In our previous blog (part II), we introduced SPACs’ lifecycles, as well as the potential benefits and risks of investing in SPACs. In this blog, we will focus on SPACs’ liquidity. In general SPACs’ liquidity is poor when seeking the target, surges on the deal announcement date, and remains low relative to the S&P SmallCap 600® after de-SPAC.

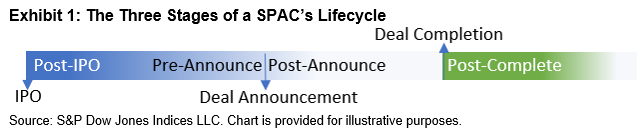

As of March 26, 2021, the median market capitalization of all listed SPACs was USD 284 million, much lower than the median market capitalization of USD 1.5 billion of S&P SmallCap 600 constituents. Since most SPACs are small- or micro-cap companies, we compared their liquidity against the S&P SmallCap 600. Based on the lifecycle of a SPAC, we analyzed its liquidity in three stages: post-IPO, deal announcement, and post-deal completion (see Exhibit 1).

We analyzed the 767 SPAC IPOs listed on the NYSE, NASDAQ, and NYSE American since 2008. As discussed in part I of our blog series, the majority of SPAC IPOs occurred in 2020 and 2021. We tracked the history of each SPAC through its lifecycle. Of the 767 SPAC IPOs, 27 were liquidated, while 23 SPACs finished the merger but were further acquired by another company, privatized, or became bankrupt. We excluded these 50 SPACs from our analysis in order to focus on the de-SPAC companies before any further corporate actions. Only common stock is included in our analysis.

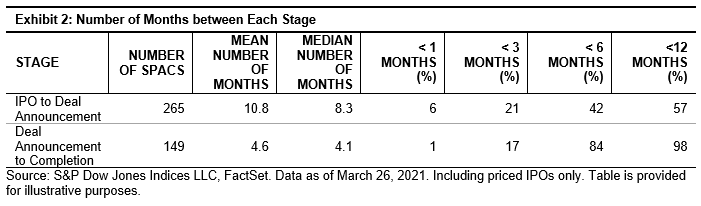

Exhibit 2 shows that the average number of months from IPO to deal announcement was 10.8 months, and the average number of months between deal announcement and deal completion was 4.6 months. 57% of SPACs announced a target within 12 months, and 98% of SPACs completed the merger within 12 months. For our analysis we use 1, 3, and 6 months for post-IPO, and 3, 6, and 12 months for post-completion.

Liquidity

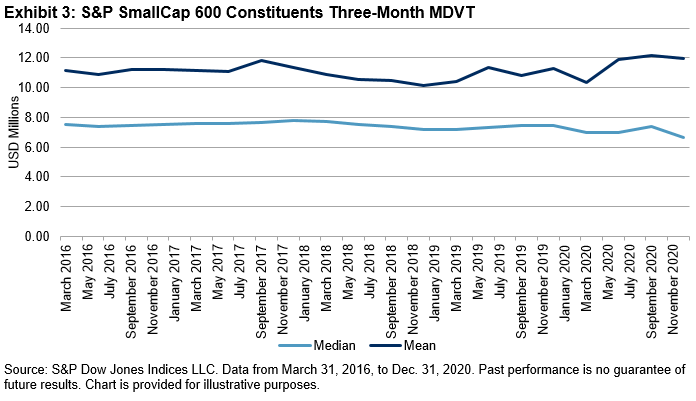

Exhibit 3 shows that the median of the S&P SmallCap 600 constituents’ past three-month median daily value traded (MDVT) was around USD 7 million at each quarter-end during the past five years, and the mean was around USD 11 million.

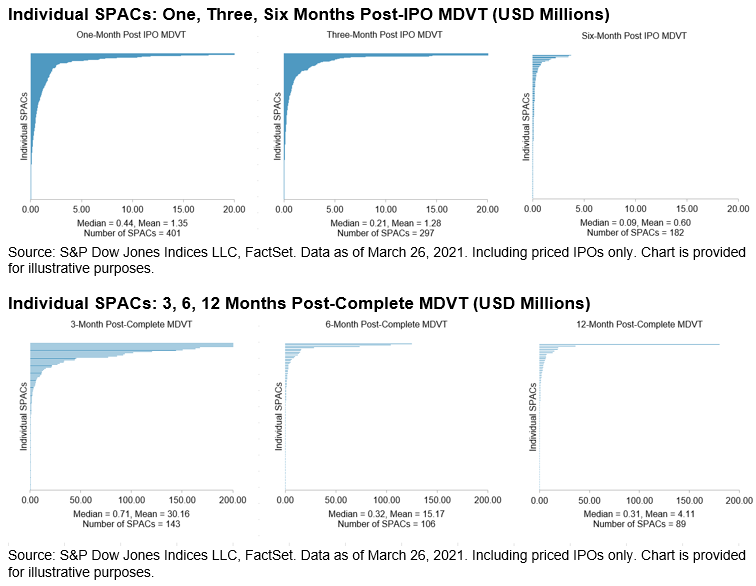

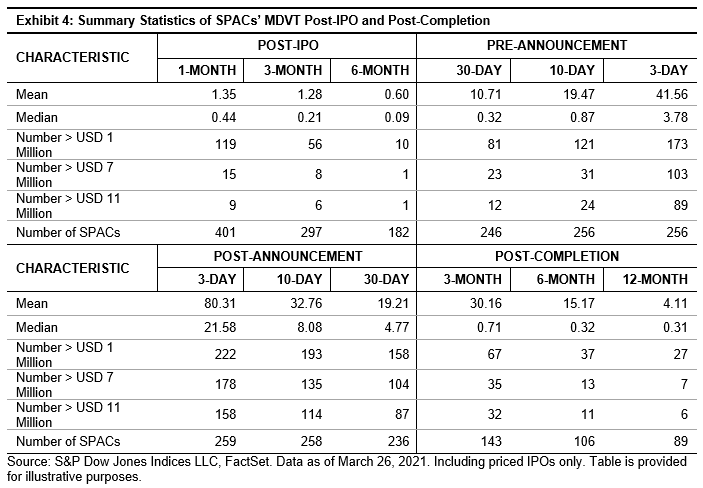

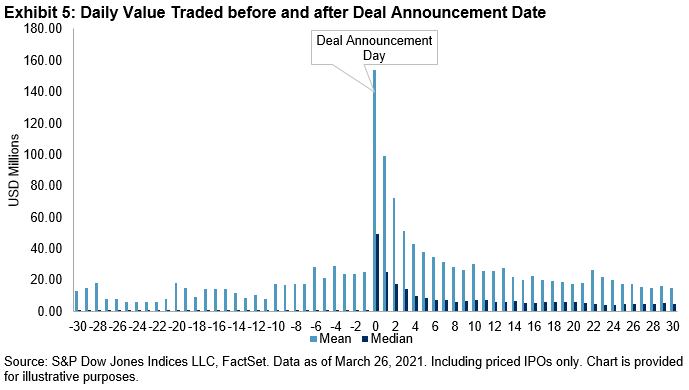

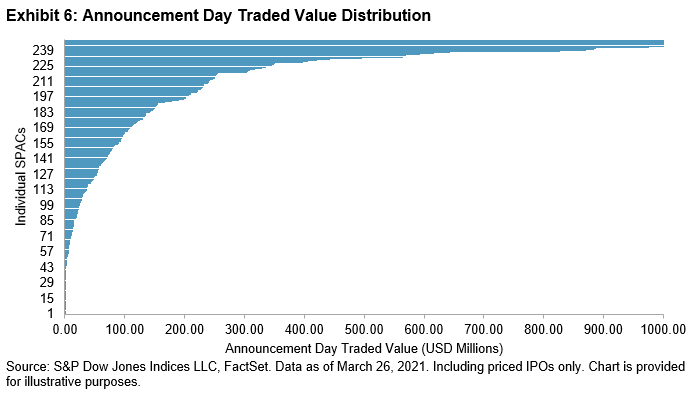

Exhibit 4 summarizes the SPACs’ MDVT and how that compares to the USD 7 million and USD 11 million benchmark liquidity post-IPO and post-completion, respectively. Exhibit 5 shows how the daily value traded changed 30 days before and 30 days after deal announcement, and Exhibit 6 highlights the distribution of value traded on the announcement day. The data shows the following:

- Most of the SPACs’ liquidity was lower than the median liquidity of the S&P SmallCap 600 constituents (see Exhibit 4).

- During their lifecycle, SPACs’ liquidity was the worst when searching for a target (see Exhibit 4). On the day of deal announcement, SPACs’ liquidity tended to improve significantly (see Exhibit 5 and Exhibit 6). Once a SPAC completed the deal, it traded with lower liquidity than the median of the S&P SmallCap 600 constituents (see Exhibit 4).

- At each stage, SPACs’ liquidity decayed rapidly after the corporate action (see Exhibit 4).

- The median liquidity was much lower than the mean liquidity, which shows that the distribution is heavily skewed in each stage (see Exhibit 4 and Appendix).

In our next blog in this series, we will follow the same framework to analyze SPACs’ performance.

Appendix