Black Swans and Green Elephants: Time Inconsistency, Salience, and the Tragedy of the Horizon

“When the well is dry, we know the worth of water.”[1] These were Benjamin Franklin’s cautionary words over 250 years ago. March 22, 2018, is World Water Day, and this year the residents of Cape Town will be feeling the poignancy of his words as they approach “Day Zero”—the day the taps will be turned off (July 9, 2018). Their three-year drought has caused households and businesses to take radical measures to reduce water consumption.[2] Cape Town will not be alone, as the UN warns that by 2030, global demand for fresh water will exceed supply by 40%.[3]

Franklin’s words remain as true today as they were then, because we humans are irrational in how we quantify value and risk at different points in time. This is evidenced by behavioral finance experiments in which it was observed that losing something makes us approximately twice as miserable as gaining the same thing makes us happy.[4] However, preserving what we have is also subject to biases, as we tend to undervalue future risks, particularly if there is a short-term “cost.” Humans are prone to temptation, procrastination, and status quo bias, which explains why so many New Year’s resolutions are broken and why vices such as smoking and drinking remain prevalent, despite our knowledge of the negative consequences.

The interplay of value, risk, and time inconsistency presents a problem for the pension industry. Behavioral factors need to be addressed to encourage people to save more for their retirement, and the investment industry itself needs to tackle the structural and behavioral causes of short-termism. Myopic assessments of risk/reward drove the “irrational exuberance” at the heart of many financial bubbles, and they are a key reason why 50% of investors do not take environmental issues into account.[5] Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, calls this “The Tragedy of the Horizon,”[6] which also alludes to the “Tragedy of the Commons,” a term used in environmental economics to describe the inefficient use of seemingly “free” natural resources. Climate change and resource depletion have short-term financial impacts, too—as the tourism and agriculture industries in Cape Town can attest to—but these will intensify and accelerate over time. In order to mitigate the worst impacts, we need efficient allocation of capital that accurately weighs up short-term costs with long-term benefits. The rational man of classical economics would have no problem with this exponential discounting, but human deviation from rationality leads to environmental externalities, misallocation of resources, and market failure. A good example of the latter is water, where the market price is inversely correlated with its scarcity (see Exhibit 1).

Market failures are not our only challenge; the relatively short-term focus of financial models can cause blind spots for investors. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recently argued that modern portfolio theory is inadequate for incorporating ESG issues because it supports short-termism, is not forward looking, and leads to herding.[7]. It also argues it is ill equipped for the types of discontinuous risk associated with climate change. As the NGO the 2 Degrees Investing Initiative eloquently put it, “All swans are black in the dark.”[8] We must also remember that climate impacts will accelerate, so the future will not look like the past, and as Carney states, “The past is not prologue and the catastrophic norms of the future can be seen in the tail risks of today.”[6] This presents particular problems for new funds trying to break the status quo bias and take a forward view on environmental issues, because back-tests are often used to judge their potential future performance.

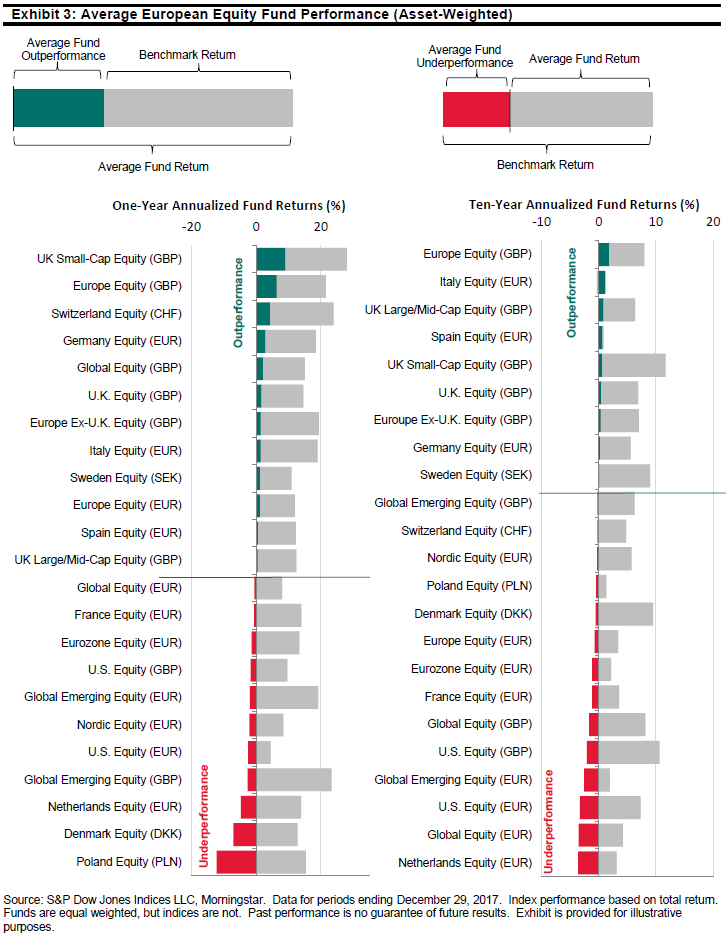

Salience can make a difference. If an event is recent and emotive, it is easier to recall, and there is a higher probability of it occurring again. In Cape Town right now, the financial and human impact of water shortages will be particularly salient, but let us hope that we do not have to wait for further catastrophic climate events to make us take the true cost of environmental issues into account. As we enter a new era of lower-carbon, more resource-constrained economic development, we would be wise to remember the disclaimer, “past performance is no guarantee of future results.”

If you liked this blog, you may also like part 1, “‘Nudging’ Sustainable Finance Into the Mainstream: How Behavioral Finance Could Transform Capital Flows to ESG,” and part 2, “The Big Green Elephant in the Room: Why Do We Assume That “Green” Investing Means Sacrificing Returns?”

[1] Benjamin Franklin (1746), “Poor Richard’s Almanac.”

[2] Curnier, Benjamin, The Economist Intelligence Unit, (Feb. 28, 2018), “Cape Town’s water crisis shows the reality for cities on the front line of climate change.”

[3] UN World Water Development Report 2015, (2015), Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

[4] Thaler, Richard and Cass Sunstein (2009), “Nudge.” Yale University Press.

[5] The CFA Institute (2017), “ESG Survey 2017.”

[6] Carney, Mark, (Sept. 29, 2015), “Mark Carney: Breaking the tragedy of the horizon – climate change and financial stability”

[7] OECD (2017), “Investment governance and the integration of environmental, social and governance factors.”

[8] 2 Degrees Investing Initiative and the Generation Foundation (February 2017) “All Swans are Black in the Dark: How the Short-Term Focus of Financial Analysis Does not Shed Light on Long Term Risks.”

If you enjoyed this content, join us for our Seminar Discover the ESG Advantage in

London on May 17, 2018.