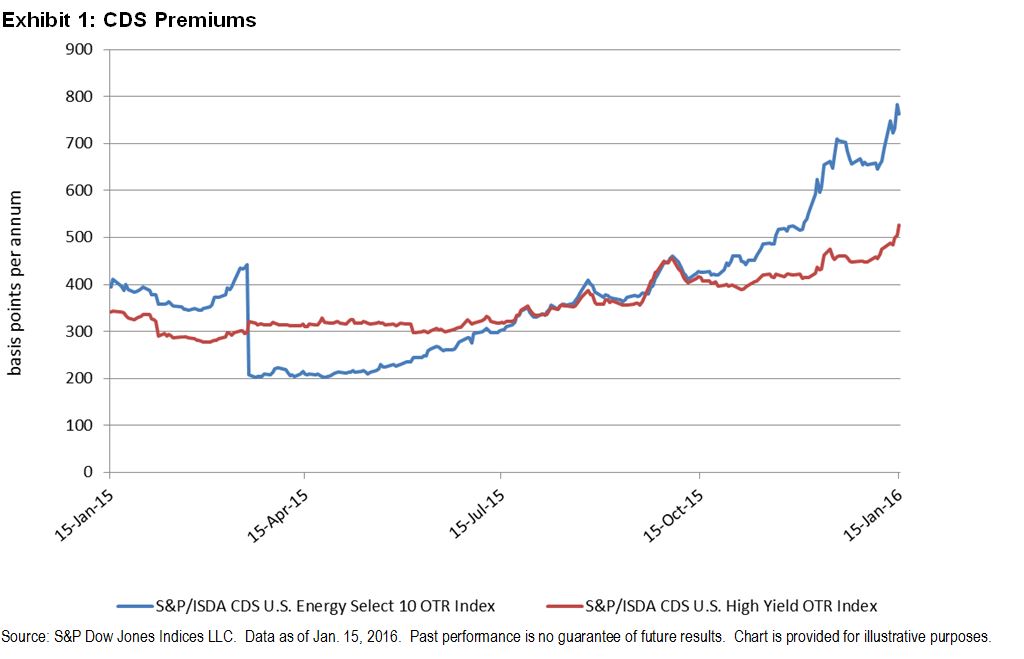

With oil prices at 12-year lows, drivers are spending less money to fill their tanks. However, investors looking to insure themselves against the default risk of energy bonds are being asked to pay up. Rapidly decreasing oil prices have had a negative impact on the forecast operating cash flows of energy companies. As uncertainty rises, the cost of credit protection (i.e., credit default swaps [CDS]) within the energy sector has skyrocketed, as evidenced by the S&P/ISDA CDS U.S. Energy Select 10 (see Exhibit 1). The index, which seeks to track the performance of a select number of reference entities in the U.S. energy market segment, was up 20% YTD and over 110% for the one-year period as of Jan. 15, 2016. Comparatively, CDS spreads within the energy sector are currently 280 bps wider than those of high-yield U.S. corporate entities, as measured by the S&P/ISDA CDS U.S. High-Yield Index. This is especially noteworthy given the recent fears in the high-yield market.

High-yield bonds offer higher rates of interest, given the higher risk of default, than bonds issued by investment-grade corporations. The S&P/ISDA CDS U.S. High-Yield Index is constructed using 80 equally weighted, five-year CDS contracts of the underlying reference entities.

While there is a strong correlation between CDS spreads and deteriorating credit, CDS spreads act more as a measure of the perceived risk of the underlying bond. CDS spreads also depend on other factors such as market liquidity, counterparty risk, and interest rates. It’s also worth mentioning that CDS buyers can seek insurance for credit events other than default. For example, contracts can be written that protect investors against a credit downgrade from investment grade to below investment grade or “junk” status.

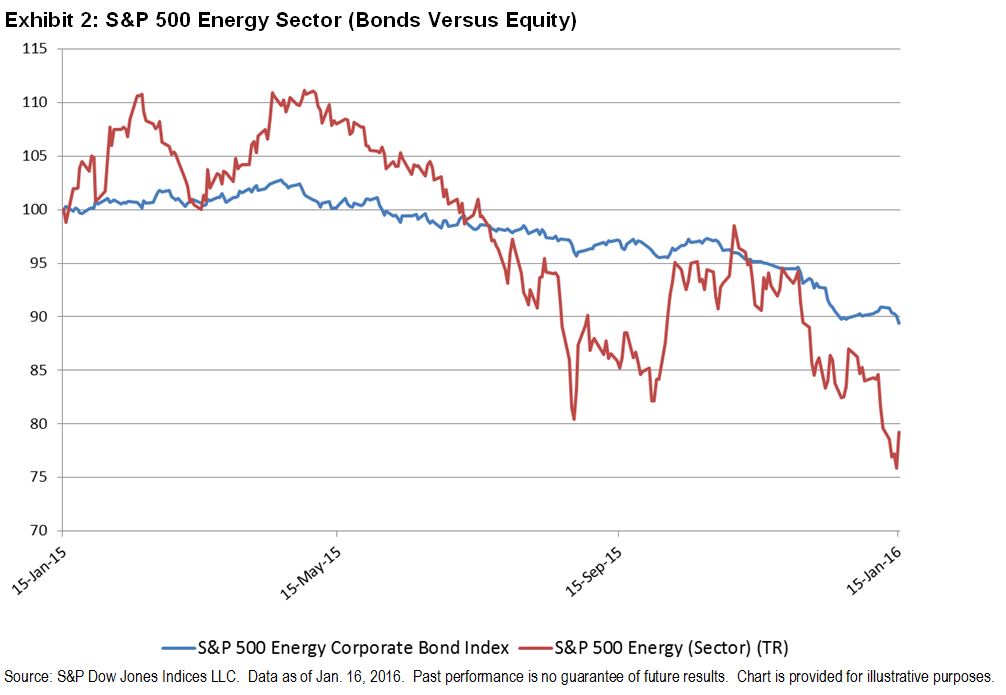

Looking further within the energy sector of the S&P 500®, performance of bonds and equity can be compared using the S&P 500 Energy Corporate Bond Index (TR) and the S&P 500 Energy (TR). While the S&P 500 Energy Corporate Bond Index (TR) was down 10% over the one-year period, the YTD performance was fairly flat. The S&P 500 Energy (TR), however, was down 24% and 6% across the same time horizons, respectively.

Why the difference? Also, why are bond prices not falling as CDS spreads spike? It’s a great example of how the equity, bond, and CDS markets react to information and price risk differently. Between the CDS and bond markets, historically speaking, CDS spreads tend to lead, and sometimes by a significant length of time.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.