Beyond the growth in nominal GDP, the other two macro-factors that may influence the returns of the S&P 500® Dividends Index: payout ratios and corporate earnings.

When corporations make profits, they have a choice: They can either reward shareholders or they can retain and reinvest the earnings. While some companies, notably fast-growing technology firms, opt to retain all of their earnings, most choose to pay out a portion in dividends. These dividend payout ratios fluctuate over time, though not necessarily with a strong correlation to the economic cycle. Payout ratios rose during the 1980s boom but declined during the period of strong growth during the 1990s. They also fell substantially during the 2008 recession, but rose during the most recent expansion. Dividend payout ratios can also fluctuate in response to changes in tax policy. Over the past few decades, payout ratios have averaged to around 40-50%.

Corporate Earnings

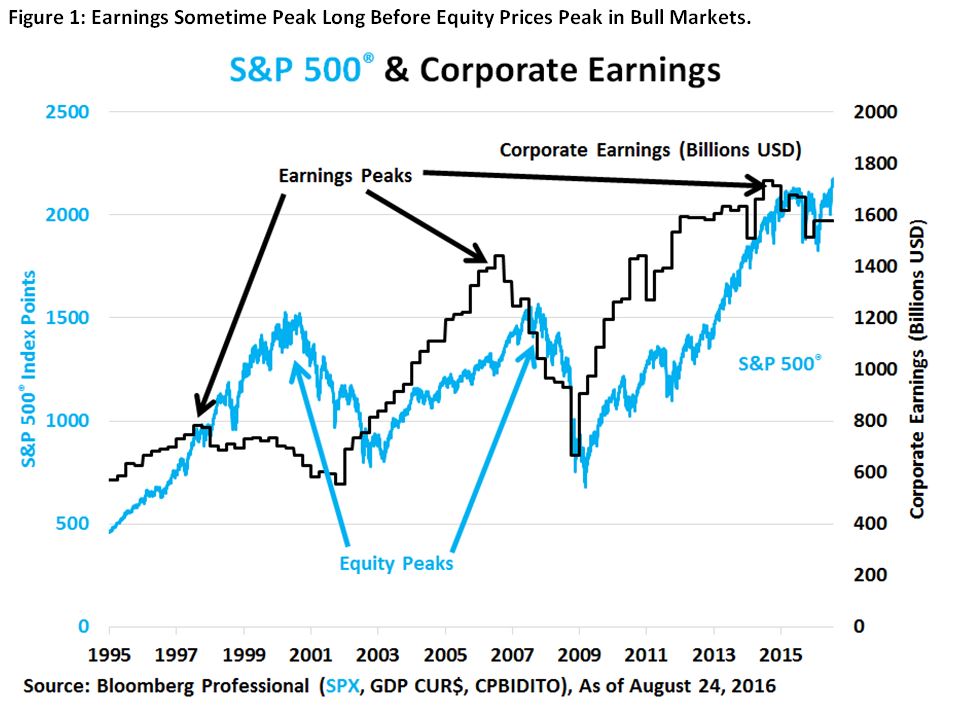

Corporate earnings rarely exceed 10% of GDP. They reached this level briefly in 2006 and hovered around 10% from 2011 to 2014. They have since dropped to around 8.5% because the labor market has tightened, wages have begun to rise while productivity growth has remained slow. All of these factors are putting downward pressure on corporate profits. The impact of declining corporate profits on dividends has been offset by two other factors:

- Continued growth in nominal GDP, which has been growing at around 3.5% year on year.

- A rising dividend payout ratio, which now exceeds 50% of earnings.

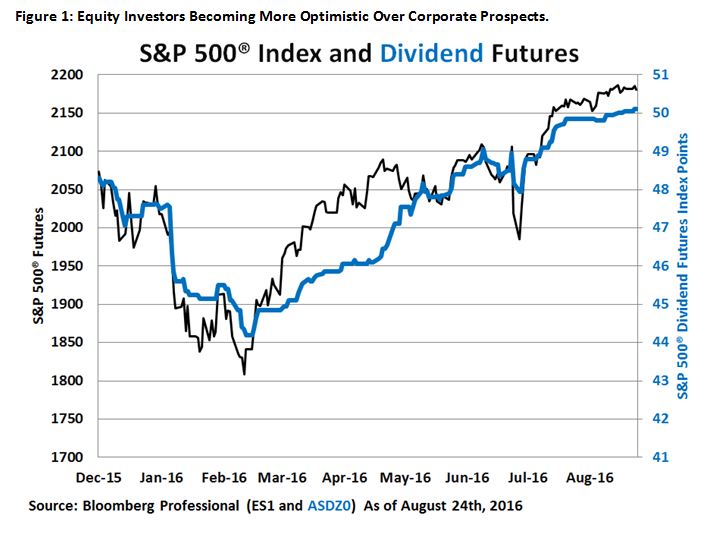

Notably, when corporate earnings peak as a percentage of GDP and begin to decline, equity prices can continue to rise. During the 1990s, earnings peaked as a percentage of GDP in 1997 while stocks continued to rise until 2000. During the subsequent decade, earnings peaked relative to GDP in 2006 but stocks didn’t reach their highest levels until late 2007. Likewise, this time around, earnings as a percentage of GDP may have plateaued in 2011-14 and then began falling, but the S&P 500® continued upward and broke to a new record high (Figure 1). As such, a peak in earnings doesn’t necessarily imply an imminent peak in equity prices. That said, post-peak earnings declines often correlate with periods of rising equity volatility (Figure 2).