In the current environment of short-term volatility amid a long-term positive outlook for the Chinese economy, a focus on growing, sustainable dividends in China’s equity markets could provide the opportunity to get a slice of the region’s structural growth and potential downside protection compared with a typical growth strategy, such as an earnings growth strategy.

In recent years, with the release and implementation of a series of dividend-encouraging policies issued by Chinese authorities, the amount of dividends issued by companies listed in China’s equity markets has gradually increased. In 2014, the size of the total dividend pool for companies in the S&P China A BMI was USD 70 billion, nearly triple the size of the dividend pool in 2009. In terms of the number of companies, 70% of the S&P China A BMI universe paid dividends in 2014, which is much higher than the 55% reported in 2009.

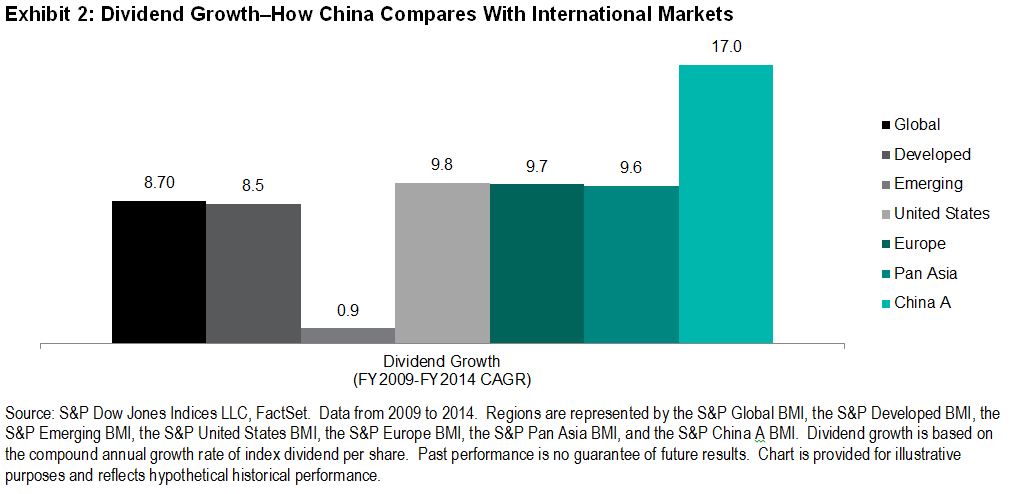

From a dividend growth perspective, Chinese companies may offer much faster dividend growth than companies in many other parts of the world. From 2009 to 2014, Chinese equities provided a dividend growth rate of 17.0% per year, driven mainly by improved earnings—far higher than equities in Pan Asia, Europe, and the U.S.

One unique feature of Chinese companies is that they tend to have more concentrated company ownership, either in the form of a founding family or a government-affiliated entity. The implications on dividends are three fold. First, many of China’s IPOs are due to the privatization of large stakes in SOEs and family-run businesses. These are typically mature companies that pay dividends from the beginning of their public listings. This explains the fast growth of dividend pools in China.

Second, dividends may provide a sign of positive corporate governance in China. Under the conditions of high concentration of ownership and weak legal protection for small- and medium-sized shareholders in China, the distribution of dividends can be used as a way to limit large shareholders’ ability to expropriate minority shareholders’ rights or improper government intervention in the listed companies.

Third, many of the largest dividend-paying Chinese companies are SOEs with a high degree of direct or indirect government ownership. Therefore, the Chinese government influences companies’ earnings and dividends. Given the government support to improve dividend policies, these companies tend to return a greater share of earnings to shareholders via dividends.

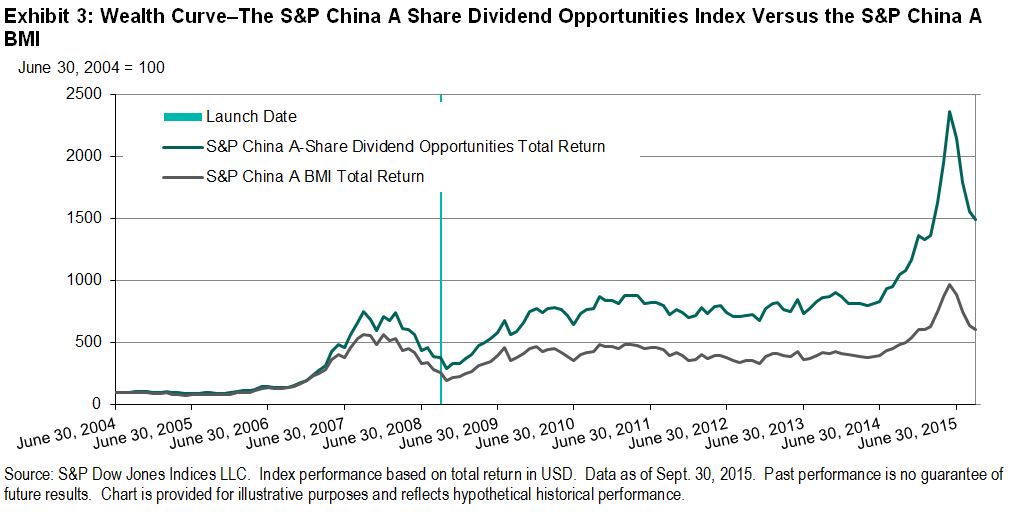

The S&P China A Share Dividend Opportunities Index seeks to offer a transparent, rules-based, diversified, and tradable strategy for investors looking for exposure to China’s growth via dividends. The index seeks to measure high-yielding A share stocks traded on the Shanghai or Shenzhen Stock Exchanges. The index was launched on Sept. 11, 2008, showing a seven-year live track record of consistent outperformance against the benchmark, the S&P China A BMI (see Exhibit 3). The index may be attractive to investors for its total return, income generation, and potential for downside protection. For more information, please refer to the following research paper by clicking here.