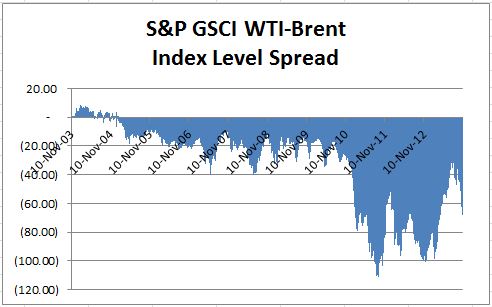

2014 is just around the corner now and the new weights for both the DJ-UBS CI and S&P GSCI have been announced. While the index weightings follow the methodologies, there are questions around the weights of two particular commodities, Brent crude oil and WTI crude oil. The interest comes from the fact that they are the most heavily weighted commodities across the two indices and there has historically been a popular spread trade between the two, since theoretically they should trade similarly given their qualities. However in the past few years, there has been a build-up of WTI from the recent surge in US production, causing the price differential to increase where Brent has been more expensive than WTI.

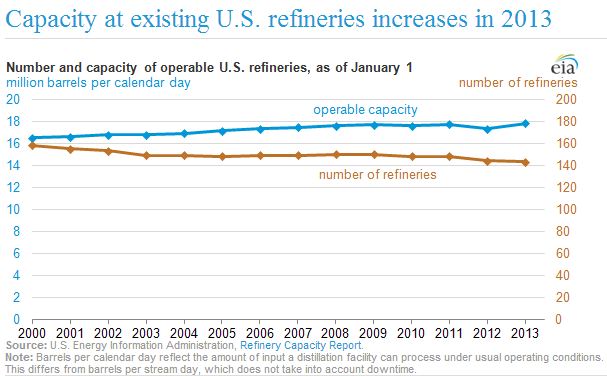

In 2013, the WTI- Brent spread narrowed from improving transportation and increased midstream infrastructure to enable crude to be transported to coastal refiners. Also, according to the EIA, refiners have been running at higher rates, driving up the demand for WTI.

The WTI-Brent spread has historically traded near par and reached near par at points earlier this year. However, given the structural change of significantly more oil being produced from the U.S. (with projections of continued future growth), many market participants expect Brent to be priced at a premium to WTI. For example, the EIA, noted in its monthly report titled “Short Term Energy Outlook” that it expects a spread of ~$6 per barrel in 2014. They also noted that the Brent-WTI price spread may be influenced by the balance between future growth in U.S. crude production and the capacity of crude oil infrastructure to move that crude to U.S. refiners.

So, the question is, why are the 2014 target weights in the DJ-UBS CI and S&P GSCI for WTI still heavier than for Brent?

Simply stated, the reason WTI is still heavier than Brent is because the data used to calculate the weights is based on historical five year averages. Both indices use world production and liquidity in the weighting calculations, though the factors are applied in a slightly different way for each index.

For example, in order to construct the weights of the commodities in the DJ-UBS, a ratio of 2:1 of liquidity: production is applied. The liquidity is a based on annual volume data for the five years up to and including the year prior to the calculation period. For example, the target index weights in 2014, which are calculated in 2013, include years 2008-2012.

For each commodity, a relative liquidity is assigned by taking the ratio of the individual contract liquidity versus the total index liquidity. The production also uses a 5 year average of US dollar adjusted production based on the latest common date of production across all commodities. The 2014 index weights are calculated in 2013, so the data spans from 2006-2010. The weighting process then adjusts the data into similar units as in the futures contracts (like barrels for oil). Finally the average settlement prices for the first day of every month are converted into US dollars and multiplied by production. The relative production, like relative liquidity is the result divided by the overall index production. Finally, limits are enforced so that no single commodity is over 15%, no derivative commodities (like Brent, WTI, Heating Oil and Unleaded Gasoline) are greater than 25% combined, and no group (Energy) is greater than 33%.

The S&P GSCI uses a similar methodology for data collection, though the application for weights is slightly different that results in dramatically different target index weights than for the DJ-UBS CI, especially since there are no weight limits for the S&P GSCI. The S&P GSCI applies a relative world production weight to each component (a component may be more than one commodity: for example, petroleum includes Brent, WTI, Gasoil, Heating Oil and Unleaded Gasoline.) There are 18 components in the S&P GSCI that are constructed from 24 individual commodities. After the relative world production is calculated, a relative liquidity adjustment is applied that drives the weighting difference between commodities of the same component, like WTI and Brent.

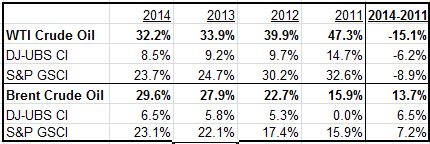

The resulting impact on the indices has been a weight that is shifting out of WTI and into Brent, though Brent has not taken over WTI yet. Please see the chart below for the historical weightings since Brent was added into the DJ-UBS CI.

The next common question is what impact will this have on the market?

Fortunately or unfortunately, this question is not as predictable as the former question. By estimated assets tracking published for year end 2012, which were approximately $75 billion for the DJ-UBS CI family and approximately $80 billion for the S&P GSCI family, that implies (given all else constant) from the 2011 rebalance through the 2014 rebalance, a total of about $23.4 billion is removed from WTI and about $21.2 billion is placed into Brent, where roughly $2.6 billion is set to move during the 2014 rebalance.

Finally, does this mean Brent will increase in price and WTI will drop?

If we look at the 2013 rebalance period (Jan 8-14, 2013 for the S&P GSCI, and Jan 9-15, 2013 for the DJ-UBS CI) for some guidance, we notice that approximately $9.3 billion flowed out of WTI and $8.1 billion into Brent based on estimated assets tracking the flagship indices, DJ-UBS CI and S&P GSCI. However, due to the expansion of the Seaway Pipeline in January 2013 to enable more WTI to flow from Cushing in Oklahoma to the Gulf Coast refiners, the S&P GSCI (WTI) Crude Oil increased 57 basis points over the rebalance period when assets tracking flowed out. At the same time the S&P GSCI Brent experienced a 1.39% loss despite the inflows.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.