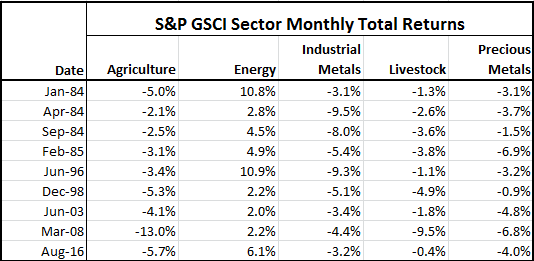

For the first time since March 2008, energy was the only positive sector in the S&P GSCI for the month in Aug. Energy gained 6.2%, while agriculture, industrial metals, livestock and precious metals lost 5.7%, 3.2%, 0.4% and -4.0%, respectively. Not only is this the first month in over 8 years for energy to rise alone, but it has only happened 9 times since energy entered the index in Jan. 1983.

Historically, when energy rises, other sectors rise. In 75% of the time, at least two other sectors rise, and on average gain 93 basis points. The sector performance, especially energy, has great influence on the overall returns of indices with different weights like the S&P GSCI that is world production weighted and the equally weighted Dow Jones Commodity Index (DJCI). For example, it made the difference between being positive or negative for the month with the S&P GSCI gaining 1.8% and the DJCI losing 1.7% in August.

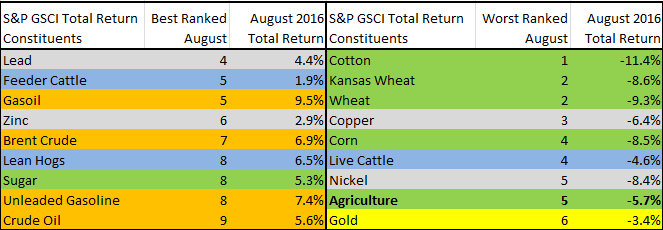

Although energy was the only positive sector, the individual commodity performance was dispersed. Almost half (11/24) were positive with at least two positive commodities from each sector, except precious metals that only includes gold and silver. Gasoil gained 9.5% in Aug. and was the best performer while the worst performer was cotton that lost 11.4%, breaking a new record for its worst August ever with data since Jan. 1977. That was in-line with most of the agriculture sector that was down, posting its 5th worst August ever. However, there was dispersion even inside the agricultural bloodbath, like from sugar. It gained 5.3% in Aug., that was its 8th best August in history from 1973. and its best 12-months in 5 years, up 71.6%.

The split performance shows how the fundamentals impact individual commodities and sectors separately. For example, while it seems oil is having major ups and downs, its volatility is only just over 35% that is slightly above its long-term average. In reality oil’s 90-day volatility has dropped from almost 60% in April to under 40% now, and is less than half its peak from the global financial crisis. Its moves are more controlled now and reflecting its fundamentals. Crude oil has had a total return of almost 40% since January when the suppliers have started to adjust. Since there are issues with OPEC’s ability to control the supply, the key for recovery is lower US inventories. Volatility has also been about 1/3 less this year for metals and agriculture than in their 10-year histories.

Industrial metal commodity returns have had a big divide too. Copper lost 6.4% in August, driving it down 1.9% for the year while zinc is up another 2.9% for the month bringing its year-to-date gains to 42.6%. Zinc is now on pace to post its 3rd best year ever, only behind 2006 and 2009, using data from 1991. There have been supply cuts of zinc that may not be reversed until the companies feel they can produce again at sustainably higher prices. A similar story is true even for aluminum that is generally so abundant. However, the industrial metals as a sector are most sensitive to a weaker US dollar so if the dollar falls, that could be a big positive for the metals.

The Agriculture sector has been reacting as per its individual acreage and crop numbers. Its pricing is dependent mainly on the weather impacts and the commercial processor demand. For example, heavy rain has slowed sugar output, that has boosted prices; whereas cocoa prices increased from a drought.

Our 10th Annual Commodities Seminar takes place in London on 29th September. Additional information and registration are available online now. #SPDJICommods

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.