Fed watchers will study the FOMC minutes for hints of the next interest rate move. However, the most important data – the January employment report – was published more than a week after the FOMC meeting. That report showed strong job growth not just in January but over the last few months as data revisions presented a clearer picture of the economy. Many Fed watchers seem to be discounting the Employment Report and focusing on low oil prices and declines in the consumer and producer price indices. Recent comments by FOMC members suggest that the era of the zero Fed funds rate could end as soon as June, only four months away.

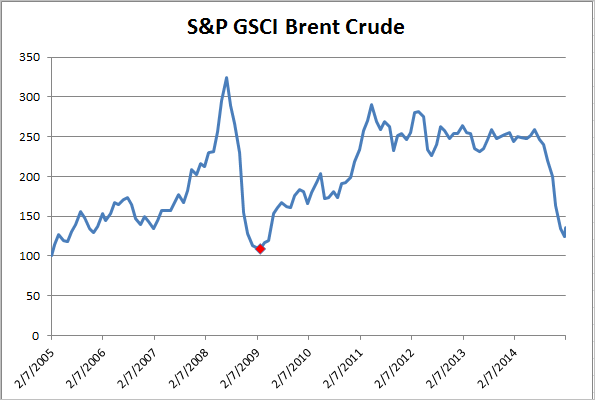

With the unemployment rate at 5.7%, weekly initial unemployment claims running at about 300 thousand per week and payrolls expanding consistently there is no doubt that the economy is enjoying strong growth. The inflation picture is more debatable. The Core CPI – excluding food and energy – is up about 1.5% over the last 12 months and is close enough to the Fed’s 2% goal to support returning interest rates to normal (non-zero) levels. Oil is a question. The price of WTI crude oil made a recent low of $44.45 on January 28th but has now advanced to $52.60 on February 17th. No one knows what oil will do next or when it might rebound to the over-$100 level of last June. However, many US oil producers cannot sustain their business at current prices. There is a growing sense that, sooner or later, oil prices will rise, even if they don’t return to triple digits. When oil prices do rise, they will echo through the economy and boost other prices as well. Both the employment strength and concerns about a possible rebound in oil prices argue for an increase in the Fed funds rate.

Comments from FOMC members since the last meeting in late January point to an early move on interest rates. The data are cited as evidence that the economy is strong and that risks are shifting to more inflation rather than more unemployment. Among those suggesting an early shift to more normal interest rates are Jeffrey Lacker of the Richmond Fed, John Williams of the San Francisco Fed, Loretta Mester of the Cleveland Fed and Esther George of the Kansas City Fed. The FOMC vote count may be more interesting than usual in the last, and next, set of minutes.

Many Fed watchers are expecting, or arguing for, continuing the current policy of close to zero interest rates. While agreeing that the US economy seems strong for the moment, they fear secular stagnation – the idea that potential US economic growth is capped at around 2%, less than the 2.5% to 4% experienced in recent decades. Potential GDP growth can be gauged by the sum of labor force growth plus productivity. Among developed nations the US is one of the few where population is growing, although growth is slowing and the population is aging pointing for slower labor force growth. Recent labor force growth is under one percent and productivity is about three-quarters of one percent giving potential GDP growth of 1.75%. The argument is that if potential growth is this low, now is not the time to slow down the economy or dampen employment gains.

The FOMC members may be more concerned with near term risks that economic strength could run into rebounding oil prices and raise inflation expectations. And the members are the people who make the rate decisions.

The FOMC minutes will be released at about 2 PM on Wednesday February 18th

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.