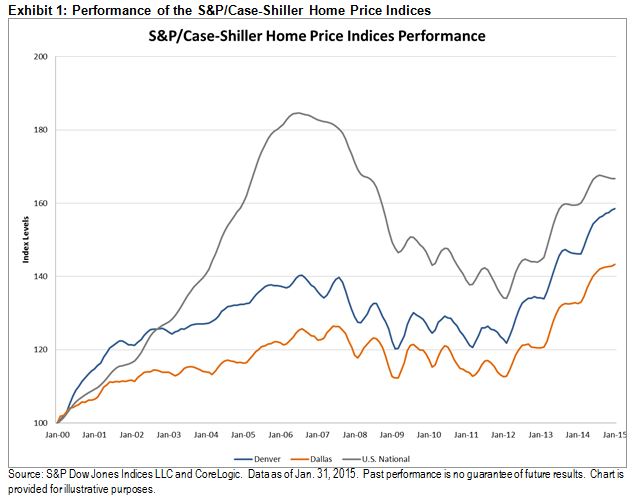

This post examines the relationship between Dallas and Denver, utilizing the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Index for each city. The pair was selected based on a correlation analysis that yielded a correlation coefficient of 0.84 between the two cities. This analysis covered the 20 metropolitan indices in the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Index series, utilized log returns to account for the skewness in the home price data, and spanned a time period of 14 years.

Exhibit 1 depicts the levels of the home price indices for Dallas, Denver, and the entire U.S. For both Dallas and Denver, a trough was felt in February 2009, and the indices are now up 27.7% and 31.8% since that time, respectively (as of Jan. 31, 2015). Both Dallas and Denver have been recording new peaks since the first quarter of 2014.

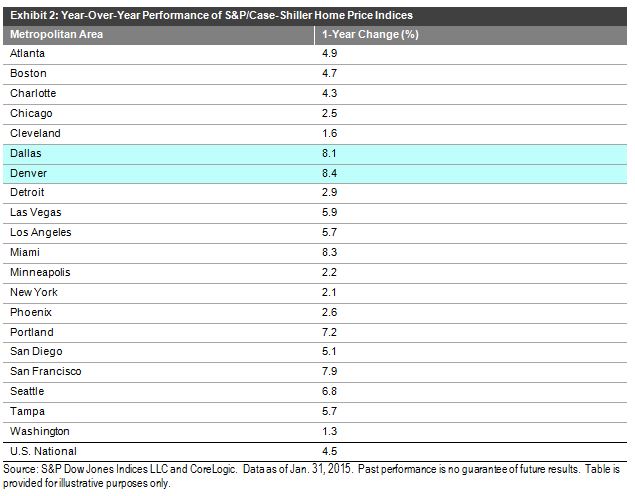

Exhibit 2 summarizes the results for January 2015, showing the year-over-year percent changes. It can be seen that Dallas and Denver are two of the best performers, up 8.1 and 8.4%, respectively.

To attempt to identify drivers that could explain the correlation, we evaluated various housing factors, such as foreclosure rates, housing permits, population change and employment by industry.

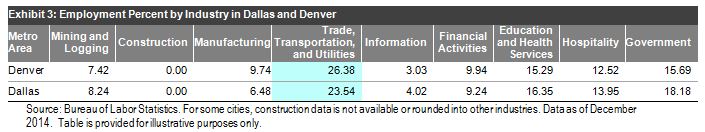

In terms of population change, Dallas and Denver grew at varying rates.1 Dallas lost 30% and Denver lost 29.1% in permit issuance for single-family homes between 2004 and 2013,2 and Denver had a slightly worse foreclosure rate (1.4%) than Dallas(0.4%).3 For employment by industry,4 “Trade, Transportation, and Utilities” was the highest employment industry for Dallas and Denver by a large margin. It should be noted that this industry also had a large allocation from other, uncorrelated metro areas.

These findings led us to explore more theoretical analysis. The energy industry is considered the cornerstone of Dallas and the North Texas economy. Denver, long hailed the Houston of the Rockies, is the largest city in a 600-mile radius of energy companies that are investing in the oil and gas fields of Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, and North and South Dakota.5 Metro Denver and the Northern Colorado region ranked fourth for fossil fuel energy employment, and fifth among the nation’s 50 largest metros for cleantech employment concentration in 2014.6

The energy industry fuels jobs and activity across a range of fields, affecting population, income, and therefore, the housing market. The industry is thus a strong candidate as a reason for what is driving Dallas and Denver’s intertwining performance. It will be interesting to see what the impact of the plunging price of oil on the two cities will be, and if one (or both) will be affected, especially in comparison to the other metropolitan areas.

On a lighter note, and if you are still not convinced that there is a correlation between the two cities, here is a tidbit of information. In 1981, ABC launched a Denver-based, oil tycoon soap opera to compete with the CBS primetime oil company-owning family series Dallas.