Not all indices are created equally, especially those representing US small-cap equities. Many investors are surprised to learn that the S&P SmallCap 600 has outperformed the Russell 2000 by 2% annualized since inception (Dec. 31, 1994.) This outperformance is persistent through different time periods, bull and bear market cycles, and with less risk. The performance results of the S&P SmallCap 600 should redefine and raise the bar for passive small-cap beta.

This is the 2nd part of our blog series containing excerpts from our new paper where we discuss the outperformance of the S&P SmallCap 600 versus the Russell 2000, the performance of the indices compared with active managers, and the case supporting the performance.

THE S&P SMALLCAP 600 OUTPERFORMS THE RUSSELL 2000

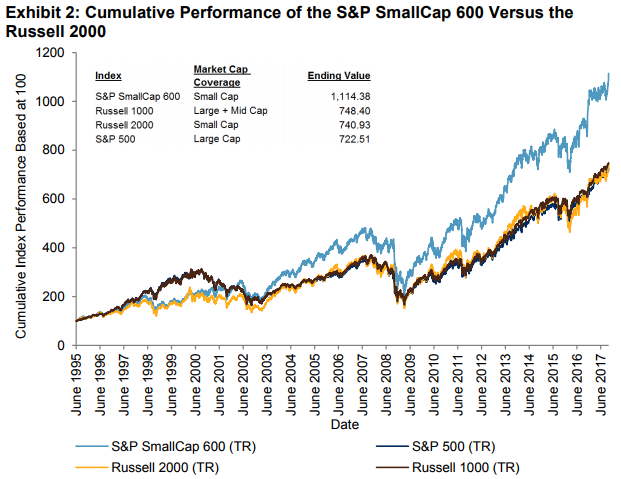

Let’s begin with a simple example to demonstrate the long-term outperformance of the S&P SmallCap 600 over the Russell 2000 by showing the cumulative growth of USD 100 from June 1, 1995 to September 29, 2017. The S&P SmallCap 600 would end with a hypothetical value of USD 1,114.38, while the Russell 2000 ends with a hypothetical value of just USD 740.93. Another way to view this is that a market participant would hypothetically return 373% more with the S&P SmallCap 600. Over the period studied, the Russell 1000 slightly outperformed the Russell 2000 and the S&P 500. Since the return of the Russell 1000 was similar to that of the S&P 500, the S&P 500 will be used as the large-cap market benchmark in the analysis. It is also worth noting that the Russell 1000 includes both large- and mid-cap stocks, whereas the S&P 500 is purely a large-cap index.

Another way to measure S&P SmallCap 600 outperformance is by annualized return and risk, as measured by the standard deviation of returns. Since inception, the S&P SmallCap 600 had an annualized return of 11.6% and annualized risk of 18.3%, generating a Sharpe ratio of 0.50.

Over the same time period, the Russell 2000 had an annualized return of 9.6%, annualized risk of 19.2%, and a Sharpe ratio of 0.37. The S&P SmallCap 600’s returns were higher than the Russell 2000 over every time period analyzed, while its risk was lower in every period.

Since the S&P SmallCap 600 was launched in 1994, there are five bear and bull market cycles (as defined by peak to trough and trough to peak periods of the S&P 500) to analyze, and the S&P SmallCap 600 outperformed the Russell 2000 in four of those cycles. From the beginning of the data set on June 1, 1995, through Sept. 1, 2000, small caps underperformed large caps, but the S&P SmallCap 600 returned 129%, which was 15% more than the Russell 2000. In the following bear market, the S&P SmallCap 600 outperformed the Russell 2000 by 15% again. Although the next two cycles returned similarly, the S&P SmallCap 600 has been significantly outperforming in the current bull run since the global financial crisis ended in March 2009, beating the Russell 2000 by 66% and the S&P 500 by 108%. These are compelling returns to argue for a strategic allocation to not just small-cap stocks, but to the S&P SmallCap 600 rather than the Russell 2000.

Lastly, the S&P SmallCap 600 had relatively strong monthly and annual returns compared to the Russell 2000. On a monthly average, the Russell 2000 gained 0.89%, slightly more than the 0.83% gain for the S&P 500, but noticeably less than the average monthly return of 1.03% for the S&P SmallCap 600. Perhaps more important is that the S&P SmallCap 600 also provided downside protection. The down market capture ratio for the S&P SmallCap 600 was just 104.8 versus 119.2 for the Russell 2000. This means for every 1% drop in the S&P 500, the Russell 2000 fell an extra 0.2%. Also, the Russell 2000 fell in 45% of months that the S&P 500 fell, which is slightly worse than the 43% rate for the S&P SmallCap 600.

Referring to Exhibit 5, in any given calendar year for the past 23 years, the S&P SmallCap 600 outperformed the Russell 2000 for at least four months. Only in five years did the S&P SmallCap 600 outperform in less than 6 of the 12 months. On average, the S&P SmallCap 600 outperformed by 1.9% per year. The greatest underperformance of 8.9% occurred in 1999 and

the greatest outperformance of 14.8% occurred in 2000.

performance based on total return in USD. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Table is provided for illustrative purposes.

The performance shown here should at least beg the question of why the S&P SmallCap 600 is not more commonly used as a benchmark. The performance measurement of managers may be held to a higher standard compared with the S&P SmallCap 600. It may bring more credibility to the managers who beat the benchmark, or it could bring to light the managers who might be charging for active management but generating negative alpha.

In the next post of this series, we will show the small cap index performance versus the active small-cap peer group. The results will show the S&P SmallCap 600 could be considered not just as a benchmark replacement, but rather it could more widely serve as the underlying index for investable passive funds.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.