Earlier this week, the Wall Street Journal featured a long article arguing that Morningstar’s star ratings for mutual funds were a “mirage.” Since these ratings exert a powerful influence over fund flows, their usefulness is obviously of keen interest to investors. To its credit, Morningstar, although arguing that its ratings are a “worthwhile starting point,” acknowledges that they are backward-looking and were not designed to be a predictive model of future performance. Morningstar’s own analysis argues that the ratings are most powerful when used to select allocation or taxable-bond funds, while they “exhibit less predictive power” for U.S. equities.

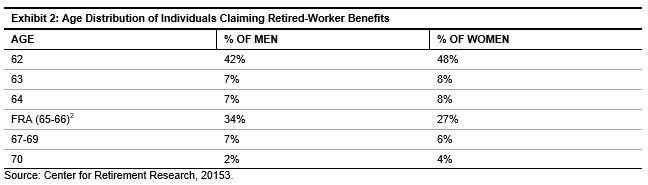

This will not surprise anyone who has even a nodding acquaintance with our Persistence Scorecards. A companion to our better-known SPIVA reports, our Persistence analysis asks whether managers’ historical success predicts their future results. Looking back ten years, e.g., we can ask whether top quartile managers in the first five years repeated their performance in the second five years. As the table below shows, they typically don’t:

If performance were random, 25% of the top quartile managers from the first five years would be in the same quartile in the second five years. In fact, across the cap range, top quartile managers were more likely to move to the bottom quartile than to remain at the top.

Ironically in view of this week’s controversy, a valuable perspective on the same phenomenon comes from a 2010 Morningstar study. The study examined the predictive power of star ratings and expense ratios, and noted that “If there’s anything in the whole world of mutual funds that you can take to the bank, it’s that expense ratios help you make a better decision….In every asset class over every time period, the cheapest quintile produced higher total returns than the most expensive quintile.” If low expense ratios are predictive of returns, it follows that “you get what you pay for” is wrong, at least in a general sense. If you got what you paid for, high-expense ratio funds would outperform low-expense ratio funds. If you don’t, that’s a powerful argument in favor of the kind of mean reversion we persistently see in our Persistence Scorecards.

Given the burden of empirical evidence, one is left to wonder why investors continue to include past performance as a factor in their decision making. I suspect that it’s deeply and fundamentally behavioral – we human beings are conditioned to believe that the past predicts the future. And in much of life, the past is a useful guide. Because investment management is an exception, not the rule, confusion about the importance of historical performance is likely to continue.

The posts on this blog are opinions, not advice. Please read our Disclaimers.