In a previous blog, we explored the relationship between corporate governance and stock performance. The results show a wide variance between the top quintile and the bottom quintile, particularly over a long-term horizon (17 years). We applied the same analysis to the RobecoSAM environment (E) and social (S) scores. To do so, we formed hypothetical, annually rebalanced quintile portfolios, ranked by E and S scores, and tracked their forward 12-month performance.i The quintile portfolios were formed on an annual basis as of December 31 of every year.

Looking at the analysis from 2001 through 2017, both E and S scores showed a clear bifurcation in returns, with the bottom quintile performing the worst (see Exhibit 1).

Environment Results

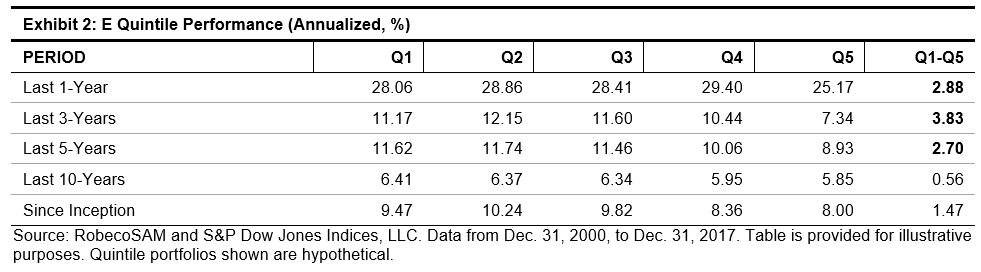

For the portfolios ranked by E score, the fourth quintile (8.36%) and fifth quintile (8.00%) returns were markedly lower than those of the top three quintiles. Over near- to medium-term time horizons, E-ranked portfolios displayed the highest performance spread between the top and bottom quintiles (see Exhibit 2). Perhaps this is because environmental concerns have increasingly moved to the forefront of investor concerns in recent years.

Average rolling returns over the one-, three-, and five-year periods show that, on average, the Q5 portfolio underperformed the Q1 portfolio by about 1.20% (see Exhibit 3).

The results for the governance (G) portfolios showed a greater variance between the top and bottom quintiles compared to the E portfolios. This is expected, as corporate governance reflects management strategy and ability to execute the strategy. On the other hand, E performance reflects risk management of a growing issue that attracts heightened awareness from institutional investors. It appears that for portfolios ranked by E score, market participants may be economically better served by shying away from not only the bottom 20%, but also the fourth-worst quintile, which accounted for the bottom 40% of the ranking universe.

Social Results

The S dimension score measures a corporation’s relationship with its stakeholders, especially its employees, but also the local and wider community in which it operates. The categories analyzed are labor practices, human capital development, talent attraction and retention, human rights stance, and corporate citizenship and philanthropy.

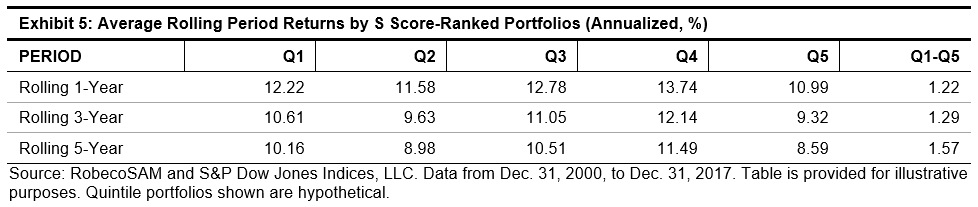

There is a less clear relationship between S scores and subsequent future performance. The back-tested returns do not show a clear underperformance from the bottom quintile, and in fact, the fourth quintile was the best-performing portfolio in the longer time periods (see Exhibits 4 and 5).

Our analysis and the decomposition of the individual ESG scores highlight some interesting information. It appears that for portfolios ranked by G and E scores, investors may be economically better off by screening out securities in the worst quintile of the ranking universe. However, the relationship is less clear between the S score and future stock performance.

The analysis shows that while ranking by overall ESG score could indicate some positive return information, the three underlying subcomponents have different relationships with future stock performance. Therefore, investors may wish to alter the weight of each subcomponent in the overall ESG score.

Our next blog will explore different combinations of the three subcomponent scores.

i The underlying universe is the RobecoSAM coverage universe comprised of global companies starting from December 2000 with 400 stocks and increasing to over 4,000 stocks in 2017.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.