Our SPIVA® reports have shown, year after year, that market-cap weighted benchmarks are, to put it kindly, hard to beat. However, in 2019 a range of circumstances made “hard to beat” become nigh-on impossible for the S&P 500®.

In general, there are three common ways by which an active portfolio can outperform its benchmark: over or under-weighting benchmark stocks, by tilting towards factors or sectors, or by venturing beyond the benchmark’s constituents to hold anything from cash to commodities. Each of these options was uncommonly disadvantaged last year.

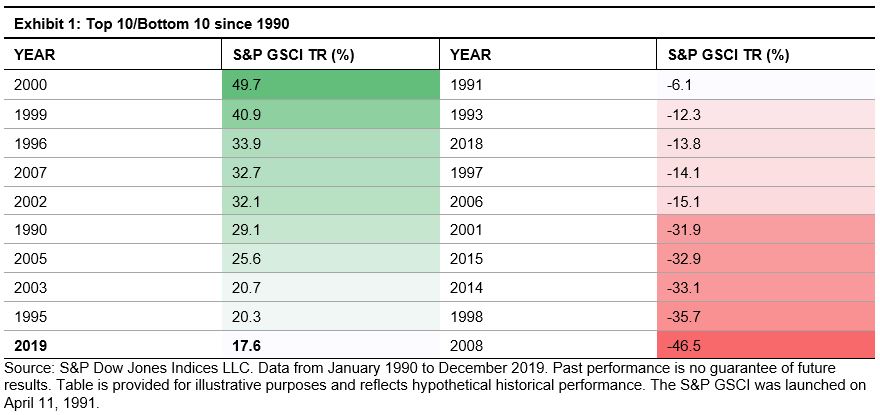

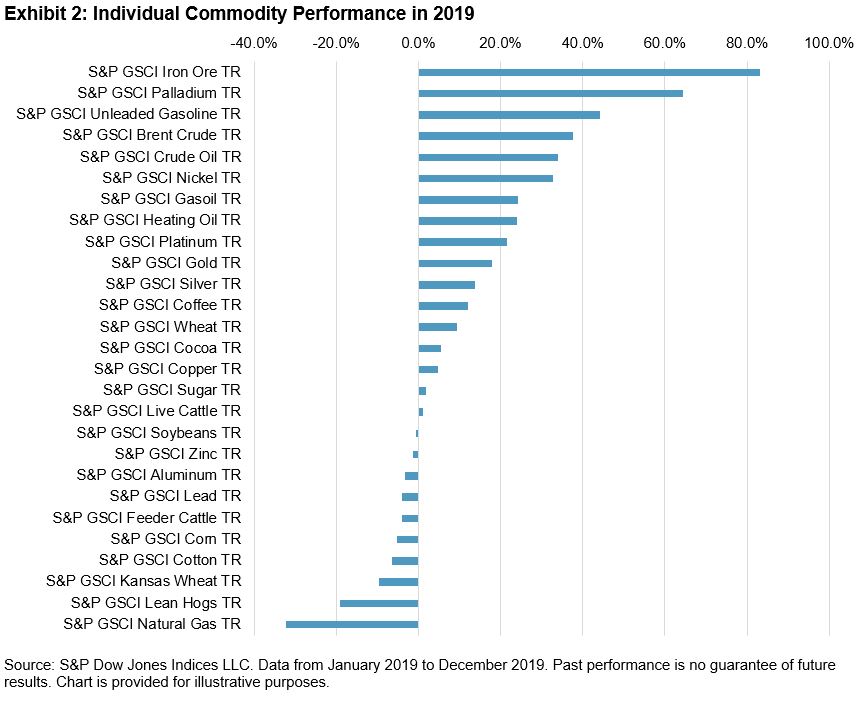

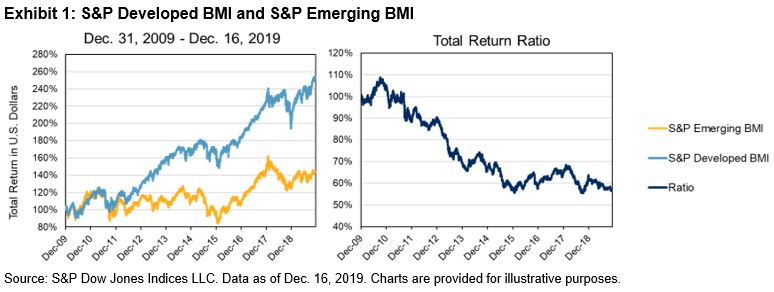

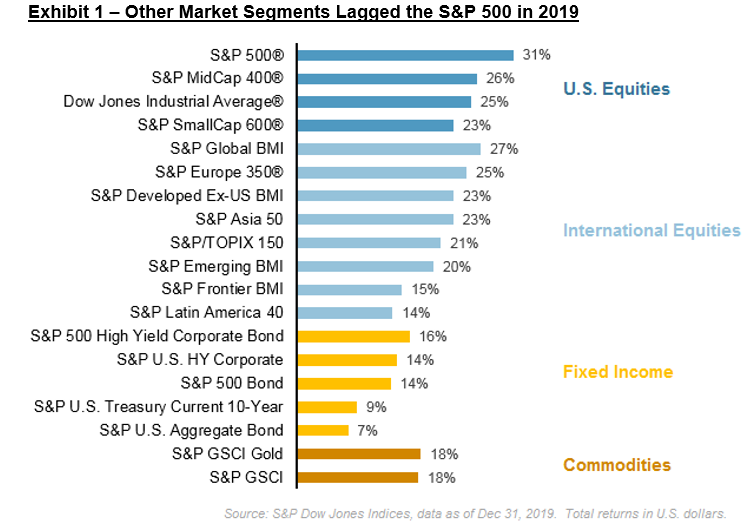

Based on the performance of a wide range of alternative markets, going outside the benchmark was not much help. Smaller U.S. stocks, international equities, fixed income, and commodities all underperformed large-cap U.S. equities.

Stock selection within the benchmark was handicapped by the 51% average gain of the biggest five stocks in the S&P 500. Since few active managers (and few factor indices) allocate as much to the largest companies as the benchmark does, when the very largest stocks outperform, stock selection becomes harder.

Relatedly, the larger sectors of the S&P 500 also outperformed their smaller peers. The Information Technology sector – the largest in the S&P 500 – gained a whopping 50% on the year.

The performance of equal-weight indices provides an easy way to analyse the importance of size in stock and sector selection. S&P 500 Equal Weight Index has the same constituents as the S&P 500, but weights each constituent equally, with the result that the sector allocations are also more balanced. As illustrated in the latest S&P Equal Weight Sectors Dashboard, both underweighting the largest sectors and weighting equally within each sector helped to contribute to the 2.3% underperformance of the S&P 500 Equal Weight index in 2019. In fact, sector allocations were responsible for the lion’s share of underperformance – with an underweight in the tech sector accounting for over 1% of the drag.

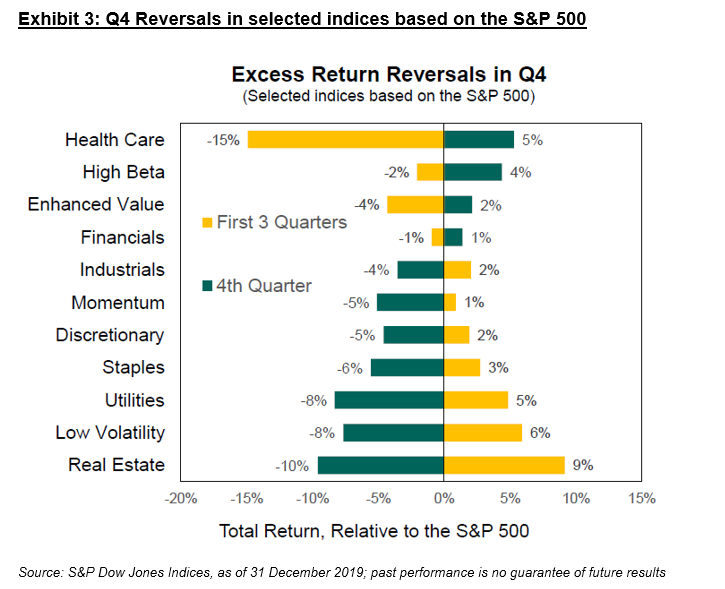

But … some parts of the market must have outperformed? If you didn’t overweight the largest sectors and stocks, the sting in the tail of the market’s performance this year was that, beyond portfolio construction, a degree of timing was also required to maintain outperformance. As we highlighted in our year end S&P 500 Factor Dashboard , for several areas of the market, there were major reversals into the year end: the Health Care sector, for example, underperformed the S&P 500 by 15% in the first three quarters, and then outperformed by 5% in Q4. In September, the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index looked certain to finish the year on top, but failed to keep pace with the fourth quarter’s rally.

What does this mean for active equity managers? Early indications point to a rough year for stock pickers, with less than 1/3 of active U.S. equity managers estimated to have finished 2019 ahead of their benchmarks. Whatever else may be true of the coming year, active managers might at least hope that the S&P 500 goes back to being just “hard” to beat.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.