If early January is any indication, 2016 should be another year when low volatility strategies will be in vogue. Popularized in the turmoil following the financial crisis in 2008, low volatility strategies, as the name denotes, serve well in times of equity upheaval. And despite bearing lower risk low volatility strategies have outperformed their benchmarks over time. The S&P 500 Low Volatility Index is an example of such a strategy. In the 25-year period ended in December 2015, Low Vol delivered an average annual return of 10.91% compared to 9.82% for the S&P 500 with less volatility (standard deviations of 11.04% and 14.44%, respectively). Year to date, Low Vol is outperforming the S&P 500 by approximately three percentage points.

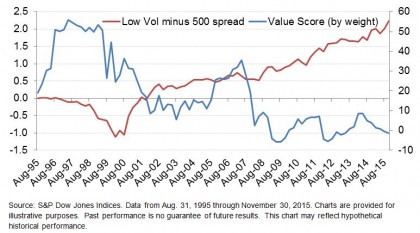

However, as with any investment consideration, it’s prudent to look at a few fundamentals as a gauge of whether timing is opportune. Is it possible to isolate windows for which an entry point into Low Vol will offer most bang for the buck? To address this question, we look at the current S&P DJI Style model which utilizes book/price, sales/price, and earnings/price as value components. In the graph below, the red line (left axis) charts the performance spread between the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index and the S&P 500. The blue line (right axis) charts the value score of the low volatility index over time. Value scores are constructed relative to the overall market. By design, the S&P 500 has an average value score of 0. A positive value score reflects cheapness relative to the S&P 500. Conspicuously, Low Vol’s current value score has been hovering near all-time lows. If value is relevant, now would be an inauspicious time to get into Low Vol.

But, looking at history, Low Vol notched its highest value score (valuation was cheapest) in 1997 close to the onset of the technology bubble. Entry into Low Vol at that point would be followed by years of underperformance that would last through 2000. In contrast, one of the most expensive points of Low Vol was in the months following the financial crisis. That wasn’t too long ago but the red line in the chart above does a very good job illustrating what’s happened to Low Vol since then. As a timing indicator, at least for Low Vol, value is not very valuable.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.