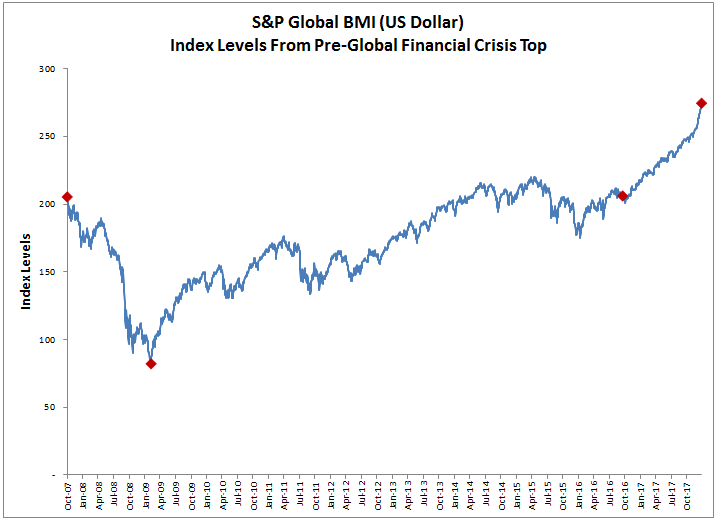

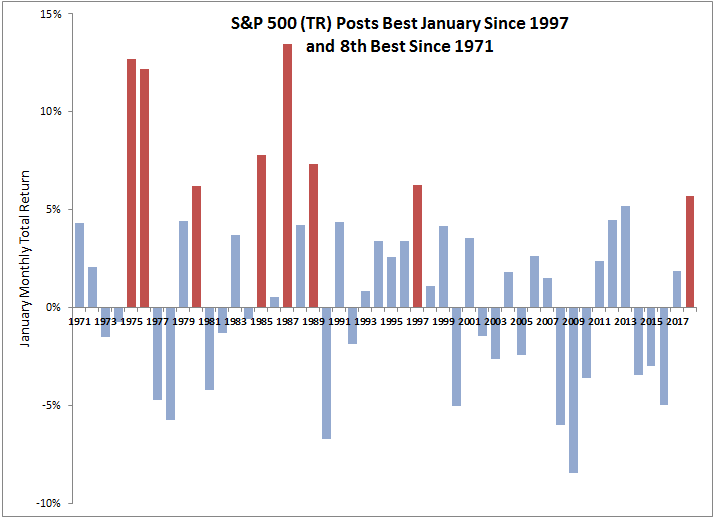

If the glass can be more than half full, this stock market glass is so full, it’s time to wonder when it may spill over. Large-caps continue to lead the U.S. equity market with the S&P 500 (TR) delivering its 15th consecutively positive month, its best month since March 2016, its best January since 1997 and its eighth best January on record, gaining 5.7% (since 1971.)

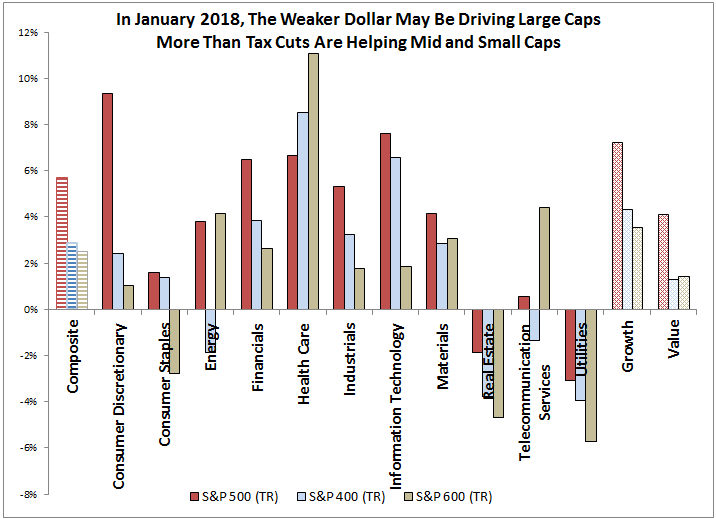

In prior years with January gains this big, all the years ended highly positive with the exception of 1987, which arguably had a structurally different market than today. While 1995 was the best year on record with a gain of 37.6%, its January that gained 2.6% was not quite as strong as in 2018. However, the 2nd, 3rd and 4th best years are all on the list with other very high ranking years too.

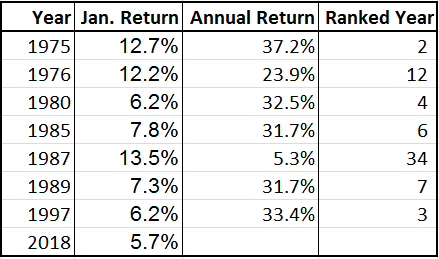

The market is excited to say the least. In a measure of optimism by the outperformance of the S&P 500 versus the S&P 500 Bond Index, the stocks are outperforming by the most, 6.6%, since October 2015, when the outperformance was 7.9%. Also, the consumer discretionary sector showed its greatest optimism with a premium of 10.1%, the 7th most in history, and the most since Sep. 2010, when its premium was 10.5%. This is supported by the tax cuts and the increased consumer confidence of 125.4 (1985=100), up from 123.1 in December, as reported by the Conference Board. Though the glass looked more than half full for the health care sector in January that posted its biggest premium since January 2013, that glass may be starting to empty from the push to cut health care costs. It may not be the only sector starting to look half empty as real estate and utilities are both measuring discounts for the second consecutive month. Though a few of these glasses are looking half empty most seem still very full. If the S&P 500 Bond Index starts outperforming its more famous stock counterpart, the S&P 500, it could be a warning sign. Immediately following that high premium in October 2015, the stock market topped on Nov. 3, 2015, and by December investors saw the glass as half empty. The exuberant premium turned into a discount, and in the following period through Feb. 11, 2016, the market dropped 12.7%.

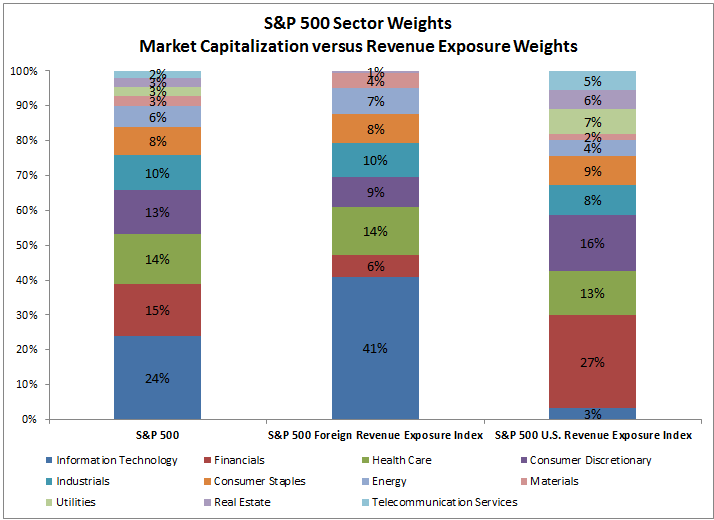

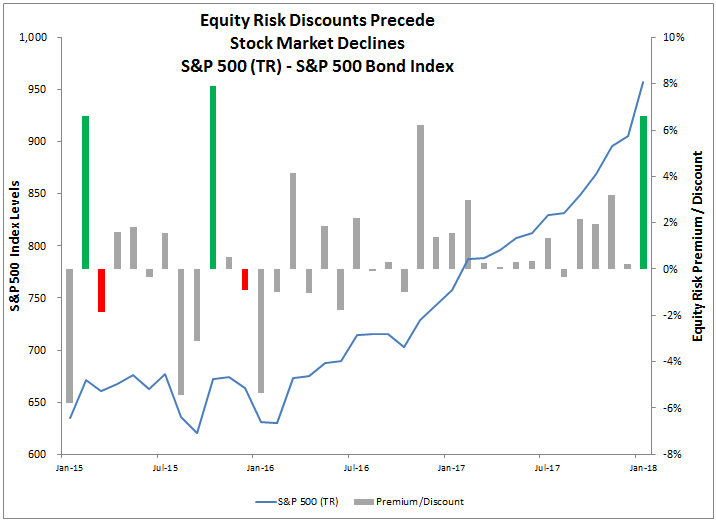

In other segments of the U.S. equity market, the performance continued to be strong in January. The S&P SmallCap 600 (TR) returned 2.5% and the S&P MidCap 400 (TR) gained 2.9%. While consumer discretionary led large caps, gaining 9.3%, its best month since Oct. 2011, health care led small-caps, gaining 11.1%, the most since Sep. 2010, and mid-caps, gaining 8.5%, its best month since Jan. 2012. The large cap consumer discretionary sector may not be only benefiting from the tax cuts and high consumer confidence but from the international business boost from the weaker dollar. In the health care sector, where so much business is domestic for smaller and mid cap companies the tax cuts may mean more for them, helping them outperform the larger part of their sectors. Together with health care and consumer discretionary, financials, industrials, information technology and materials gained regardless of size. Smaller consumer staple companies have been challenged with changing consumer tastes for food with higher demand for whole and raw ingredients. Mid-cap energy companies also underperformed the big and small parts of the sector as they may not have been able to benefit as much from international business as the large caps but may have also been more hedged and less nimble than small caps as oil rebounded and the dollar fell. Real estate and utilities are suffering from falling bond prices and rising yields from more inflation fears after the passage of the tax cuts. Large-caps are outperforming mid-caps by 2.9%, the most since Sep. 2014 and are outperforming small caps by 3.2%, the most since May 2017.

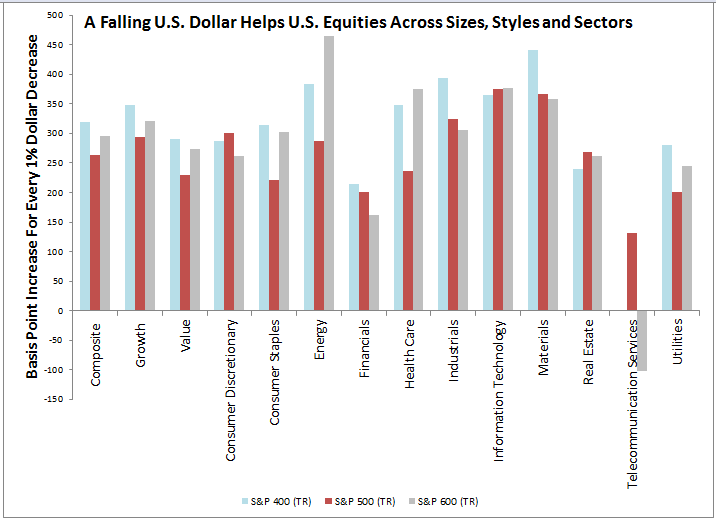

The weaker dollar seems to be winning over the tax cuts in lifting large caps beyond the mid and small size companies, though on average the falling dollar helps mid-caps most. Energy and materials gain most from a falling dollar since the natural resources are priced in dollars. Although large-caps do most international business, the falling dollar may present growth opportunities for mid-caps that otherwise might not do as much international business. If the dollar continues to fall, energy, materials, information technology, industrials and consumer discretionary may be where to overweight, as well as in mid-caps and growth.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.