Negative interest rates – you pay for the privilege of keeping your money in the bank – are current monetary policy in Japan and some European countries. Negative interest rates pose questions: Are they here? Why would anyone pay the bank to keep money? Do they make economic sense? Why would a central bank set negative interest rates? Most importantly, should a central bank make negative interest rates its policy? In what follows, we try to answer some of these.

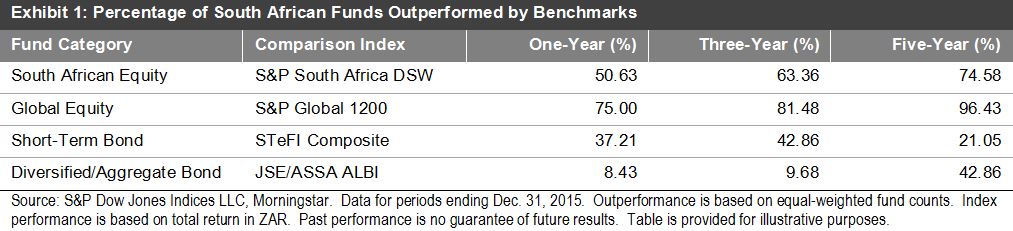

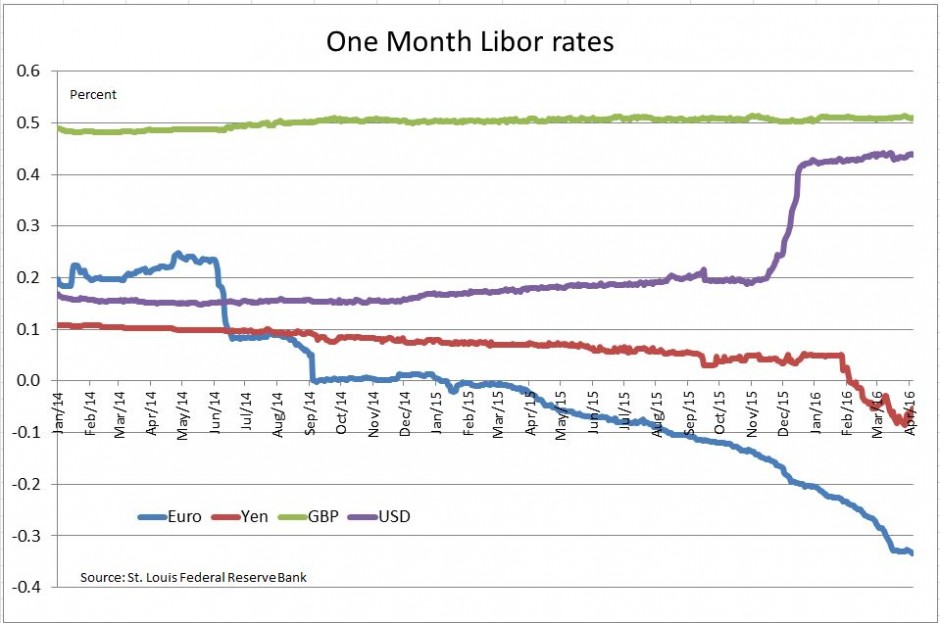

Are they here? Yes, in Japan and in various European countries some short term interest rates are negative. The chart shows one month Libor for the yen, euros, British pounds and US dollars. In most cases only short term interest rates are negative, longer term rates remain positive. Moreover, in most countries the negative interest rates apply to funds that commercial banks keep on deposit at the central banks; in only a few cases do businesses or consumers face negative interest rates on bank deposits. As shown on the chart, typical figures are measured in basis points.

Why would someone pay negative rates? There are convenience and security factors that outweigh the interest cost when rates are very low. Transactions using credit or debit cards, electronic funds transfers or checks are cheaper and easier than using cash. If a business decides that short term cash should really be cash, not bank deposits, they will need a large vault to hold the cash and lots of security to keep holding it. All this costs money so paying 10, 20 or 30 basis points annually to a bank for providing payment services and security is worthwhile. At some point hoarding does become preferable to a bank account,

Do negative interest rates make economic sense? Somewhat. Start with the natural, not negative, rate of interest. When the economy is in a sweet spot with inflation and unemployment are at desirable levels and are not being pushed up or down, the rate of interest is the natural or steady state interest rate. If inflation were close to 2% and unemployment were between 4% and 5% — both roughly the Fed’s targets — and both are stable, then the Fed funds rate would be close to the natural rate of interest. Were an economy is in a slump, businesses weren’t borrowing or investing, people were saving instead of spending then the natural rate would be low or possibly negative. Similarly with a booming economy, businesses and consumers are borrowing and investing or buying and the natural rate is high. When the Fed funds rate is less than the natural rate, monetary policy stimulates the economy, and vice-versa.

Why would a central bank set negative interest rates? In a slumping economy, the central bank needs to push its policy rate below the natural rate of interest for stimulative monetary policy. If the natural rate is below zero, the central bank must push rates into negative territory. The expected result is to encourage banks to lend, businesses and consumers to invest or spend while weakening the currency to boost exports.

Most importantly, should a central bank make negative interest rates its policy? The economic arguments supporting the expected result of negative interest rates appear sensible, but the things don’t always work out. First, FX rates don’t always follow the program – lately the yen and the euro have strengthened against the dollar eliminating one part of the hoped-for stimulus. Second, negative interest rates may be perceived as a panic move, a last chance as the central bank runs out of options. If that happens, businesses and consumers will hoard what they have instead of spending. Third, in many cases the negative interest rates apply only to banks’ excess reserves on deposit at the central bank, so there is no stimulus directly applied to businesses and consumers. Further, this leaves banks with a difficult choice: be pressured to makes loans that may not meet their credit standards or have their earnings squeezed. Either way this may not be the best policy for a central bank.

Negative interest rate might be reasonable short term stimulus, but they are likely to wear out their welcome quickly.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.