As the Dow Jones Industrial Average approaches the 20,000 level everyone seems to be suddenly fascinated with the figure. People who rarely ask if the market is up or down want to know if the Dow will cross this supposed benchmark today. Journalists with years sent covering the markets want to know what 20,000 means. But, if the Dow had started in 1895 instead of 1896 we would probably have passed 20,000 a year ago.

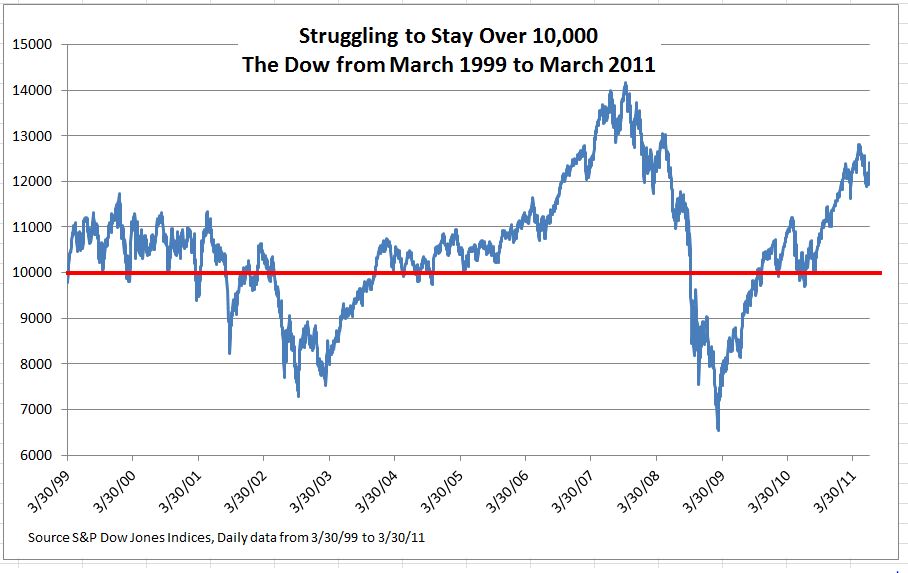

Before we all get too excited, we might remember what happened after the Dow crossed 10,000 for the first time in April, 1999 – it took two big falls back over the next 10 years. The chart shows the Dow from March 30, 1999 to June 30, 2011 with two nasty bear markets.

Psychological studies suggest that a round number is seen as more stable and solid than a more precise figure. Saying the Dow closed 9,911.21 yesterday may be sound precise and accurate but certainly doesn’t hint have the positive attributes that people tend to associate with a large round number. If you ignore the chart 20,000 might make you think the market isn’t about to drop. Round numbers may be used to describe products while more exact numbers slightly below a round number are popular for prices. Prices of individual stocks tend to cluster near round numbers, probably because most people read numbers left to right and 19.90 sounds a lot cheaper than 20.00. An investor will buy at 19.90 but hold at 20. Moreover, the scale matters: when markets in Europe switched to the euro from the former local currencies, these round number effects switched from the local currency to the euro.

For investors the level of the Dow or any index depends on an arbitrary base value — what really matters the percentage gain or loss over time.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.