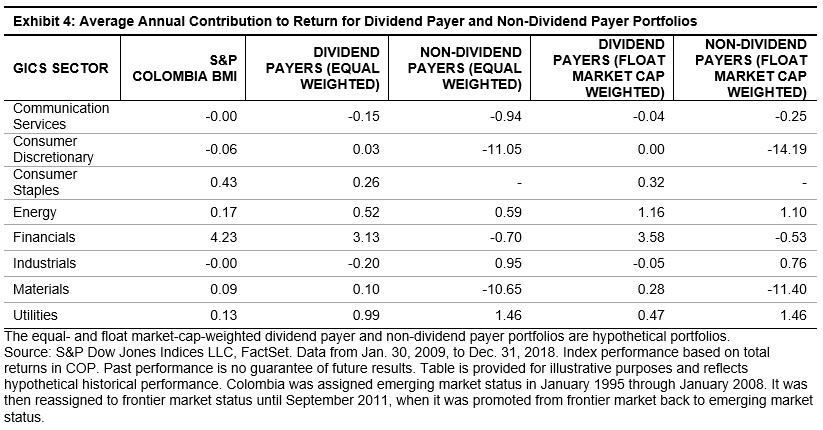

Next, we looked at the average annual contribution to return over the 10-year period, broken down by sectors (see Exhibit 4). We can see that dividend payer portfolios followed a similar distribution to that of the underlying universe, with Financials being the largest contributor, followed by Utilities and Energy. This result is consistent with our previous blog, where we highlighted that these sectors were the largest contributors to dividend yield. For the Energy sector, which contains only one security, the free-float portfolio contribution was larger than the equal-weighted version.

For the non-dividend payer portfolios, Consumer Discretionary and Materials were the biggest detractors. Financials slightly underperformed and Industrials issues outperformed their dividend payer counterparts, while Consumer Staples had zero contribution, as all the Consumer Staples securities pay dividends. The Utilities and Energy sectors also added positively for all the portfolios, while Communication Services contributed negatively to all portfolios.

Overall, the Colombian equity market has seemed to prefer dividend payers to non-dividend payers. This finding implies that dividend-based strategies are feasible, but market participants may want to address potential sector concentration issues.

[1] https://www.indexologyblog.com/2019/05/22/examining-dividend-payers-in-colombia/

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.