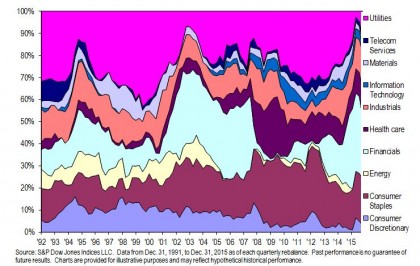

Different sectors within the same country can perform differently. Not all sectors of the economy perform well during a bull market and vice versa. Hence, an investment fund heavily focused on one or two sectors could be more volatile and susceptible to a single market incident or regulatory measure. In addition, no particular sector can shine in all economic climates and will have ups and downs during different periods. To attempt to reduce volatility caused by this sector movement, an investment fund (tracking a single country in particular) could track an index with a more diversified sector allocation.

Chinese Equity Indices Concentrate on the Financial Sector

When we take a closer look at some key Chinese indices which track the Chinese equity market, we see that they tend to have a high allocation to the financial sector, some even more than 50%. In fact, many Chinese financial companies are massive, and some of them are state-owned enterprises supported by the government. They tend to have large market capitalization and are liquid, enabling them to pass the market-cap and liquidity screens required by the Chinese indices, therefore making them eligible for index inclusion.

However, the Chinese indices selecting the largest stocks tend to overweight the financial sector but underweight other growing sectors that do not have a high market cap. In order to give an accurate representation of the broad Chinese equity market, an index should be more diversified across different sectors.

The S&P China 500 Enhances Sector Diversification

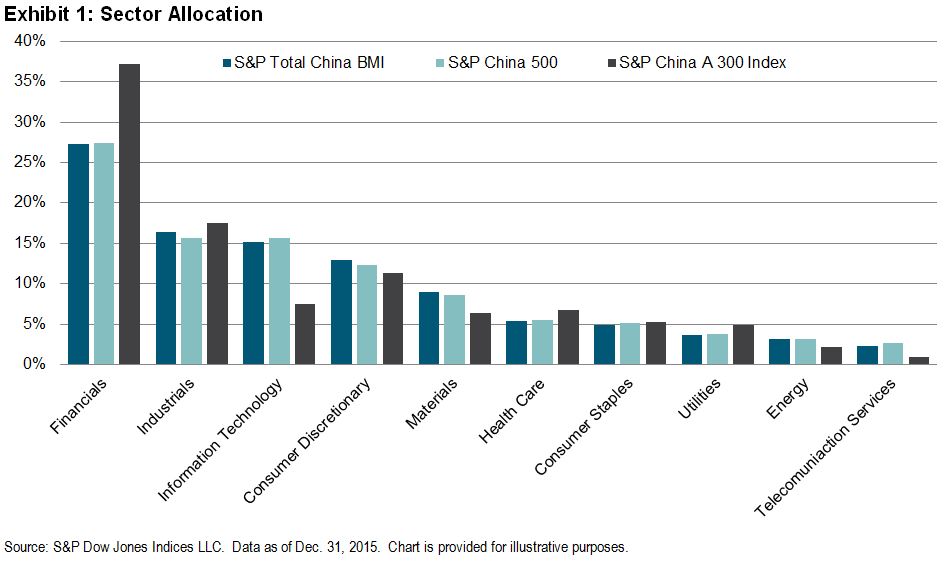

To approximate the sector composition of the broader Chinese equity market, the S&P China 500 has a unique constituent selection criteria. This index compares and matches the sector breakdowns of selected stocks in the S&P Total China BMI, which consists of about 3,000 constituents and represents the entire investable universe of Chinese companies. The S&P China 500 is less concentrated in the financial sector compared with other key China indices (such as the S&P China A 300 Index) and closely matches the sector weights of the broad Chinese equity market, as represented by the S&P Total China BMI (see Exhibit 1).

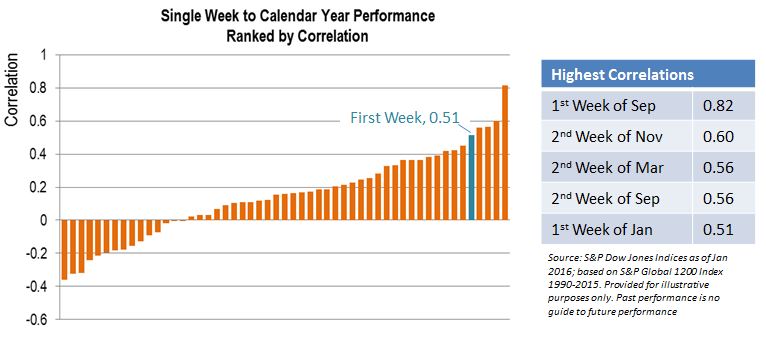

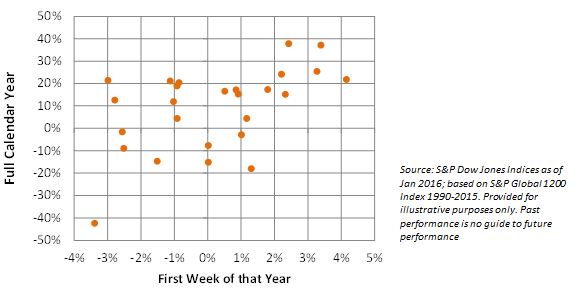

Not all weeks are equally important

Not all weeks are equally important