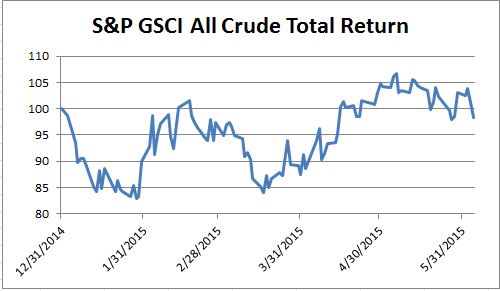

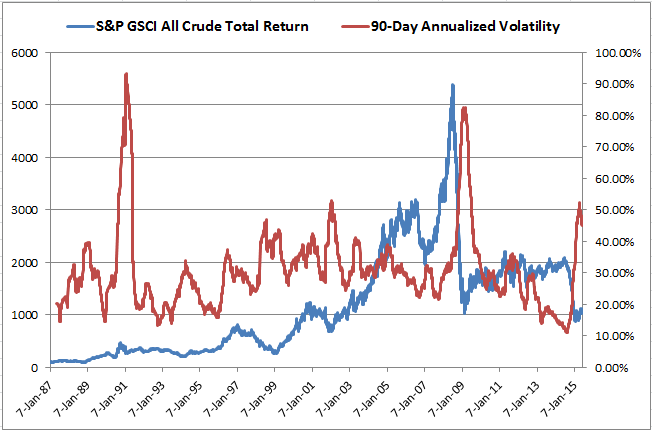

In light of the decision by OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) to maintain its 30 million barrel-a-day production level, the S&P GSCI All Crude lost 4.5% this week, bringing its year-to-date return down to -1.7%, back into negative territory. A status the index has not been able to maintain for more than 3 consecutive days since April 10 – that was 40 days ago.

Chart 1

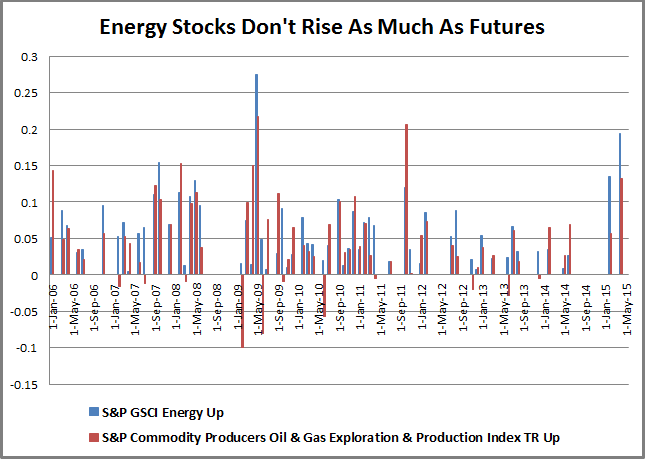

This is evidence of the volatility that oil is experiencing right now, as you can see in the chart below. While today’s volatility is not the highest in history, it is now more than 45% – that is significantly higher than the historical average of about 30%. At this level, it appears, the volatility is too much for investors to bear, so managers are cutting their bets. Will this drive oil prices even lower than the OPEC supply itself?

Chart 2

The price formation of oil is dependent on volatility as the market tries to stabilize. What happens as OPEC continues to flood the market from a pure supply and demand standpoint is fairly obvious. Total supply increases, and until production is reduced enough from non-OPEC suppliers and inventories are drawn down or demand increases, the oil price most likely drops. However, the speculators play an extremely important role in production decisions impacting oil supply.

As Hilary Till pointed out in a comment to the FT, the role of a speculator has been debated for decades. Two of the most well-known research papers on the subject come from Paul Cootner of MIT and Holbrook Working of Stanford in the 1950’s and 60’s. The result of their research says everyone who hedges is a speculator but the risk taking is more specific to different market participants. For example, a producer does not eliminate his risk in the futures market but creates a basis risk that is the difference between the spot and futures price which is more predictable to manage. This is important since it allows the producer to hold more inventories than would otherwise be possible.

The above explanation is precisely why OPEC’s decision to continue to produce oil can backfire and spike the oil price. One more time, WHY?

As production stays high, the oil price drops, the volatility picks up so investors pull out. If investors pull out, then the oil price might drop more, right? WRONG!

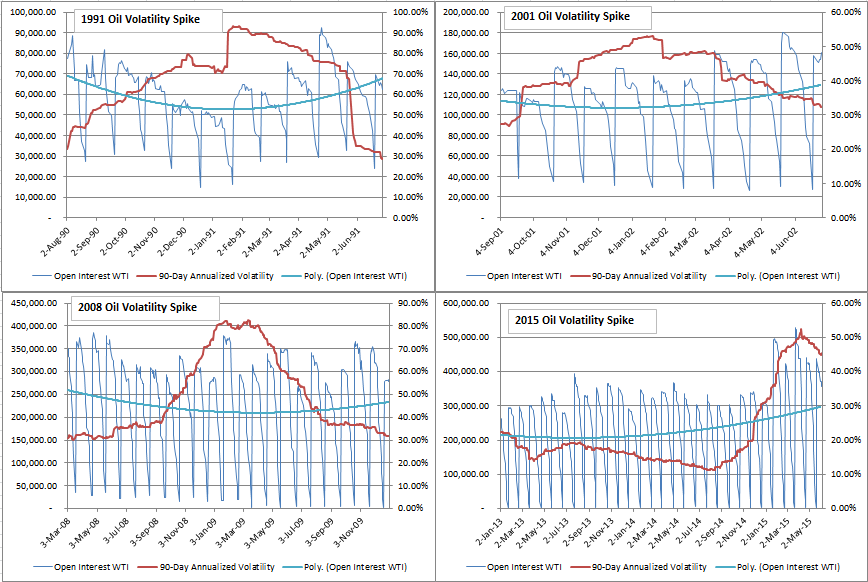

The supply and demand should be unaffected by commodity futures investing since there is no physical delivery from commodity futures investing. Remember, though, that speculators play an important role in risk transfer. As the volatility spikes, investors no longer are motivated to take the risk (go long futures contracts) of supplying insurance to the producers (who are short the contracts to protect against oil price drops.) The result is a collapse in open interest as shown in the charts below that compare volatility spikes with open interest (they are time period close ups of the above graph):

Chart 3

From the charts 2 and 3, one can observe that oil price spikes precede high volatility that causes open interest to collapse. Once investors take risk off the table and open interest collapses, then producers are less motivated to produce and store since insurance is more expensive. Then supply diminishes and the problem of low oil price solves itself as demonstrated in chart 2.

Where are we in this cycle? It appears from the 2015 oil volatility in chart 3 that the open interest has not collapsed yet. This means there may be further increased volatility until more money exits the futures market. OPEC’s decision to continue production may accelerate this exodus. When we finally see open interest collapse, then we may find the bottom of oil prices.

Finally, one tidbit that has been pointed out before is that VIX is the performer during this type of environment of high oil volatility, especially post the global financial crisis. Just this month as oil crossed into negative territory, VIX is up 1.6%.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices