The S&P 500® Dividend Aristocrats® is an index comprising companies in the S&P 500 that have increased their annual cash payments for at least 25 years in a row. Dividends are a part of their culture and public appeal (income), as they broadly highlight their increases. In general, their increases are smaller but still constant, and even in bearish markets, these companies have continued to increase (for example, the 2000-2002 Tech Bust, the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis, and most recently during the COVID-19 pandemic).

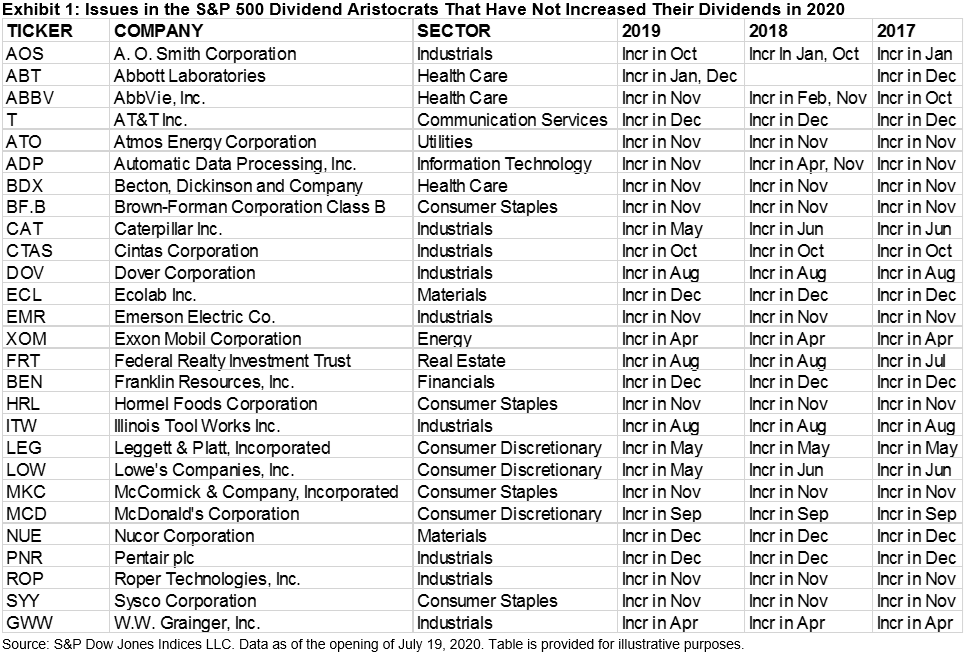

As of July 19, 2020, there were 65 issues in the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats, including the spun-off issues of Carrier and Otis (from United Technologies, which is now Raytheon) and after the removal of Ross Stores. Of the 65, 33 have already increased dividends, and both spin-offs have started to pay them. One issue, Ross Stores, suspended its dividend and was therefore removed before the market opening of July 1, 2020.

Because of the timing of the dividend increases, if none of the current issues were to change their dividend rate (no increases and no decreases) for the remainder of the year, all but one would pay more in 2020 than they did in 2019, an important requirement for membership in the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats. Some of the companies would have a “bye” in 2020, a sports term referring to when a team advances even though they did not compete in a match in that round.

Consider a company that paid quarterly dividends of USD 0.50, USD 0.50, USD 0.60, and USD 0.60 in 2019, and then paid four dividends of USD 0.60 in 2020; without an increase, the 2020 payment would be higher than that of 2019. Under this scenario, 28 issues would have a bye year and need to increase their actual payment rate in 2021 (“byes” are not common, with the last one being United Technologies in 2019, before its spin-off; Chevron in 2017; and Caterpillar in 2016). The sole company (at this time) that would not increase its dividend in 2020 over that of 2019 is VF Corporation, which, at its current rate, would pay USD 1.92 for 2020, compared with USD 1.93 in 2019 (through year-end 2019, it had increased dividends for 47 consecutive years).

The working base case for the Dividend Aristocrats is that they will pay through 2020, with some utilizing the “bye” feature. Of note (to the “bye” feature) are ExxonMobil and W.W. Grainger, which typically increase in April but did not this year, and Leggett & Platt and Lowe’s, which typically increase in May but did not. July 2020 has already produced traditional increases from PPG Industries, Stanley Black & Decker, and Walgreens Boots Alliance. August typically brings increases from Dover Corporation, Federal Realty Investment Trust, and Illinois Tool Works—but even if they did not increase, at their current rate, they will pay more in 2020 than they paid in 2019.

The bottom line for the Dividend Aristocrats appears to be that they will pay through Q3 2020, and absent a downturn (cash flow), they will also pay through Q4 2020. The number of increases may drop (use of the “bye”), and increases may be smaller than usual (with increases of one penny being the new wink). However, a small increase in their dividends would be preferable to those 62 issues in the S&P 500 that have cut since mid-March 2020.