Several Fed policy-makers are focusing their comments and analyses on the neutral rate of interest – a level of the real (inflation-adjusted) Fed funds rate that will neither slow down nor speed up the economy. If the Fed funds were set at this level, inflation and unemployment would be stable. The neutral rate changes depending on economic conditions and is ultimately unknown. Despite the measurement problems, it is useful in setting and evaluating monetary policy.

While the neutral rate idea has appeared recently, it is close to an older concept of a natural interest rate due to the Swedish economist, Knut Wicksell (1851-1926). Today’s approach focuses on how the neutral rate changes as the economy adjusts.

The neutral rate is a benchmark for judging the stance of monetary policy. When the real Fed funds rate is lower than the neutral rate, monetary policy is accommodative and will lead to lower unemployment, faster growth and increased inflation; if the real Fed funds rate is above the neutral rate, the reverse trends will be in place. While we don’t know exactly what the neutral rate is today, we do know how it changes as the economic and financial conditions evolve. Combined with an understanding of how accommodative or restrictive monetary policy presently, we can judge how policy should adjust. These ideas, along with current data, are behind the arguments for an increase in the Fed funds Rate, possibly as soon as December 16th, a couple of weeks away.

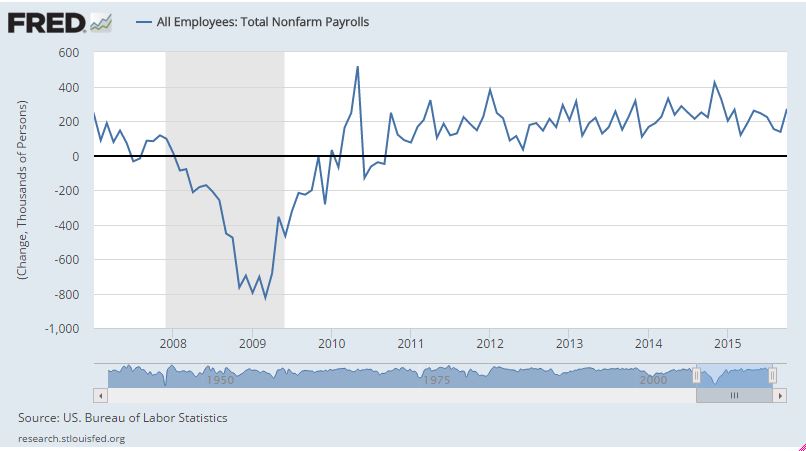

In a recession with employment and inflation falling, pessimistic expectations of the future and few short term investment opportunities, the economy has very little momentum. Even relatively modest interest rate levels may dampen economic activity. In this situation the neutral rate will be quite low. During the last recession in 2007-2009, the neutral rate was zero or less; in Europe today the recent action of the European Central Bank suggests it is close to zero. As economic growth resumes in a recovery and as pessimism shifts to neutral and then to optimism, the neutral rate will rise. If the recovery progresses, increased demand for credit and rising investment will push the neutral rate higher. In a recession, the central bank will seek to keep the Fed funds rate below the neutral rate to support the economy. As the economy improves and the neutral rate rises, the central bank either lifts the Fed funds target to follow the neutral rate up or risks a much too simulative policy position and inflation. How far the real Fed funds rate is above or below the neutral rate affects how aggressive the policy is.

When the real Fed funds rate is close to the neutral rate, monetary policy will gradually move the economy; when spread widens the impact of monetary policy increases. The large rate moves in the early days of the financial crisis and the extremely high interest rates in the 1979-82 inflation wars are examples. Today, there is no room to lower the Fed funds rate; even if the Fed raises its target later this month there will be a little room. But there is plenty of upside – if inflation were suddenly a worry the central bank could easily boost the Fed funds target well above the neutral rate. The importance of this is the asymmetry of risks: keeping interest rates a bit too low buys insurance against unexpected slowness in the economy. Rushing to raise interest rates in fear of inflation makes little sense since there is plenty of upside if tighter policies are suddenly needed.

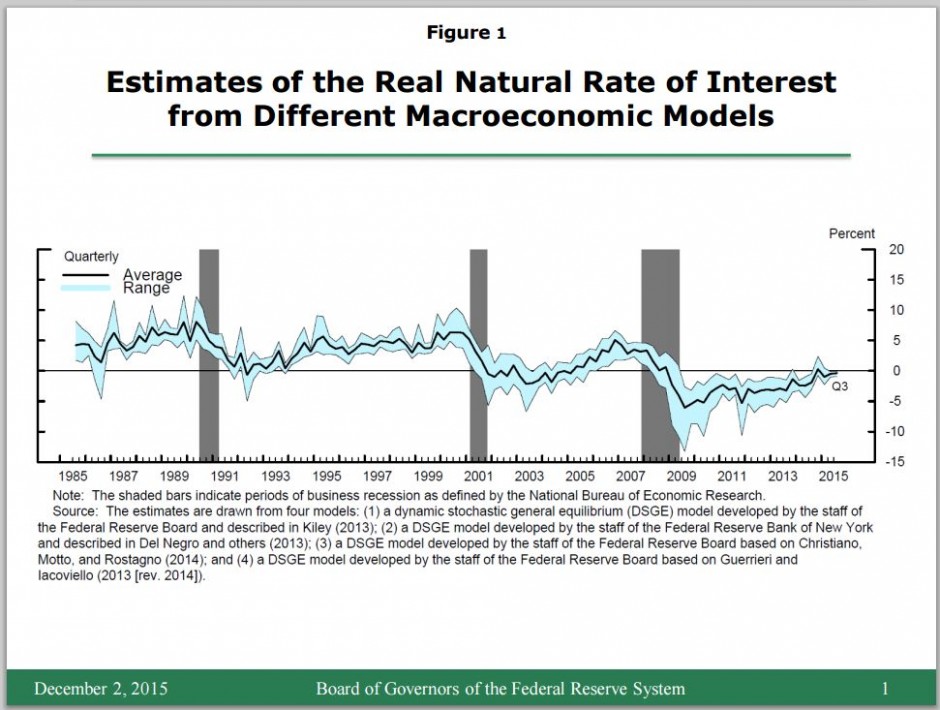

That no one knows precisely where the neutral rate is hasn’t stopped people from estimating its position. The chart from a recent speech by Fed Chair Janet Yellen shows four estimates of the neutral rate.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.