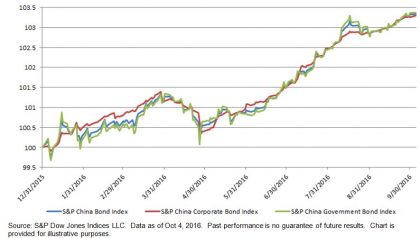

The performance of China’s fixed income market has lagged other Asian countries this year. According to the S&P China Bond Index, the fixed income market delivered a YTD total return of 3.57% as of Oct. 11, 2016. China was one of the top three outperforming countries in the S&P Pan Asia Bond Index last year; the other two countries measured by the index, Indonesia and India, increased 17% and 9% YTD, respectively. Despite China opening up its bond market to offshore market participants, the country still underperformed, and in February there was a short rally following the Chinese Interbank Bond Market (CIMB) announcement, yet the gain was reversed in April.

The size of China’s bond market has continued to expand nevertheless. The market value tracked by the index reached CNY 48 trillion, whereas corporate bonds represented 34% of the overall market.

The yield of Chinese bonds trended lower, aligning with the global market. The yield-to-worst of the S&P China Bond Index tightened 17 bps to 2.93% YTD. The yields of the government and corporate bonds were 2.73% and 3.34% respectively. Among all the sector-level subindices, the S&P China Industrials Bond Index had the highest yield, at 3.56%.

The S&P China Bond Index is designed to track the performance of local-currency-denominated bonds from China. S&P Dow Jones Indices has launched both broad-based and investible indices of the S&P China Bond Index Series.

Exhibit 1: Total Return Performance of the S&P China Bond Index, S&P China Government Bond Index, and the S&P China Corporate Bond Index