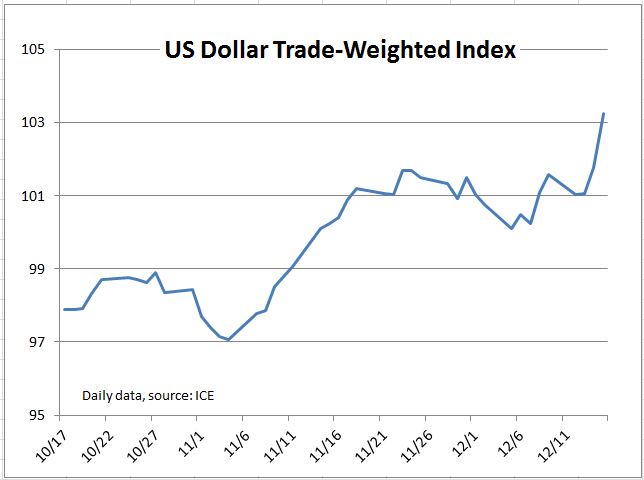

The US dollar continues to advance against most developed market currencies as analysts point to rising US interest rates and expectations of tax cuts and increased federal spending as reasons to expect further gains.

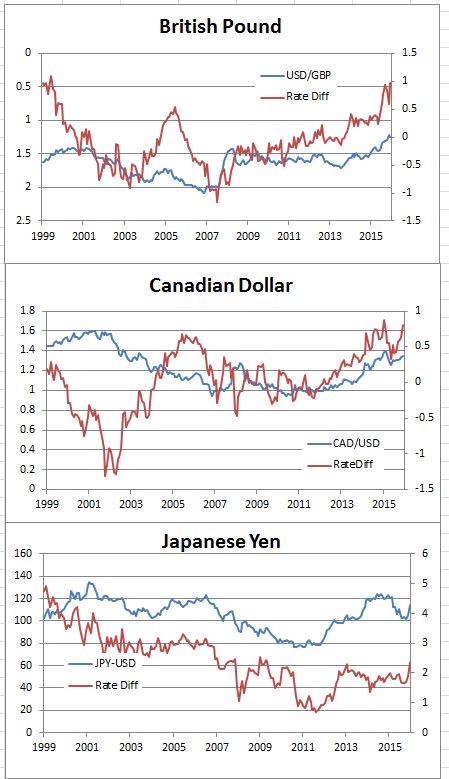

One might expect investors to shift their fixed income investments to markets with higher interest rates. Since rates are currently higher in the US than the UK, Japan or Canada, this might be a reason to expect the US dollar to appreciate against those other currencies. The charts compare the difference between the US ten year treasury yield and the yields on British, Canadian or Japanese rates with the forex value of those currencies against the dollar. The charts suggest that interest rate spreads do have some relation to foreign exchange rates. However, the linkage is not strong enough to reliably forecast the forex rates and the charts say nothing about causation – which comes first between interest rates and currency (Note that the line for the British pound against the dollar is inverted so that when both lines rise, the correlation is positive.)

Interest rate differentials aren’t the only factors affecting forex rates. Macroeconomic policy also matters. With the elections, it appears that US fiscal policy will ease substantially as spending increases and taxes are cut. The new administration has argued for higher US interest rates and tighter monetary policy – given yesterday’s move by the Fed, that is likely. The first Reagan administration (1981-85) had tight money, easy fiscal policy and a soaring US dollar.

Forecasting foreign exchange rates is notoriously difficult. There is a long series of academic papers extending back to the 1980s testing forex forecasting models. A random walk model with no economic or financial variables tends to do as well as any of the economic and financial models. One explanation is that forex rates, like most of financial variables, depend on expectations of the future. Back testing a model with realized expectations often gives great results which vanish when the expectations need to be about the future rather than the past.

Even if we can’t accurately forecast foreign exchange rates, we can think about their impact. Having a strong currency may make people feel good about their country; it isn’t always the most desirable economic policy. A strong dollar is good for consumers: cheaper imports and less expensive foreign travel. However, it can hurt exporters whose customers face higher prices in their own currencies. A company deciding between manufacturing at home or abroad may see the strong dollar as a reason to ship jobs overseas. However, policies to push the dollar down can also create problems. A collapsing dollar would mean higher import prices importing inflation. Given complexity and difficulty of trying to forecast or manage the foreign exchange rate, the answer maybe to hope for a currency rate that is roughly right and not too volatile.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.