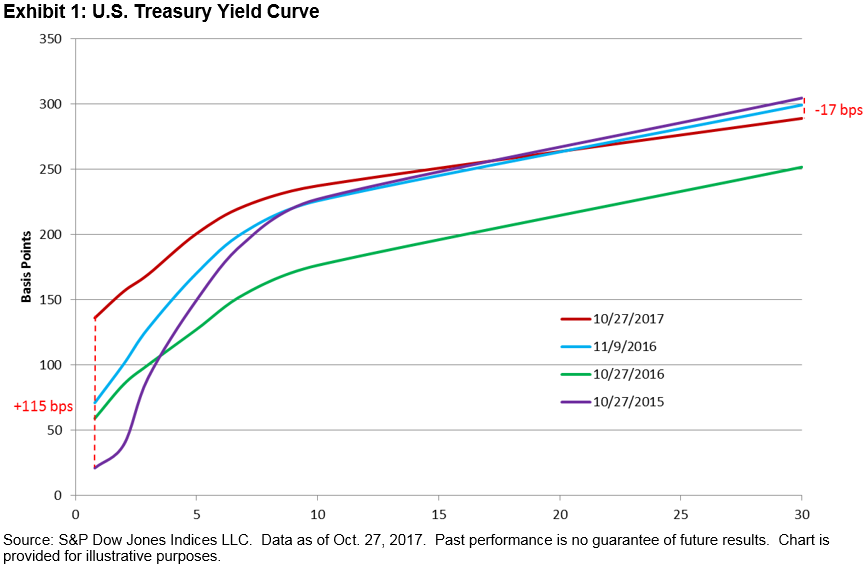

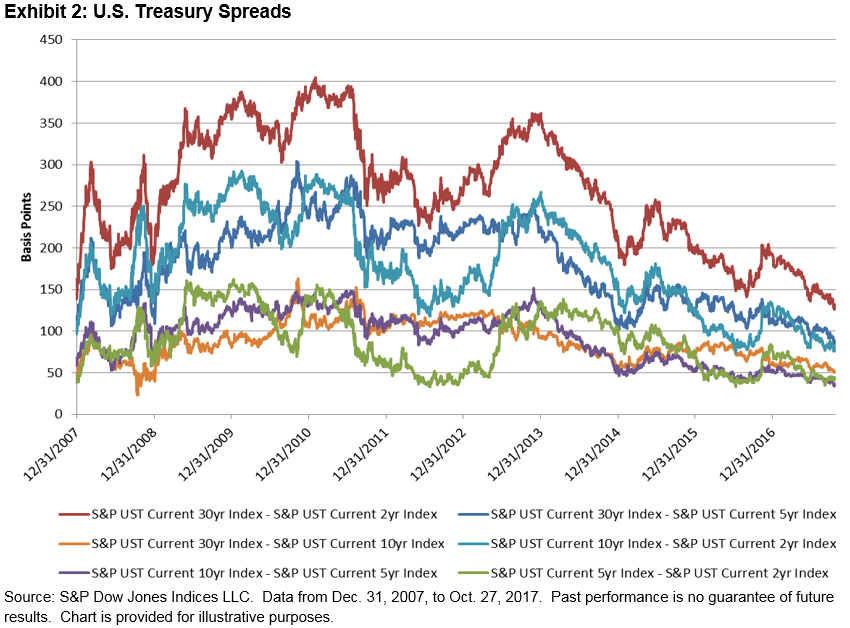

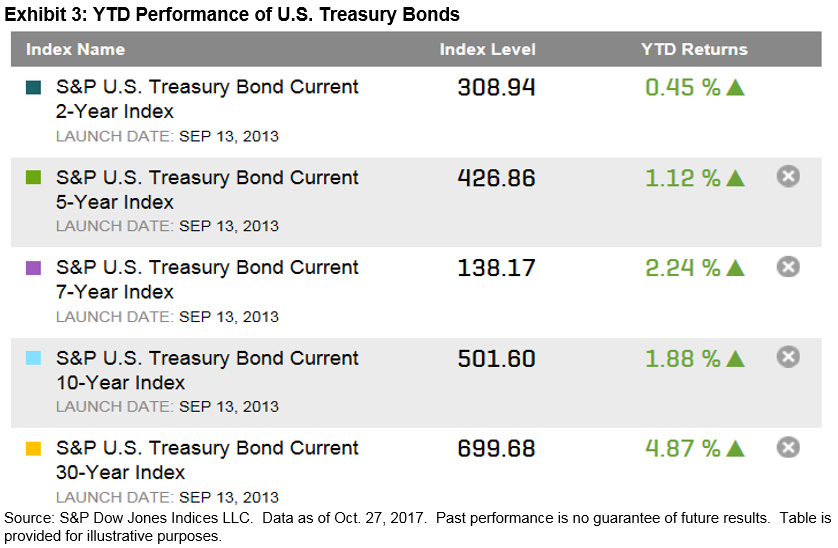

Those looking to convert risky assets into predictable income streams by purchasing bonds or annuities may be disappointed to learn how relatively little income they can acquire with a given level of wealth. However, it is more constructive to accept capital market conditions for what they are rather than looking at this as an insurmountable problem. While low rates equate to expensive income, the other side of the same coin is rich valuation of the stock market (driven by a number of factors but perhaps mainly due to low rates). It is historically rare to have the free lunch of buying relatively cheap income with relatively high-valued stocks. From around 1949 to 1966, capital markets did offer that precise bargain. Stock valuations, as measured by Robert Shiller’s CAPE ratio, increased from between 9-10 in 1949 to a peak of over 24 in early 1966 (see Exhibit 1). The 10-year Treasury rates moved from about 2.30% to about 4.75% over the same period. Those who retired around 1965 who planned ahead and began buying income a little at a time, say 15 years before retirement, would have converted increasingly valued equites into increasingly cheaper (and therefore larger) predictable cash flows.

Unfortunately, free lunches are a rare treat. Most of the time, stock valuations have been high when interest rates were low, and vice versa. For example, in the early 1980s when rates hit all-time highs, the CAPE ratio sank well below 10. You could have bought a lot of income with a given wealth level, but if your wealth was in stocks it was not a great time to sell.

Looking ahead, higher rates may coincide with lower stock valuations. For those approaching retirement, timing income acquisition may be just as fraught as timing stocks. On the other hand, buying expensive income with expensive equities may not be as poor a tradeoff as it first seems—particularly if implemented a little at a time through a methodical program. Dollar cost averaging is a time-tested approach to wealth accumulation; why not apply the same technique to other long-term financial challenges like providing retirement income?

S&P Dow Jones Indices has an index series that represents a strategy of doing just that—dollar cost averaging into assets that mitigate the risk of future inflation-adjusted income. It is called the S&P STRIDE Index Series, but the strategy it measures is not the only way to accomplish the same goal. Bond laddering is another, and there are insurance-based solutions like annuities and guaranteed minimum withdrawal programs. For 401(k) savers, laddering is not feasible and insurance products are not widely available. However, many retirement plan sponsors are actively looking for solutions to facilitate an income goal as the ultimate mission of their plans. If you are fortunate enough to have a retirement plan, that is half the battle. If you have a plan but do not have income options, speak to your benefits department to encourage them to begin considering how to offer a retirement income program within the plan.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.