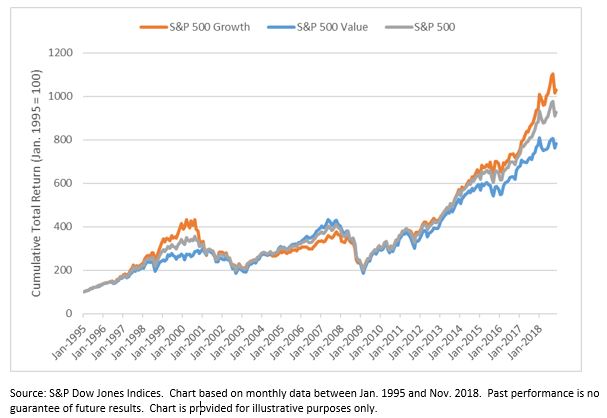

One of the most persistent trends over the last decade has been the underperformance of value compared to growth. The S&P 500 Growth beat its Value counterpart in eight of the last ten full calendar years, and growth is currently on track to outperform in 2018 (you can find year-to-date figures on page four of our daily dashboard).

Exhibit 1: Growth has outperformed over the last decade

Although the trend remains intact so far in 2018, a recent uptick in volatility left many investors wondering if value might be in line for a comeback. Indeed, value outperformed in October and November as many growth-oriented stocks came under pressure from investors looking to take risk off the table. While it remains to be seen if this nascent trend is here to stay, historical sector exposures may be useful for assessing the relative prospects of growth and value.

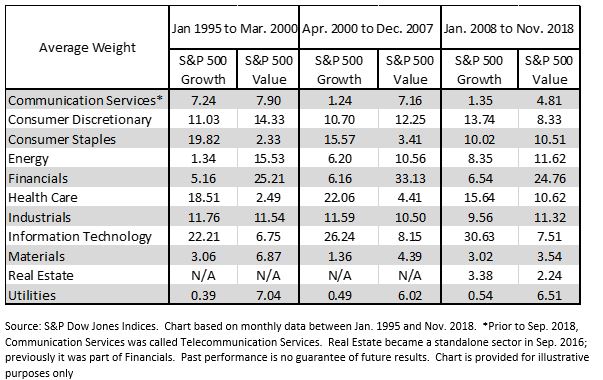

Exhibit 2 shows that Financials and Tech were usually the largest sectors in the value and growth indices, respectively. This result held across all three time frames, capturing 1) the run-up to the height of the Tech bubble (Jan. 1995 to Mar. 2000); 2) the subsequent bursting of that bubble and the run-up to the Global Financial Crisis (Apr. 2000 to Dec. 2007); and 3) the Global Financial Crisis and the most recent bull market in U.S. equities (Jan. 2008 to Nov. 2018).

Exhibit 2: Average Sector Weights in the S&P 500 Value and S&P 500 Growth

Given their large weights in the factor-based indices, it is perhaps unsurprising that the contributions to returns from Financials and Tech were important for understanding the performance of value and growth. For example, Tech contributed most positively to the S&P 500 Growth in the most recent period and in run-up to the height of the Tech Bubble, but it weighed most heavily as the bubble burst. Similarly, Financials was the largest contributor to the S&P 500 Value in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but has been the biggest drag on the value index since the start of 2008.

As a result, there has been much discussion (including in one of our recent videos) about whether the last couple of months represent a style shift in U.S. equities. While it remains to be seen if value is in line for a comeback, history suggests that the (expected) performance of the Tech and Financials sectors could be useful considerations when trying to predict how these styles may perform.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.