There are only a couple weeks to go until the end of the year, and for a while now, the investing public has seen plenty of material supporting the benefits or risks of diversifying a portfolio through the use of preferred securities. This hybrid type product touts the benefits of high yields, steady income, and a more senior status in the capital structure when compared with common stock.

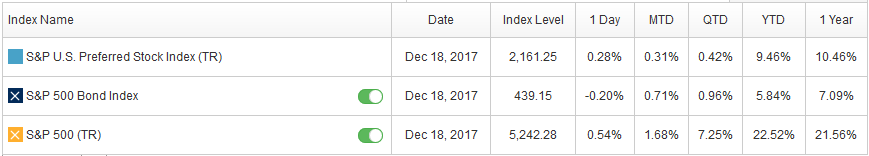

When comparing the asset classes that the preferred hybrid securities sit between, it is noticeable that the preferred class (as measured by the S&P U.S. Preferred Stock Index) has had a higher total return than bonds (as measured by the S&P 500® Bond Index), but not nearly as much as equity (as measured by the S&P 500). What needs to be kept in mind about this is that the volatility of returns as measured by standard deviation is much lower for bonds (0.19) and preferreds (0.21) than it is for equity (0.43). Thus, preferreds tend to be a reliable stream of income that yields more than bonds, but it can also be used as a diversifier since the correlation of returns between bonds and preferreds is low.

Exhibit 1: Preferreds Versus 500 Stocks and 500 Bonds

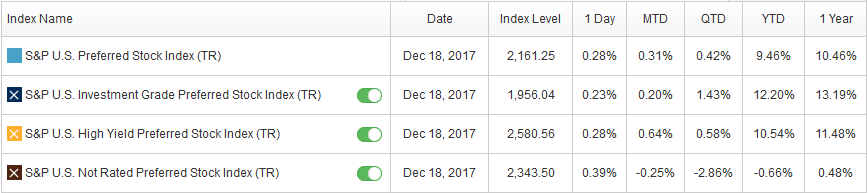

Dissecting the S&P U.S. Preferred Stock Index through the use of subindices can provide exposure to the differing components that make up the parent index. A quick comparison shows that investment-grade preferreds have outperformed high-yield and non-rated preferreds, as well as the parent index.

Exhibit 2: Preferred Ratings Indices Comparison

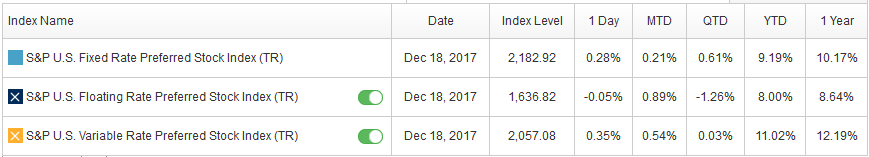

Coupon type can also provide differing exposure, as the S&P U.S. Variable Rate Preferred Stock Index (TR) returned twice the amount of the S&P 500 Bond Index, at 11.02% YTD, as of Dec. 18, 2017. It also helps to know that the S&P U.S. Variable Rate Preferred Stock Index (TR) is made up of 59% high-yield, 28% investment-grade and 12% non-rated securities.

Exhibit 3: Preferred Coupon Indices Comparison

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.