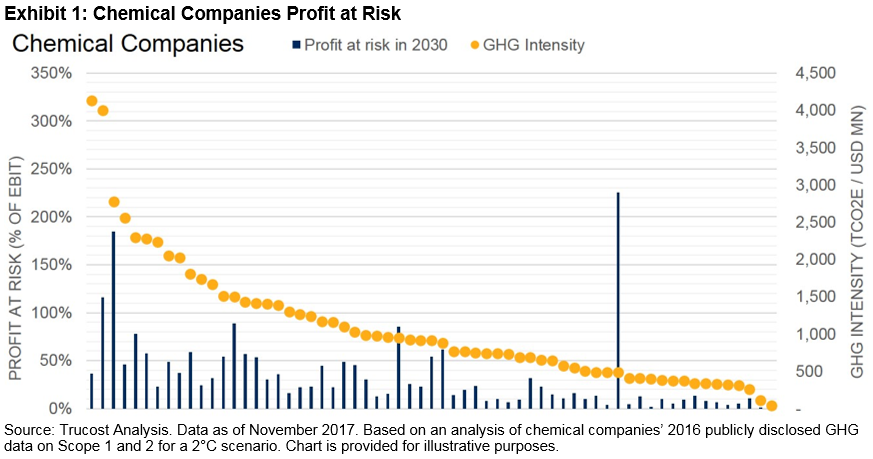

The belief that economic growth is possible without lowering carbon emissions is becoming harder to sell by the minute. A study by the London School of Economics showed that if business-as-usual emissions continue over this century, the value of risk to global financial assets in today’s terms is 1.8%, or USD 2.5 trillion. Likewise, analysis by Trucost shows that operating margins will turn negative for 46% of companies in the chemicals sector by 2030 because emitting carbon will become too expensive (see Exhibit 1).

Clearly, carbon pricing risk—the monetary value that accounts for the future costs of climate change regulation and transition—is likely to be a financially material issue. But addressing carbon risk also creates potential business opportunities.

In August 2017, Trucost launched its Corporate Carbon Pricing Tool to provide a data-led way for companies to translate carbon risk into financial terms. Here’s how carbon pricing can be applied to prove the business case for low-carbon innovation.

- Calculating return on investment (ROI) for low-carbon investments: Sustainability managers need to provide their CFOs with a compelling business case for low-carbon investments. While investment in a diesel fleet versus an electric one may currently have a higher ROI, when factoring in carbon pricing risk, the ROI changes—especially over the lifecycle of the investment. By integrating a risk-adjusted carbon price into investment decisions and showing how future profits are at stake, the business case for low-carbon investment strengthens.

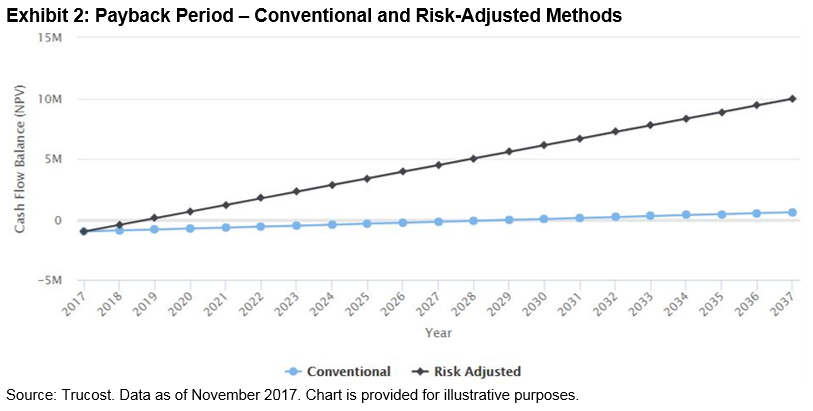

When using the risk-adjusted carbon price, a USD 1 million investment project has a payback period of less than two years and is already providing positive cash flow by the second year, while a conventional payback period would take almost 13 years.

- Informing decision-making: To address carbon pricing, companies will need to either absorb the costs, pass them through to customers, or invest in low-carbon initiatives. To weigh these different options, companies can run their emissions and financial data through the Corporate Carbon Pricing Tool to determine which to prioritize.

- Tailoring investments by region: Some regions have higher carbon pricing risk than others based on current emission schemes. By including this geographic factor, businesses are strategizing how to mitigate the risk, either by relocating their operations to less risky regions or by making low-carbon investments in preferred locations.

- Benchmarking competitiveness against rival firms: Companies are benchmarking against peers to determine how they compare. If a competitor is leading, it may be able to pass fewer costs to consumers and charge lower prices. This directs companies to figure out why peers are more efficient. Is it location alone or because they are investing in energy-efficient technology?

- Engaging individual business units to hit targets: Companies say that by communicating the carbon intensity of specific business units, each unit knows how much it needs to hit its target and contribute to a company’s reduction goal. Not only does this support company-wide engagement, it also helps raise internal funds for pilot projects and investments, like Unilever has done.

- Communicating to investors: Companies increasingly agree that disclosing a carbon price to investors demonstrates a company is taking responsibility for future risks and has the managerial prowess to deliver on climate risk reduction. Increasingly, investors expect companies to report climate-related disclosures by applying scenario analysis, including a 2°C scenario. Additionally, a recent report by S&P Dow Jones Indices showed that low-carbon versions of the S&P 500 and S&P Global 1200 have actually outperformed their benchmarks in the past five years.

Pricing carbon risk provides a strategic link between environmental and financial performance, strengthening the business case for proactively mitigating climate-related risks. Companies and investors that take this step will benefit from a forward lens on carbon risk and the opportunity to inform tomorrow’s low-carbon innovation.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.